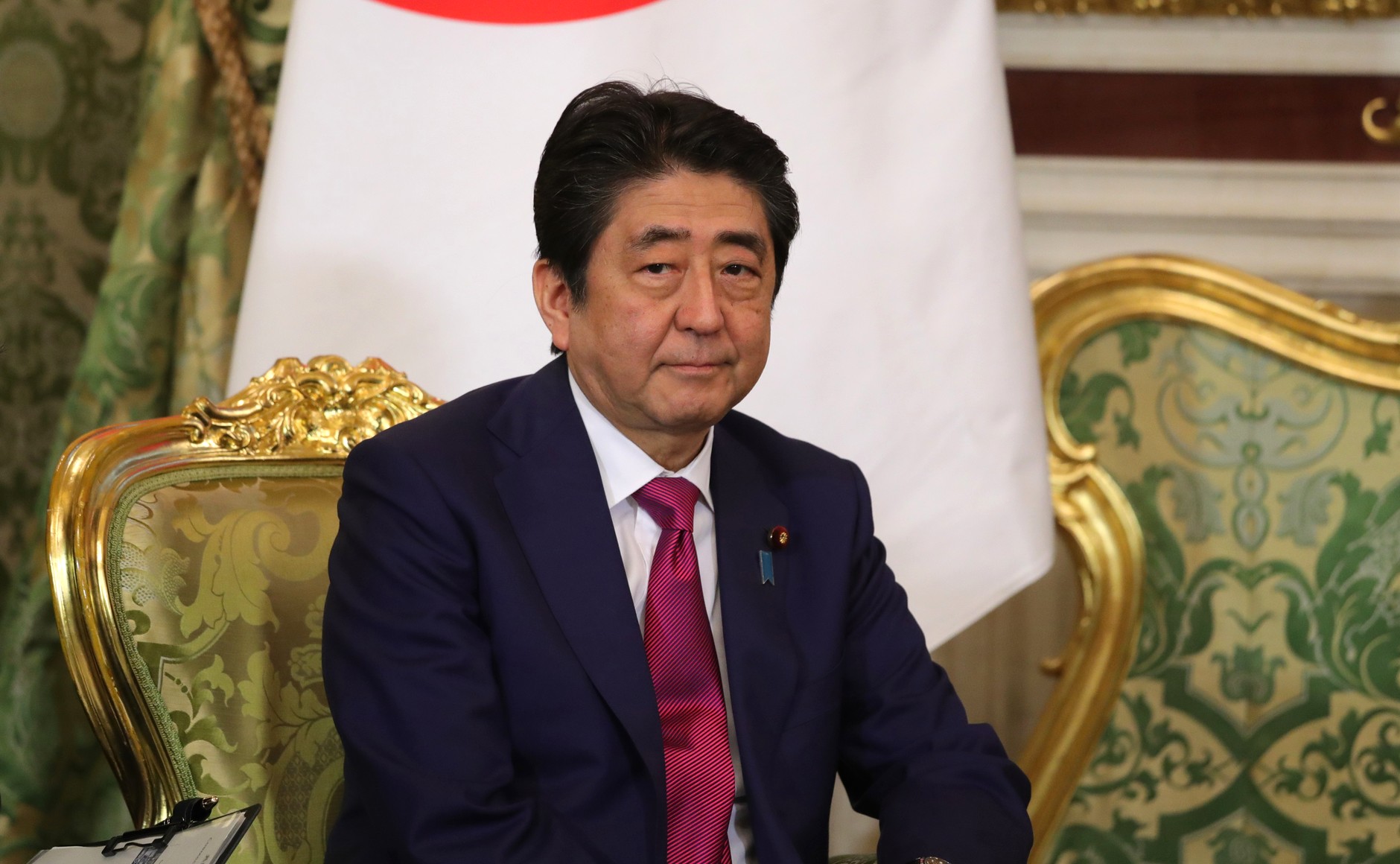

The G20 Summit and Shinzo Abe’s accompanying tour around Europe should have been a landmark event for the Prime Minister. With the EU-Japan trade deal being signed in time for the summit, Abe arrived as a champion of free trade and the liberal order – positioning Japan and his government as a beacon of stability in turbulent times. Yet all his success on the international stage could not change events at home; Abe was forced to cut short his trip to return to Japan and face a sharply declining domestic political situation.

This week’s opinion polling, coming on the heels of the LDP’s dramatic collapse in the Tokyo Assembly elections, are among the most negative the Prime Minister has faced since his return to power in 2012. Opinion polls in Japan often diverge widely depending on which media organisation conducts them, but on this occasion their findings align; the cabinet’s approval ratings have collapsed since May, and now hover in the low-to-mid 30s. Even the Yomiuri Shimbun’s polling, which has consistently favoured the LDP government and showed a 61 percent support rate back in May, now shows only 36 percent support.

Commentary on the cabinet’s declining support rate has focused on its likely impact on two areas – the longevity of Abe’s tenure, which had formerly been expected to extend through 2020, and the likelihood of his achieving arguably his most cherished long-term goal, the revision of the Japanese constitution. Both of these, according to the now-prevailing conventional wisdom, have been thrown into significant doubt; yet in reality, the Prime Minister’s position within the LDP remains secure, even if his political capital has been diminished.

