Revising Japan’s post-war constitution has been a goal of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party for decades, but for most of that time it’s been more a question of posture and positioning than of concrete policy. LDP grandees might make public noises of discontent regarding the American-drafted document and its restrictions on state power, but for most of its history the LDP has remained in government by merit of being far more pragmatic than ideological in nature, and the Constitution has been enormously popular with the Japanese people for much of the post-war era.

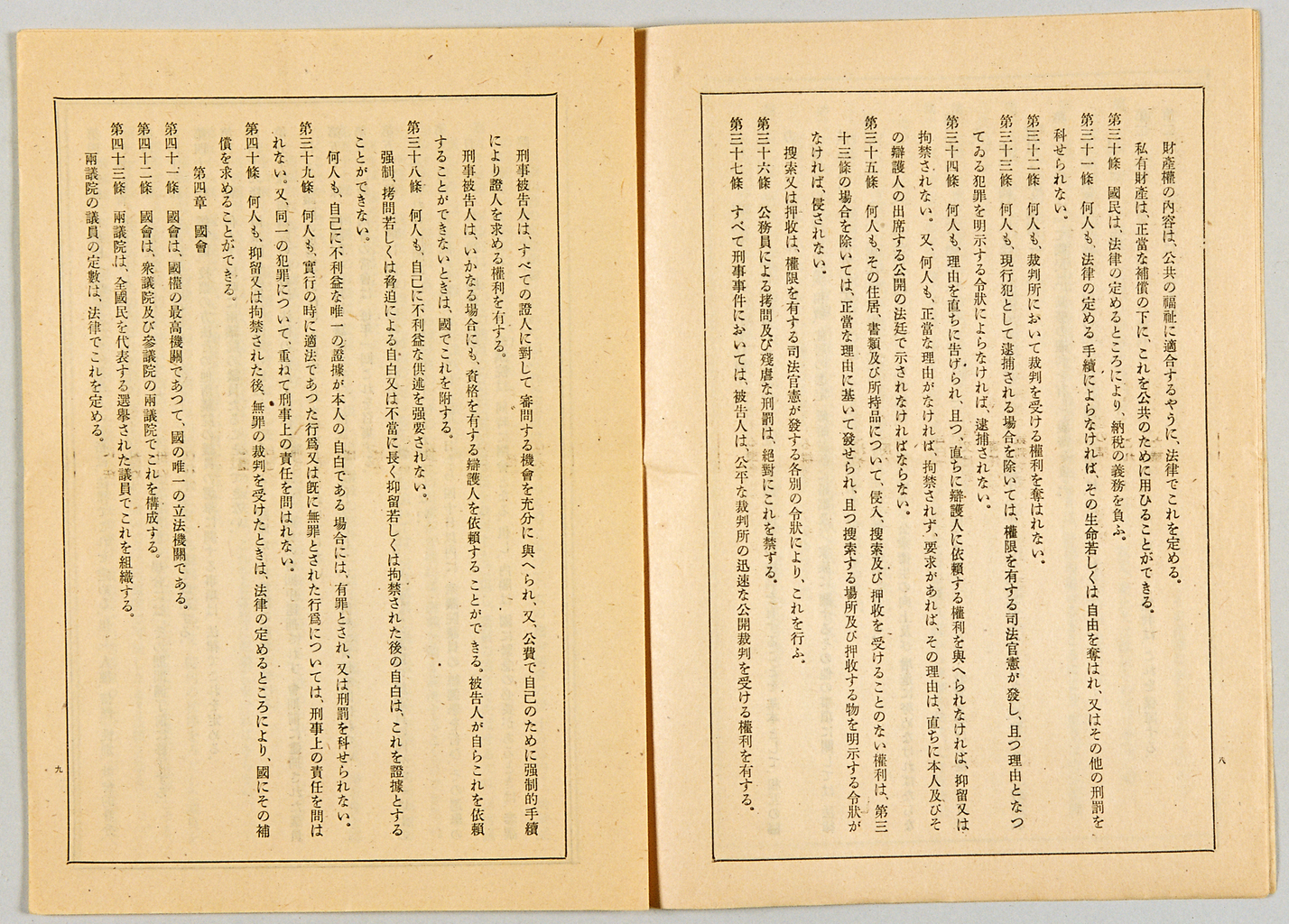

As such, the LDP has spent decades going through the motions of a party committed to constitutional reform – holding consultations, publishing draft reforms, debating proposals and counterproposals – without ever getting close to actually doing anything concrete about it. The venerable document, which will turn 71 this May, has never been amended or revised; but Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who is likely to be reelected for a third and final term in his party’s leadership contest this September, clearly sees constitutional revision as his motivating force, and seems committed to devoting much of his party’s energies and political capital towards that goal over the coming years.

Unfortunately for Abe, his party – thus far – doesn’t seem to be very good at working towards that goal. There are two major hurdles any constitutional revision must clear: first, it must garner two-thirds votes in both houses of the Diet; then, it must pass a public referendum with a simple majority. For many years, it was the first hurdle that looked insurmountable, but the LDP’s string of electoral victories have given it an enormously dominant parliamentary position, and even if it loses the votes of its coalition partner Komeito (which is a distinct possibility), there are enough pro-reform opposition politicians to push a referendum vote through parliament.

The LDP has spent decades going through the motions of commitment to constitutional reform without ever actually doing anything concrete about it.

This newfound confidence in the ability to clear the first hurdle has left the LDP looking for all the world like a group of people who just bought lottery tickets and are already loudly discussing what they’re going to spend the winnings on. Different groups within the party are consulting over what parts of the Constitution they want to change; the consensus is that the pacifist, war-renouncing (and generally tremendously popular) Article 9 is the priority, but the notions for changing it emerging from the party are often so radically removed from anything the Japanese public might support that one is forced to wonder how