Japan’s new law governing short-term private rentals through sites like AirBnB – “minpaku” – came into force on June 15. The sector has been in desperate need of regulation, thanks to unscrupulous operators creating disruption and nuisance in many of Japan’s high-density residential areas – but the way the new law is being enforced is nothing short of a catastrophe. Tens of thousands of tourists face enormous cost and disruption, with around 80 percent of AirBnB properties being taken offline and thousands of reservations cancelled on short notice – with many thousands more still at risk.

This isn’t how the minpaku law should have worked out. On paper, the decision to properly regulate the sector was a totally reasonable compromise. AirBnB-type properties have risen to fill a valuable niche in Japan as tourist numbers have boomed in recent years and hotels have struggled to keep pace with the market. Up until now, however, most AirBnB properties have been illegal. The existing laws effectively required registering as a hotel, which was impossible for most operators. Rather than enforcing those strict and unsuitable old laws, the Japanese government chose to enact a looser set of regulations for minpaku which aimed to strike a balance between the needs of tourists, safety regulations, and the concerns of local residents.

Allowing local governments to set stricter rules has created a confusing patchwork of different regulations

Some of those regulations are sensible and consumer-friendly – such as insisting that minpaku meet similar fire safety standards to those demanded of hotels, or that the owner or their designated representative must live within a certain distance of the property, in order to be able to respond to problems rapidly. Other regulations, however, are more hostile; minpaku may only be leased for 180 days a year, for example, which is fine for those using AirBnB to earn a little income from spare rooms or properties they don’t use all year round, but disastrous for professional operators who buy or lease property specifically to offer as minpaku. Most problematic of all, however, is the decision to allow local governments to enact stricter rules – which has led to a confusing patchwork of different regulations in which some areas have banned minpaku entirely, while others only permit minpaku leases on weekends or on national holidays.

As the deadline for enforcement of this law approached, almost every actor involved in this scenario – the national and local governments, AirBnB and other booking sites, and even some of the minpaku operators – chose to act in ways which have led to a disruptive worst-case scenario. The Japan Tourism Agency told AirBnB and other minpaku sites to cancel reservations at properties which were not registered under the new law from June 15. AirBnB responded by removing the listings for all unregistered properties – shrinking its listings in Japan from over 60,000 to around 13,000 properties – but is only cancelling bookings at unregistered properties ten days ahead of the reservation date. A first wave of cancelled reservations disrupted the travel plans of thousands of tourists; for many tens of thousands more who hold reservations at now-delisted properties, they won’t find out if they actually have somewhere to stay in Japan until ten days before their journey. Minpaku operators, meanwhile, are rushing to register their properties; some have dragged their feet on getting the process underway, exacerbating the problem, but even those operators who have done their best to get registered report that some local governments have made the process incredibly slow and difficult, especially for foreign residents.

The government has legislated for the service AirBnB markets itself as – not the “grey market” industry it actually is

That the national rules are divorced from the reality of how minpaku operate is due in no small part to wilful misrepresentation on the part of AirBnB itself, which persists in promoting the notion that their offering means “staying in someone’s home.” In fact a significant proportion if not a majority of AirBnBs are operated as full-time tourist accommodation, often by owners who operate several such properties or by management companies on behalf of absentee investors. The government has legislated for the service AirBnB markets itself as – a platform for friendly, private transactions between people with a spare room and people wanting a place to stay for a few days – rather than the service AirBnB actually is, which is a platform that has nurtured a significant “grey market” industry involving professional investors, operators and service companies.

That reality makes the complaints of the hotel industry, who are often accused of pushing for minpaku regulation, look far more reasonable than just “shutting down competition.” Hoteliers aren’t targeting people who want to lease out a spare room or an unused vacation cottage every now and then; they’re targeting a professional industry that’s grown to offer tens of thousands of rooms around Japan without having to adhere to any of the safety, security, or customer service laws that apply to hotels.

