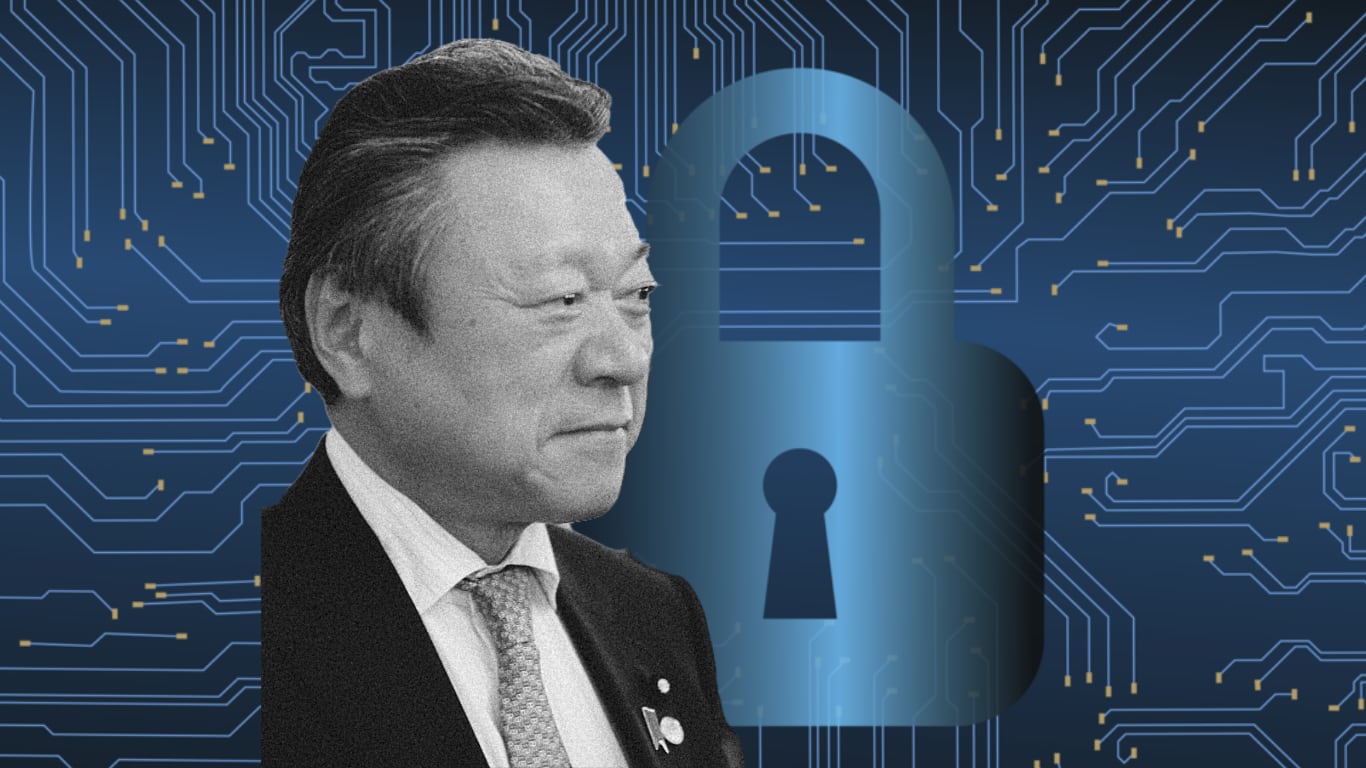

Japan’s Minister in Charge of Cybersecurity Yoshitaka Sakurada became a target of worldwide ridicule last week when he revealed during Diet questioning that he does not know how to use a computer. Doubts emerged when he seemed unfamiliar with USB drives, and when challenged directly, he responded by saying, “Since I was 25 years old and independent I have instructed my staff and secretaries. I have never used a computer.”1Kyodo News, 15 Nov 2018, “Japan’s cybersecurity chief says he has ‘never used’ a computer“ This immediately drew the ire of opposition politicians and the media alike. After all, the question of how someone who has no practical experience with computers is placed in charge of the nation’s cybersecurity policy is a legitimate one – and Sakurada only dug a deeper hole for himself by later asserting that “my biggest job [as Cabinet minister] is to read out written replies [prepared by bureaucrats] without making any mistakes.”2Japan Times/JIJI Press, 23 Nov 2018, “Japan cybersecurity minister who doesn’t use computers says he’s also not familiar with cybersecurity“

How does an appointment like this happen? How can someone who is not only not an expert in a specific subject, but entirely ignorant of its most basic underpinnings, become the minister in charge of a major nation’s policy in that field? Amid the obvious ridicule aimed at Sakurada in the press has also been a degree of incredulity – but the fact is that Sakurada is far from being an isolated case. Understanding how he ended up in charge of cybersecurity offers a deeper insight into a political system that has seen its fair share of under-qualified and over-titled cabinet ministers over the years.