long it’s been since the authors actually left the LDP’s tobacco-stained headquarters building and tried talking to their fellow citizens. The latest such proposal comes from Shigeru Ishiba, former Minister of Defence and perennial LDP leadership challenger; Ishiba suggests that the LDP should hold a referendum on changing Article 9 to delete the second paragraph (which bans the holding of war potential and the state’s right to belligerence) and replace it with wording establishing the existence of the SDF’s land, sea, and air forces, and enshrining their mission as the maintenance of Japanese independence.

While Ishiba’s submission is undoubtedly a piece of political theater ahead of his inevitable leadership challenge to Abe in September (which, failing some extraordinary scandal embroiling the administration, will equally inevitably fail, as Ishiba is deeply isolated within the parliamentary LDP), it’s a solid example of the kind of things that have been forthcoming from constitutional reform daydreamers across the party. With the two-thirds vote target finally within the LDP’s grasp and the Prime Minister devoted to the cause of reform, they find themselves seemingly unable to separate the idle dreams of constitutional reform they mused upon in the past – in the absolute safety of knowing that reform was simply not on the table politically – from the contemporary requirement for a reform proposal that won’t utterly humiliate the LDP’s leadership by being smacked down in a referendum vote.

They are unable to separate idle dreams of constitutional reform from the contemporary requirement for a realistic proposal

It’s important to understand why it is that the LDP has never really thrown its weight behind constitutional reform in the past. Public opinion in favor of the Constitution plays a big part in that, but it is matched by the practical reality that by and large, a little patience and political strategizing has allowed the LDP to achieve its goals without needing an outright reform. To do this, the LDP has taken advantage of Japan’s incredibly tame and docile Supreme Court to give it leeway in interpreting and re-interpreting the constitution, and especially the war-renouncing Article 9, in increasingly broad ways. This approach has been applied right from the initial creation of the Self-Defense Forces (a military bound by practical and theoretical limits which supposedly bend but do not break the Constitution’s prohibition on the maintenance of “war potential”), through various revisions of the SDF’s mission and role, right up to the relatively recent and highly contentious reinterpretation of Article 9 to permit mutual self-defense operations – in which SDF forces may, under certain circumstances, come to the defense of Japan’s allies.

