Events overseas have, perhaps, rendered us all a little numb regarding the degree of scandal and corruption that a democratic leader can simply shrug off – but it bears emphasizing just how bizarre and grotesque the ongoing circus of the Moritomo Gakuen scandal and cover-up is within the context of Japan. This nation is no stranger to political scandal, but it has a long-standing and almost universally observed formula for dealing with them; the stony-faced press conference, the long, deep bow of apology as the cameras flash, and the senior government figure pictured leaving their office for the last time in the back of a black sedan. Resignation is the remedy to scandal in Japan, and properly handled it can even allow a political career to be resuscitated after a few years in the wilderness.

The Abe administration is no stranger to this formula – it was how a bribery scandal around Economic Revitalization minister Akira Amari was handled, for instance – yet in what is now arguably the most damaging scandal of the past decade or more, there has not yet been even a hint of willingness to consider resignation from any senior political figure. The most powerful men in Japan claim, with straight faces and a tone of wounded outrage that any other explanation could even be considered, that bureaucrats simply took it upon themselves to illegally falsify documents in order to protect the Prime Minister and his deputy. Bureaucrats’ careers, then, are to be held up as a sacrifice in place of the politician’s job that adherence to Japan’s scandal formula would demand.

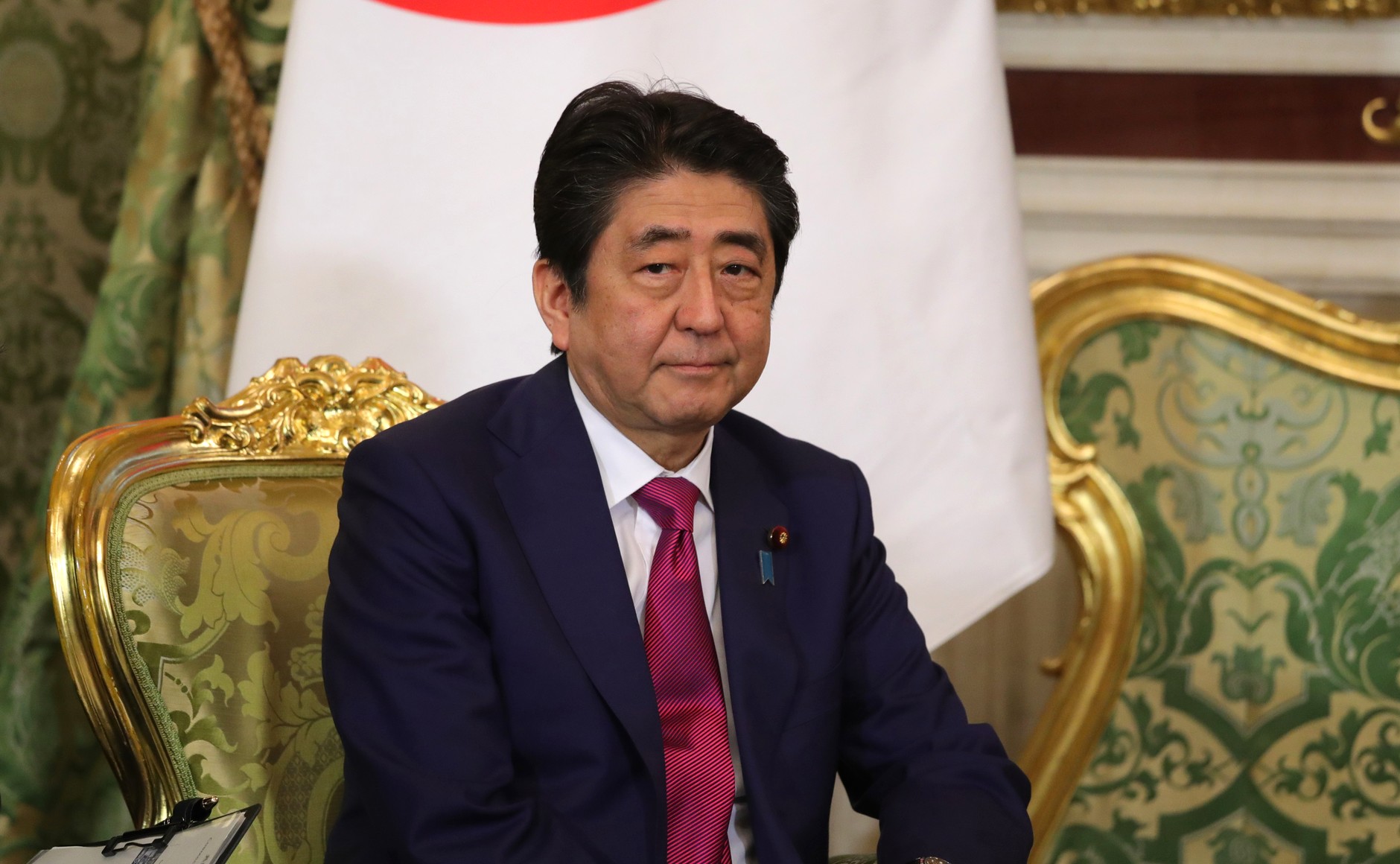

Abe is nothing if not stubborn and pugnacious; he will refuse to resign in disgrace

