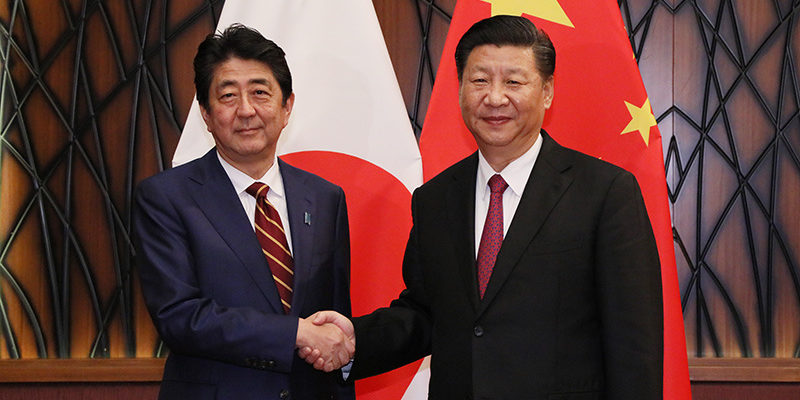

Later this month, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will visit Beijing for a summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping on October 26. This will mark the first visit to China by a Japanese prime minister since the Abe’s immediate predecessor, Yoshihiko Noda, visited in late 2011. Abe’s decision to visit now, as relations between China and the United States worsen over trade, is no coincidence; bilateral relations and trade will likely be a cornerstone of his visit, along with discussions of regional governance.

Belt and Road Initiative

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will be a major agenda item on Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Beijing. After initially being skeptical about the program, Prime Minister Abe shifted his position on the BRI earlier this year and following a visit by Premier Li Keqiang to Tokyo in May, Japan and China agreed to develop joint projects in Southeast Asia as part of the BRI scheme. Proposed projects aim to promote cooperation between Chinese and Japanese companies in third countries, while improving private-sector business dialogues.

For Japan, engagement with BRI – at least on terms that might grant Tokyo some degree of control, interlocking with its own “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” strategy – essentially amounts to hedging the nation’s bets in the face of uncertainty about U.S. commitments to the region. For China, meanwhile, current financial instabilities and questions regarding the nation’s ability to build the BRI have indicated that Beijing needs all the help it can get with its BRI development projects. Existing projects have been problematic for both sides – with Beijing’s loans generating a debt trap for host nations, while also failing to show a return on investment for China. Tokyo can bring to bear extensive experience in developing in third-party countries as well as transferring risk-management experience to Chinese firms – capabilities that Chinese investors in the BRI have yet to grasp. Consequently, a forum focused on China-Japan cooperation in development projects in third nations is set to be held on the sidelines of Abe’s visit.

Bilateral Trade

Bilateral trade between Japan and China was seen as the hopeful bright point even amidst deteriorating relations during the height of their territorial spats. While the anti-Japanese riots in China in 2012 led to a significant drop in Japanese foreign direct investments, recent figures suggest a steady recovery and an increase in Japanese businesses in China. Chinese foreign investments in Japan have also reached new heights, following the successful entry of Chinese tech firms into the Japanese market.

Chinese markets can provide Japan with ample business opportunities – as demonstrated by the planned size of Japan’s trade delegation to China’s Import Expo in Shanghai a few weeks later, which will see almost 600 Japanese firms in attendance. Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Beijing should help to develop the already recovering bilateral trade relations – and if successful, may help to curb some of the broader risks posed by the Trump administration’s ongoing trade feuds. In promoting bilateral trade and mitigating the seven-year gap resulting from icy relations following the Senkaku Islands dispute and Abe’s election, both Japan and China can benefit from the increased flow of goods and technological transfers.

North Korea

While most of the summit will be focused on economic relations, the issue of North Korea remains a primary security concern for Japan and Prime Minister Abe. In spite of the Kim-Trump meeting in Singapore and thawing North-South relations, sporadic diplomatic engagements between North Korea and Japan have yet to develop into a high-level meeting between Pyongyang and Tokyo. One interpretation is that Japan has been deliberately sidelined in the negotiations – another is that Tokyo “misread the air” with its uncompromising stance and has effectively left itself out in the cold as South Korea and the United States pursue engagement. Consequently, Tokyo has recently toned-down its calls for a hard stance vis-à-vis the North and also retracted its proposed deployment of PAC-3 units around the country, citing lowered security concern over North Korea’s missile tests.

With Japan being largely sidelined from the ongoing diplomatic engagements between the Trump and Moon administrations and Kim Jong-un, it’s possible that Abe will try to capitalize on warming relations with Beijing to request that China play arbitrator between Japan and North Korea. Japan’s official line is that it will not engage with the North until the resolution of the abductee issue, which has limited Abe’s options in reaching out to Pyongyang – and with little evidence that the U.S. or South Korea is prioritizing Japan’s concerns in their engagements, China may actually be Abe’s best hope for staying relevant to the ongoing process.

How exactly that might work in practice is a complex question. China would undoubtedly want a significant quid pro quo in return for playing middle-man between Tokyo and Pyongyang. In return, Japan would want a guarantee from Beijing that any future talks would resume under the multilateral context. Without the support of the United States, however, any proposal for the reengagement of a multilateral framework will likely fail. Japan will need to carve out a role for itself in this process beyond demanding resolution of the abductee issue – which risks being left by the wayside if the other parties start to view it as a roadblock to progress. If dialogue between the two countries can be restarted, some broad discussion of a Japanese role in administering the denuclearization of the North or providing key logistical aid would help to ensure its place at the table in future negotiations.

Conclusion

While the October 26 summit will be the most important engagement between Abe and Xi so far and could help rekindle the Sino-Japanese relationship, the fundamental disagreements between the nations remain strong. Although rarely in the headlines any more, the Senkaku / Daioyu territorial disputes remain a thorn in bilateral relations as over 20 Chinese coast guard ships have entered the disputed waters in the first half of 2018, and these expeditions are unlikely to stop in the short term. Japan is also deeply wary of Chinese military buildups in the South China Sea and its expanding naval and aerial assets. Moving the relationship forward will require focusing on the positives and engaging over areas where cooperation is possible, while returning to quiet agreements to downplay areas of dispute. Only in this way can Prime Minister Abe’s visit to China lay the groundwork for future cooperation.

Leo Lin received his M.A. in International Relations from Waseda University and his B.A. in Asian Studies from the Elliott School of International Affairs at the George Washington University. Currently a researcher based in Tokyo, his research interests include security policies in East Asia, and Chinese foreign policy with a focus on economic statecraft.