Each reinterpretation of the constitution has been controversial in its own time, with scholars, activists, and opposition politicians lining up to claim that each new interpretation has finally bent the constitution beyond its breaking point. The Japanese Communist Party, perhaps to its credit, has maintained a firm line on this issue throughout the post-war era, and still argues that the very existence of the SDF – the first major “reinterpretation” of Article 9 – is unconstitutional. Other opposition parties long ago decided that that particular hill was not worth dying on, not least since the SDF is also fairly popular among the Japanese people thanks to their important role in disaster relief operations.

This reflects a long-standing pattern: a new interpretation gives Japan a little more military wiggle room, opponents argue that it is unconstitutional, time passes and it becomes the new status quo. This has restricted the LDP’s ability to reform Japan’s security position – such changes can only be small and gradual, allowing time for the previous change to be accepted before proposing the next – but it has also allowed the LDP a degree of flexibility in security policy which it would almost certainly be denied if it went to the country for permission in a constitutional reform referendum. Think of it as a political form of “asking forgiveness, not permission”; the Japanese people would almost certainly have rejected any constitutional reform that radically changed Article 9, but have ultimately been willing to accept gradual changes in the status quo, as long as each step was given time to bed in and prove that it was not, in fact, either a disastrous return to pre-war militarism or a pledge to join in U.S. military adventurism.

Abe’s modest proposal is a political form of “asking forgiveness, not permission”

While Shinzo Abe may have had more grand ambitions for constitutional reform when he returned to the prime minister’s office in 2012, they have been tempered significantly by political reality. His proposal is now to leave Article 9’s existing language alone, simply adding an extra line on the end acknowledging the existence and role of the SDF. Some critics have argued that such a minor amendment is almost a tacit admission that the JCP’s claims of the SDF’s unconstitutionality have been right all along – and there is a danger, of course, that the public will view the amendment as so minor as to be unnecessary and time-wasting, thus choosing to vote it down simply to kick the Abe administration in the shins, a proclivity they have demonstrated several times recently in “second-order” elections.

Yet Abe seems to have come to understand, as Ishiba and other more aggressive reformists do not, just how narrow the line he must walk to achieve constitutional amendment really is. His proposal may be minor, but it has the unquestionable benefit of being a constitutional acknowledgement of a widely accepted status quo, not a conferral of new powers or a broadening of the SDF’s mission. It may infuriate hardliners, but “we already all accept this situation, isn’t it only right that the Constitution should catch up and reflect the reality of things?” may be pretty much the only campaign approach that will have a decent chance of winning a referendum. Anything more radical would be enormously controversial, would energize and mobilize widespread opposition, and would likely see Abe’s long run as prime minister ended not with the triumph of a historic reform, but with a David Cameron-like electoral humiliation.

Now the real question becomes whether Abe has the political capital and authority to bring his hardliners in line behind a vote on his moderate proposal – or whether, convinced that an ineffectual reform is worse than no reform at all, they rebel against Abe’s leadership and push constitutional reform back into the long grass for another decade.

Rob Fahey is an Assistant Professor at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study (WIAS) in Tokyo, and an Adjunct Professor at Aoyama Gakuin University's School of International Politics, Economics, and Communication. He was formerly a Visiting Professor at the University of Milan's School of Social and Political Sciences, and a Research Associate at the Waseda Institute for Political Economy (WINPEC). His research focuses on populism and polarisation, the impact of conspiracy theory beliefs on political behaviour, domestic Japanese politics, and the use of text mining and network analysis techniques for political and social analysis. He received his Masters and Ph.D from Waseda University, and his undergraduate degree from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.