In a way, it might even work. There’s every chance that both Shinzo Abe and Taro Aso will continue in their roles through to September, when the LDP elects a new president (and thus, de facto, a new prime minister of Japan). It is also entirely probable that Abe will take his ability to survive until September not as an opportunity to retire gracefully at the end of his term, but as a sign that he should throw his hat into the ring for a third term. Abe is nothing if not stubborn and pugnacious; he will refuse to resign in disgrace, and it seems unlikely that he’ll take the option of stepping down in September either. The LDP’s membership will undoubtedly shuffle their feet uncomfortably, but with no major election on the horizon for a year and no serious contender to challenge Abe (bar Shigeru Ishiba, who is far to divisive to win the leadership in anything but an outright existential crisis), the best betting odds right now would be on the party muttering and grumbling but still ultimately falling in behind Abe and duly electing him for a third term.

And what a third term that will be. Any optimism among Abe’s camp that the Moritomo scandal will just blow over should be quickly extinguished; this stench is never, ever going to leave the Prime Minister, not so much because of the details of the scandal itself (it remains likely that no smoking gun connecting the Abes to the Moritomo land deal will ever be uncovered) as because of the sense among many voters that it confirms their deeply held suspicions about Abe. Moritomo will hang in the air around his government as long as he remains leader; it will undermine his authority both within his own party and as a national leader.

Abe’s third term would be beset by fragmenting party unity, public hostility and an emboldened opposition

For Abe, the consequences of that will be difficult to bear. The Prime Minister is far from the monstrous figure his more excitable opponents try to paint him as, but he is unquestionably someone who chafes against rules and is irritated by the checks and balances on the authority of his office – indeed, it’s precisely this tendency that has landed him in such hot water in the first place. His third term is likely to see him wading through thigh-high mud to get anything done; beset by fragmenting party unity (especially as lawmakers in marginal districts start to see him as dead-weight on their career ambitions), by public hostility that will likely express itself in a series of humiliations in second-order elections, and by an emboldened opposition anticipating major gains in next year’s elections. Combined with the stark realization that Abe’s much-vaunted hamburger and golf diplomacy with Trump has earned him almost nothing and left Japan sidelined in the United States’s handling of North Korea, the potential is for the Prime Minister’s historic third term to be just as aggravating and frustrating to him as his first, rapidly curtailed stint in the office was back in 2007.

Yet what is the alternative? For all the opposition bluster, all Ishiba’s chest-thumping and Shinjiro Koizumi’s carefully worded notes of disapproval, the chances are that the decision to remain lies entirely with Abe himself. Absent a true knock-out blow emerging from the Moritomo scandal, if the wounded Prime Minister chooses to limp on, it’s most likely he will succeed in doing so. That would be a gift to the opposition, who always do well when the public feels sick to the back teeth of LDP corruption – but weak and distracted leadership is the last thing the nation of Japan needs given the challenges of the coming years.

An earlier version of this article originally appeared in Tokyo Review’s newsletter, which is emailed directly to subscribers and includes a round-up of the best writing on Japan from our site and across the web, along with early access to this op-ed column. It’s free to subscribe, so sign up below!

Explore more of our coverage of the Moritomo Gakuen scandal:

[posts-by-tag tags=”Moritomo Gakuen” number = “5”]

Paul Nadeau is an adjunct assistant professor at Temple University's Japan campus, a visiting research fellow at the Institute of Geoeconomics, and an adjunct fellow with the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He was previously a private secretary with the Japanese Diet and as a member of the foreign affairs and trade staff of Senator Olympia Snowe. He holds a B.A. from the George Washington University, an M.A. in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University, and a PhD from the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Public Policy. He should be general manager of the Montreal Canadiens.

Rob Fahey is an Assistant Professor at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study (WIAS) in Tokyo, and an Adjunct Professor at Aoyama Gakuin University's School of International Politics, Economics, and Communication. He was formerly a Visiting Professor at the University of Milan's School of Social and Political Sciences, and a Research Associate at the Waseda Institute for Political Economy (WINPEC). His research focuses on populism and polarisation, the impact of conspiracy theory beliefs on political behaviour, domestic Japanese politics, and the use of text mining and network analysis techniques for political and social analysis. He received his Masters and Ph.D from Waseda University, and his undergraduate degree from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.