There are two stories about Shinzo Abe. The first story, the most commonly heard, is of a temperamental, impatient and vindictive Prime Minister – a man who chafes angrily at rules and protocols, who values nothing but loyalty and as a consequence has surrounded himself with sycophants of low ability. In this version of the story, almost six years as prime minister have only deepened Abe’s frustrations and worsened his temper as an endless parade of “obstacles” – the law, the media, the mere existence of rival lawmakers, public opinion polls and the Constitution of Japan itself – have conspired to stop the spoiled scion of a long political dynasty from making the mark on history he believes himself entitled to.

The second story about Shinzo Abe is that of a man greatly changed and matured after almost six years of leading Japan; a very different man to the one who returned to the prime minister’s office in 2012, much less the man who had a first abortive stab at the role in 2006. In this version, Shinzo Abe in 2018 has grown and mellowed; he has embraced incremental change and learned to take counsel on board in good faith. He is still a man who fervently believes in the value of loyalty and focuses strongly on personal relationships, but he is open to the value of strategy and alliance, even with those with whom he does not see eye to eye. This Shinzo Abe is a pragmatist not because circumstances force him to be, but because he is more flexible than his critics insist; perhaps pragmatism was even in his nature from the outset.

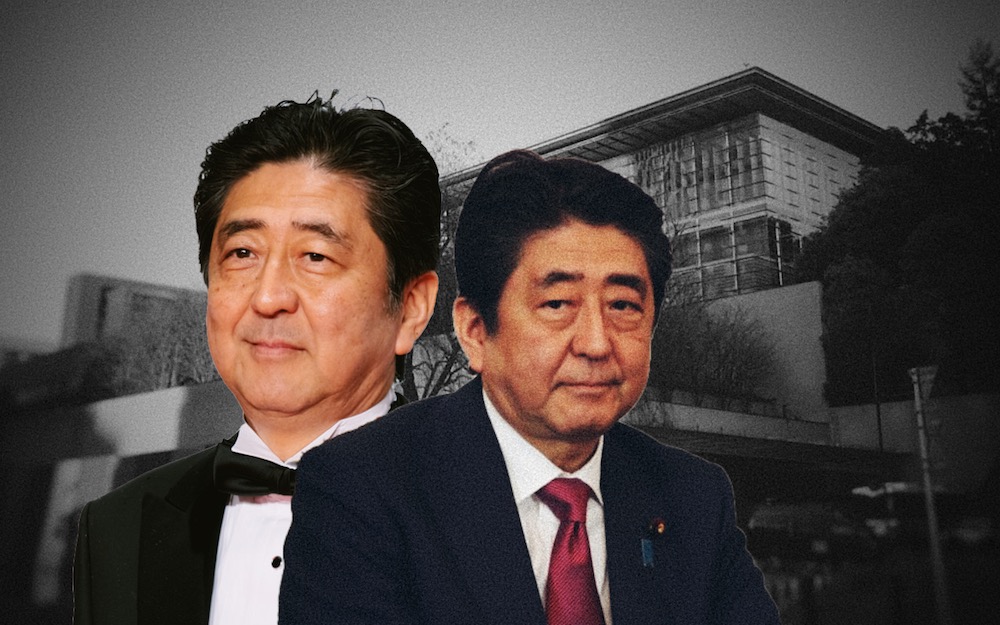

Both of these stories can’t be true, though some elements of both probably touch upon basic truths. The sclerotic Abe, the morose and frustrated Prime Minister sitting at the heart of the web of control he has woven around the Kantei, cannot coexist with the adaptable and pragmatic Abe who has learned and mellowed from years of experience. These warring narratives of Japan’s prime minister create a kind of Schrödinger’s Statesman – without direct observation, we can’t know which state Abe exists in. This often creates a cognitive dissonance in commentary around Japanese politics as it tries to handle the notion of Abe being part of both narratives at once.

If Abe has been smiling through gritted teeth, his third term is when the mask is most likely to slip

In Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment, the cat exists in a superposition until the box is opened and its final state is determined. In the case of Shinzo Abe, the box may be about to open. With his victory in last month’s intraparty election, he secured his historic third term and will become Japan’s longest-serving prime minister in due course. Much attention has been paid to that factor; less to the fact that this means, failing any major disasters or upsets along the way, that Abe will never again face a vote of his LDP peers. The term-limited Prime Minister must step down in 2021 – a hard deadline on his rule that means for the next three years, Abe is effectively unleashed. He no longer needs to feel encumbered by the unyielding electoral calculus of the LDP factions and the corresponding weight of alliances, of favours given and debts owed. If Abe really has been smiling through gritted teeth as he appointed people he dislikes to positions of influence; if he was holding back his temper as he confronted procedural blocks to his desired policies; then his third term is when that mask is most likely to slip.

