Exactly one year ago, the level of alert on North Korea in the Japanese Ministry of Defense was at an all-time high. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) conducted its largest ever nuclear test, releasing 160 kilotons of energy. In comparison, the bomb dropped on Nagasaki released 20 kilotons. A Hwasong-15 inter-continental ballistic missile (ICBM), perhaps capable of reaching the entire continental United States, fell into Japan’s exclusive economic zone nine months ago on 28 November 2017.

These are respectively the last nuclear and missile verified tests carried out by DPRK to date. North Korea has now gone 365 days without nuclear tests and 279 days without missile tests, following a prolific year when the frequency of its tests was unprecedented. Since these milestones and the turn of the new year, North Korea’s stance has changed dramatically, suspending testing and coming to the negotiating table in a flurry of summits.

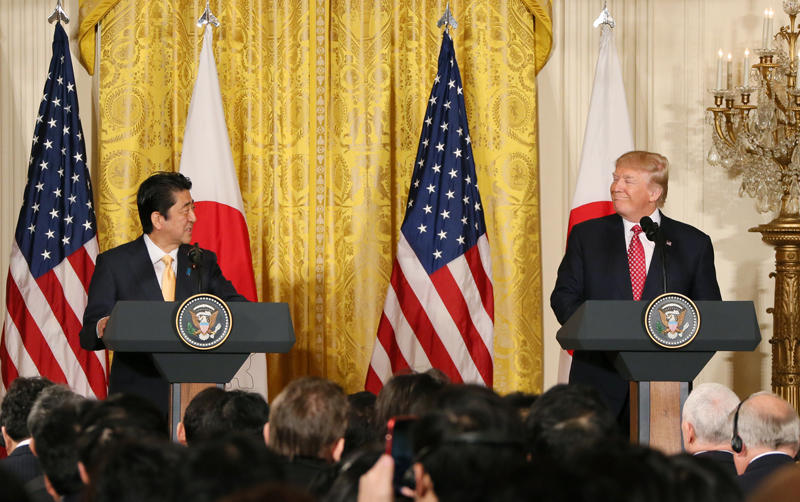

Whilst it is undeniable that U.S. President Donald Trump played a critical role in achieving the nuclear test-free year, the long-term success of his strategy is disputed and his methods have been controversial. China, South Korea and the United States are all on the scoreboard for summits – 3, 2, 1 – whilst Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has remained on the side-lines with zero summits to his name. He has been forced to rely upon President Trump and South Korea President Moon Jae-in to defend Japan’s interests.

Japan has not been left on the sidelines by its own will

The “highest priority” for Japan is the return of Japanese citizens abducted by North Korea, which Abe has invested substantial personal capital in, as the issue holds popular support domestically. The other key interest is for missile disarmament in North Korea due to Japan’s vulnerability to DPRK’s array of short and medium-range missiles, in addition to complete and verifiable denuclearization.

Japan has not been left on the sidelines by its own will. The possibility of a Japan-DPRK head of state meeting in September was widely reported in the media in June. In August, Japan’s Foreign Minister Taro Kono announced that Japan was ready for summit talks. However, calls for a summit were dismissed unless military exercises and efforts to boost readiness were suspended by Japan and ultimately a Kim-Abe summit in September has not materialized – barring any last-minute surprise.

The debate on the extent to which Japan should pursue a summit is growing fiercer. Discussions are taking place in the Prime Minister’s Office over whether to offer talks on economic cooperation to North Korea in order to win itself a summit to bring its own interests, particularly the abductee issue, to North Korea’s attention. Until now, resolution of the abductee issue has been primary to the release of economic assistance – the final sum of which could amount to $10 billion according to Nikkei reporting.

North Korea senses an opportunity to make steps towards delinking the U.S. alliance system.

The suspension of military exercises between the United States and South Korea in the Singapore summit between Trump and Kim has created a dangerous precedent, in which North Korea senses an opportunity to make steps towards delinking the U.S. alliance system. The concession made by the United States has raised the entry and exit costs for Abe into a summit. North Korea seems in no rush to have a summit with Japan and could arguably gain more by keeping Japan out in the cold. Even should these costs be considered necessary by Tokyo, expectations on the abductions issue are high in Japan and discussing economic assistance to a threatening nuclear neighbor is unlikely to be well-received by silver pacifists in fiscally strapped Japan.

A second summit between the United States and North Korea appears to be a “strong possibility” before the end of year, although there are obstacles including the resumption of military exercises by the United States and South Korea. Japan is rightly very skeptical of the sincerity of North Korea towards denuclearization, as supported by a report sent to the UN Security Council in August. c – denuclearization cannot be allowed by Tokyo (and Seoul) to progress along without being dealt together with dearmament, which is a view not shared by Washington who sees them as separate issues to be dealt with sequentially. The fear is that Trump will ignore Japan’s interests and make a further concession on the U.S.-ROK or U.S.-Japan alliance.

Such fear could push Tokyo to take its own independent action

Such fear could push Tokyo to take its own independent action, breaking off from policy coordination with the United States and South Korea. The Washington Post has reported that a top Japanese intelligence official secretly met with a senior North Korean official in Vietnam without the consent of the United States, damaging the good will of Washington who has been sharing information with Tokyo regarding its encounters with Pyongyang.

The situation could be even more complicated if the Trump administration decides to enforce Section 232 tariffs on automobiles. In the first case with the tariffs on steel and aluminum, Japan showed itself to be a meek ally and soft target for a bully. Exploiting Japan’s weak position in North Korea diplomacy, Trump is likely to think he can repeat another “great deal” akin to the renegotiation of KORUS, America’s free trade agreement with South Korea. It showed that the Trump administration is not aware of the dangerous geopolitical risks to its own alliance system caused by bargaining with allies for economic gains when their security is at stake. Tariffs on automobiles could force Japan to push back against the United States. In the worst case scenario, if Trump secures a second summit with Kim and the United States places tariffs upon Japan, it would become politically impossible for Abe to stand by and ask for Trump to protect Japan’s interests in a second Trump-Kim summit, whilst the core industry of his country’s economy receives a full frontal attack from the United States.

Abe is feeling two sources of pressure – secure a summit soon but do not pay too high a cost – both made more difficult by Trump’s unhinged actions. Whilst all might seem well after a nuclear-free year, North Korea has been sowing the seeds to sever policy coordination between Japan, the United States, and South Korea.

Harry Dempsey is an analyst for Anniversaries, Inc., a new U.S.-Japan relations think tank. He has worked as a research associate at the Asia Pacific Initiative (API) and as a researcher at Shinko Research (part of the Kobe Steel group). He has additional experience at the British Embassy Tokyo and London Research International. He was on the JET Program in 2014-15. He holds a BA in philosophy from Cambridge University.