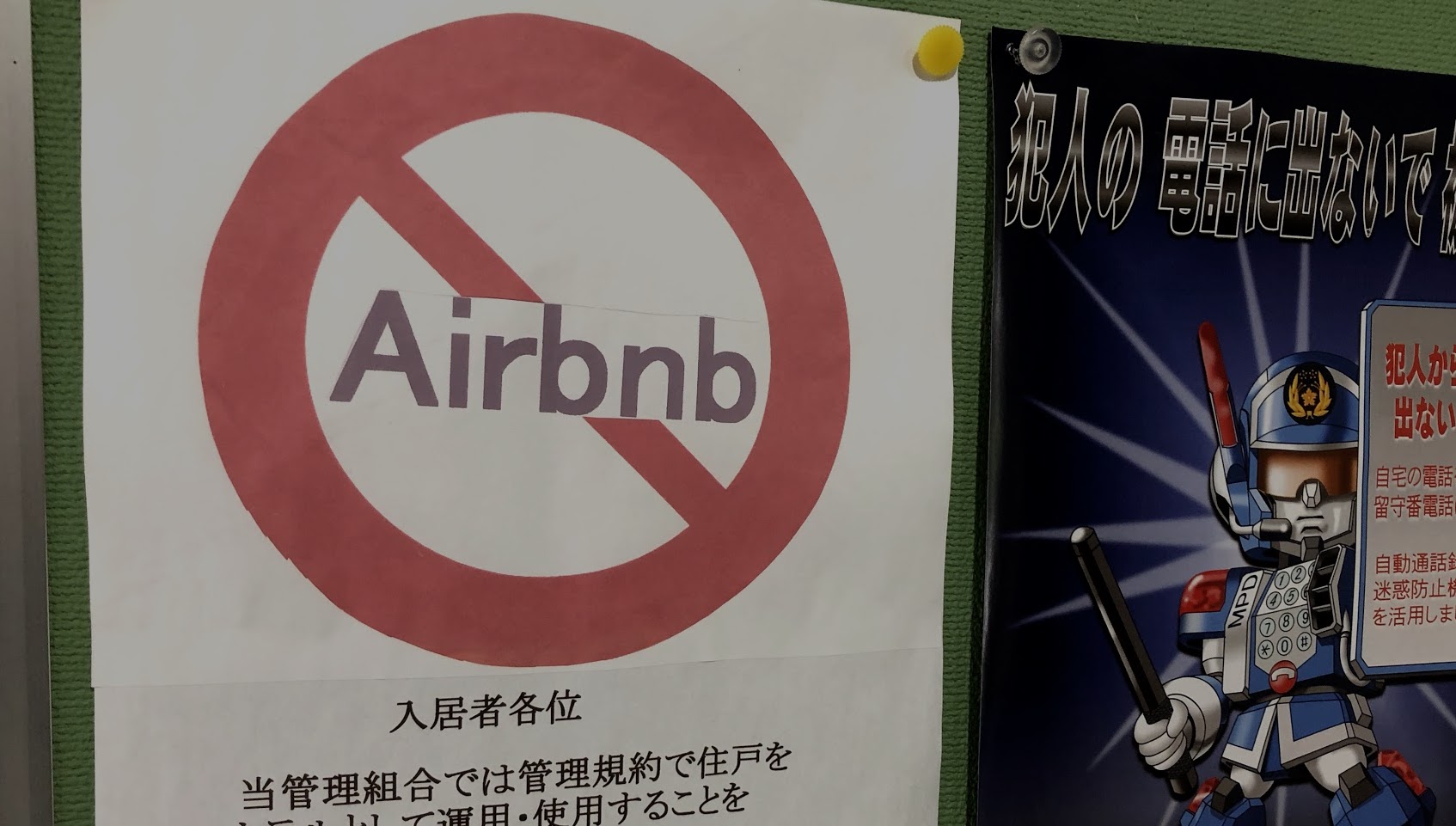

It’s not just hoteliers that drove demands for regulation, anyway; local governments have also been keenly aware of hostility to unregulated minpaku from residents. In many built-up residential areas in particular, the appearance of AirBnB type properties in apartment buildings has been hugely disruptive, with concerns over noise, rubbish and recycling issues, and treatment of communal spaces. Moreover, foreign residents who have always faced discrimination from landlords when trying to rent apartments are now confronted with even more suspicion thanks to unscrupulous operators who rent apartments to illegally sub-let on AirBnB. While there’s no doubt that a certain degree of xenophobia underpins some local government decisions to push minpaku out of their regions, anyone who has lived in a residential building or area in Japan should understand and empathise with the resistance to having a stream of short-stay tourists as neighbours. Residential areas in Japan are high-density and problems such as noise late at night, or rubbish being incorrectly separated or left out on the wrong days, can be a major problem for neighbours.

Thousands of tourists have become unsuspecting victims of a conflict between “disruption” and “regulation”

Coverage of the fallout from these new rules has tended towards heavy sighing and eye-rolling about what this says about Japan’s institutional competence to handle the visitor numbers it will receive for the Olympics in 2020, or to effectively scale its infrastructure to cope with the ever increasing numbers of tourists it hopes to welcome to the country annually. Sharp jabs about how poorly these cancelled bookings reflect the nation’s supposed “omotenashi” values are often thrown in for good measure. These are legitimate concerns, but the government’s responsibility to protect residents from nuisance and disruption caused by illegal accommodation businesses operating in residential areas should not be overlooked.

Caught in the middle of this conflict, however, are the many thousands of tourists who are the genuine and unsuspecting victims of the affair. Visiting the country as part of an economically vital tourism boom that has seen annual visitor numbers grow from around 7 million to over 28 million in the space of a decade, they have been treated with woeful disregard at every step in this unfolding farce. What the whole sorry affair amounts to is a case study in how not to handle the introduction of new regulations. Such cases – in which authorities move to regulate an industry that has been “disrupted” by a technology start-up, creating a mixture of positive effects for some consumers and negative externalities for others – will only become more common in future, both in Japan and elsewhere. Japan’s ill-considered approach should serve as a vital lesson in the importance of remembering the consumers trapped in the middle between disruptors and regulators – and this summer is likely to bring a torrent of angry, negative stories about Japan in the international press to drive that message home.

Rob Fahey is the CTO of VETA K.K., a Tokyo-based data science and survey technology startup, and an Adjunct Researcher at the Waseda University Institute for Advanced Study (WIAS). He formerly held academic roles including Assistant Professor at WIAS, Adjunct Professor at Aoyama Gakuin University's School of International Politics, Economics, and Communication, Visiting Professor at the University of Milan's School of Social and Political Sciences, and Research Associate at the Waseda Institute for Political Economy (WINPEC). He received his Ph.D from Waseda University.