Of course, there are good reasons to continue to be diplomatic, pragmatic and controlled, to the extent that Abe has been so in recent years. Abe won’t face reelection, but the LDP does face the public in House of Councillors and combined local elections next year. This is likely the last national election with Abe at the LDP’s helm, and as he has drawn the party tight around the prime minister’s office, every election now bears some element of referendum on the leader’s performance and likeability. Moreover, while Abe himself will step down in 2021, bowing out in a conflagration of bridges isn’t a great strategic move; he will remain de facto head of the party’s largest faction and will no doubt wish to retain power and influence, especially in the selection of his successor.

Such considerations, however, feel more like the calculation of the second Abe – the one who’s mellowed and become more strategic during his time in office – than of the frustrated and impulsive Prime Minister portrayed in critical accounts. If the dire warnings of the Prime Minister’s detractors are to come true, now is the time. Freed from the need to make nice with the LDP’s factions, lawmakers and local chapters, Abe can appoint his loyalists and confidantes to positions of authority with brazen disregard for factional arithmetic, punish those who failed to support his reelection bid with ostracization from the corridors of power, and ignore the policy minutiae that so frustrates him in favor of influence peddling on the golf course and throwing all his remaining political capital behind a myopic quest to make his mark on Japan’s history and its constitution.

In the face of major challenges, Japan needs its Prime Minister to be the best version of himself

We could also get some middle ground version of the Prime Minister; well-versed enough in the lessons of the past six years to avoid burning bridges within his party, but fixated on his personal legacy to the point of ignoring and holding back progress in other policy areas. In ways, this “Legacy Abe” would be the worst of all possible worlds; maintaining support within the LDP, such that he doesn’t face threats of removal or challenge from within, but still failing to engage with any of the serious and pressing issues that Japan faces and which, for better or worse, demand the attention and leadership of the Prime Minister. The version of Abe which wastes the next three years on a Quixotic quest for a largely meaningless constitutional change – one which he won’t achieve and which would merely acknowledge the status quo anyway – is one which would do a great disservice to the nation as a whole.

Abe’s post-election Cabinet reshuffle, due to be announced today, will be the first big test of which version of the Prime Minister, precisely, has been returned to power. Abe has form in picking cabinets based on personal loyalty rather than experience or competence; his poorly performing and scandal-dogged cabinet for his disastrous 2006-2007 premiership was dubbed the “Friends of Shinzo” cabinet (“otomodachi naikaku”, lit. “friends’ cabinet” – Michael Cucek’s “Friends of Shinzo” formulation just has a better ring to it) and he repeated similar errors in his reshuffle after 2016’s House of Councillors election. A return to this approach, rewarding confidantes with cabinet roles while excluding the “disloyal,” would be a red flag for the rest of the third term; but reports thus far concerning the imminent reshuffle suggest a fairly minor and conservative set of changes.

If the reshuffle passes without significant drama, it will be a good sign – because like or loathe Shinzo Abe, he is the prime minister Japan has for the next three years and the country keenly needs him to be the mellowed and pragmatic leader more optimistic commentators believe him to be. It’s not just the ongoing challenges posed by the economy, the nation’s accelerating pace of social change and the complex international relations environment of the Asia-Pacific; added to those challenges are the specter raised this summer of increasingly serious and regular natural disasters driven by climate change, not to mention the need to establish Japan in a leadership position in the international liberal order in the face of the Trump administration’s abrogation of the role. Few post-war prime ministers of Japan have faced quite such a difficult and complex set of tasks. As long as Shinzo Abe continues to lead, Japan needs him to be the best possible version of himself.

Rob Fahey is the CTO of VETA K.K., a Tokyo-based data science and survey technology startup, and an Adjunct Researcher at the Waseda University Institute for Advanced Study (WIAS). He formerly held academic roles including Assistant Professor at WIAS, Adjunct Professor at Aoyama Gakuin University's School of International Politics, Economics, and Communication, Visiting Professor at the University of Milan's School of Social and Political Sciences, and Research Associate at the Waseda Institute for Political Economy (WINPEC). He received his Ph.D from Waseda University.