It’s true that Abe appears to have crossed the line from being an electoral asset to being a liability. Detailed polling shows that the slump in cabinet support has been accompanied, and likely fuelled by, a significant decline in the Prime Minister’s personal standing among voters. Indeed, many of the LDP’s current difficulties are related to Abe himself, directly or indirectly. Since 2012, his governing style as Prime Minister has gradually become more and more presidential; he has surrounded himself with personal allies, centralized power and influence in the Prime Minister’s office and replaced the already-crumbling edifice of Japan’s corporatist bargaining structure with something more akin to influence-peddling.

Much of this has now come back to bite him. Favors granted to Abe’s ideological and personal comrades have resulted in a pair of long-running scandals in the form of the Moritomo Gakuen and Kake Gakuen, with the LDP’s high-handed and dismissive treatment of these issues seemingly only fuelling the fires of public suspicion. His high valuation of personal loyalty, and his willingness to reward those who demonstrate it, has left him saddled with low quality or even utterly disastrous “friends” in positions of power. Chief among them is Defence Minister Tomomi Inada, whose survival in her position despite repeated gaffes and a clear lack of competence can only be attributed to the Prime Minister’s patronage. Inada is not alone; Abe’s last cabinet reshuffle raised eyebrows when it seemed to largely ignore the LDP’s tradition of balancing representation between the party’s internal factions in favor of handing out key positions to Abe’s personal allies. Even in the midst of his own influence-peddling scandals, the Prime Minister has been reported to favor a return to the cabinet for Akira Amari, who was forced to resign from his ministerial post in 2016 due to bribery allegations.

Settling individual scandals won’t change the whiff of corruption and cronyism that many voters now sense about the Prime Minister

Taken individually, these issues are survivable; they are all arguably rather minor as scandals go. Nothing was ever conclusively proven about Moritomo Gakuen (though its principal, Yasunori Kagoike, remains a stubborn thorn in Abe’s side; hell hath no fury like an ultra-nationalist scorned, apparently), and the Kake Gakuen issue will likely be put to bed with a round of apologies and promises to “reflect.” Inada will be shuffled out of the cabinet this summer and Amari, who might have made a reappearance in better times for the LDP, will probably stay in obscurity a while longer.

Settling each individual scandal, though, won’t change the whiff of corruption and cronyism that many voters now seem to sense about this government and its Prime Minister. Time and some policy successes will heal much, but Abe has lost a great deal of political capital over these issues, and his image of electoral impregnability suffered a devastating blow in Tokyo. His ratings will recover, but it’s unlikely he’ll ever restore the glow of popularity he had before the events of recent months.

Abe’s critics and opponents should not raise their hopes, however. The Prime Minister’s position remains far more secure than the negativity currently surrounding him might suggest. True, the LDP has a history of defenestrating prime ministers whose approval rating drops sharply, but that was a very different time for the party, before Koizumi and Abe hollowed out the LDP’s internal competition and began its transformation into a more centralized, top-down kind of organisation. Factional politics still matters, and some smaller factions would prefer new leadership – but this must be balanced against the rising importance of loyalty to the leadership. Shigeru Ishiba has positioned himself as Abe’s primary rival within the LDP, but even as Abe’s popularity has dimmed, Ishiba’s star has not ascended; his support is thin and far from vocal. Fumio Kishida, the current Foreign Minister, is by far the most likely successor to Abe; he reportedly wishes to leave the cabinet and take on a senior party role in the upcoming reshuffle, which would confirm his leadership ambitions. However, he has largely been careful to position himself as a loyal cabinet member whose ambition is to succeed Abe, not to challenge him.

Nobody in the LDP is positioned to challenge Abe, and no opposition party threatens the LDP nationally

Abe’s position may be more precarious now, but in the absence of a significant challenger (either within the party or without), by far the most likely scenario remains his continuation as Prime Minister until he chooses to step down. It’s now a little more likely that he will step down before 2020, perhaps choosing not to serve another term as LDP president; the Prime Minister’s health, which forced him from office back in 2007, is a wildcard in this scenario that has been mentioned often in the media in recent weeks.

If he is truly determined to weather this storm, however, he will – there’s nobody in the LDP with a support base that can challenge his, and no opposition party seriously threatens the LDP on the national stage. Abe will make his choice with one eye on the issue of his legacy; he would view leaving office before achieving some revision of the constitution as an enormous defeat, and would also likely prefer to be the Prime Minister when the world’s eyes turn to Japan for the 2020 Olympic Games. Absent any more major scandals embroiling the Prime Minister, both of those things remain possible – and even more so if his summer reshuffle suggests that he’s learned to value competence over loyalty in his cabinet picks.

Read more:

New polls show support for Abe eroding :: Tobias Harris, Sasakawa USA

LDP anxious over drop in ratings :: Yomiuri Shimbun

Abe Considers Reshuffle; Foreign Minister Kishida Intends to Step Down :: Kyodo [Japanese]

Kagoike requests investigative Osaka assembly panel over school plan :: Japan Times

Rob Fahey is an Assistant Professor at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study (WIAS) in Tokyo, and an Adjunct Professor at Aoyama Gakuin University's School of International Politics, Economics, and Communication. He was formerly a Visiting Professor at the University of Milan's School of Social and Political Sciences, and a Research Associate at the Waseda Institute for Political Economy (WINPEC). His research focuses on populism and polarisation, the impact of conspiracy theory beliefs on political behaviour, domestic Japanese politics, and the use of text mining and network analysis techniques for political and social analysis. He received his Masters and Ph.D from Waseda University, and his undergraduate degree from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.