Simply put, Yoshitaka Sakurada earned his dual ministerial appointments – he serves as both Minister for the 2020 Olympics and Minister for Cybersecurity – based on intraparty favors and seniority instead of merit. August’s cabinet reshuffle followed the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) presidential election, in which support from the party’s various factions was key in giving Prime Minister Abe not just a victory (which was a foregone conclusion), but a strong enough victory to keep hopes for his policy agenda alive. Toshihiro Nikai, the Secretary General of the LDP, is leader of the party’s third smallest faction but was among the first to throw his faction’s support behind Abe. As a result, Nikai’s faction was gifted three of eighteen senior cabinet postings (16% of posts, for a faction comprising just 10% of LDP Diet members). Sakurada, like others, had the requisite seniority (generally measured in the number of times a member has been elected) and factional affiliation to earn a post – and so he was duly handed a cabinet position despite his unfamiliarity with the issues.

Even individuals without a modicum of merit can earn cabinet positions by staying in the Diet for long enough

The practice of using cabinet appointments to manage political allegiances is nothing new, and Sakurada is far from the first dramtically underqualified Minister. Shigeru Yoshida (Prime Minister from 1946-47 and 1948-54) made a habit of shuffling cabinet ministers frequently, and Eisaku Satō (Prime Minister from 1964-72) established a precedent for apportioning cabinet appointments among the party’s factions based on their size. As a result, most cabinet ministers in postwar administrations serve an average of about a year—hardly enough time to learn the bureaucracy or become policy experts if they did not enter the office with experience and knowledge. This also meant that individuals could earn cabinet appointments without even a modicum of merit simply by staying in the Diet for long enough and associating themselves with the right faction. This system has been the genesis of many a ministerial gaffe over the years.

A few highlights from recent memory include the following:

The previous Minister in charge of the Northern Territories Teru Fukui did not know how to pronounce one of the names of the northern territories—of which there are only four.

Fukui’s predecessor as Minister for Okinawa and the Northern Territories Tetsuma Esaki called himself an “amateur” on the subject and admitted that he has to rely heavily upon the bureaucracy.

Tomomi Inada had no defense experience prior to becoming Minister of Defense, and among other missteps, her politicization of the position drew criticism over her qualifications. She became the first Defense Minister to sign off as the Minister of Defense in the guest book at the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, doing so immediately after returning from a reconciliation tour in Pearl Harbor, and violated non-partisanship rules by calling for Japanese voters to support the LDP on behalf of the Ministry of Defense and Self-Defense Forces.

Appointing under-qualified ministers is not the sole preserve of the LDP, either. In 2010, the Democratic Party of Japan’s Justice Minister Yanagida was forced to step down because he bragged to constituents that he has two canned answers to carry him through Diet questioning: “I won’t comment on individual cases,” and “I’m acting in accordance with the law and the evidence.”

Naming a figurehead as Minister for Cybersecrity gives those issues budget and policy priority

Is it not problematic – or even dangerous – for ministers with such a poor grasp of their department’s brief to be appointed? To answer that question, it is important to understand the cabinet postings themselves. The Prime Minister is well aware that the cabinet will be comprised of friends, tentative allies, and even enemies. He may appoint up to eighteen cabinet ministers, eleven of whom must be in charge of the government’s established ministries. In order to highlight policy and budget priorities, the Prime Minister often creates ministerial positions even if there is no formal bureaucratic organization underneath them. In those cases, the ministers are nominally in charge of policy coordination, decisions, and responding to questions in the Diet. If the Prime Minister wants to show that he is giving priority to a certain policy while still retaining control over it either within his own office or the bureaucracy, he often appoints someone who has little to no chance of actually influencing that policy. This is often true for ministers who are given multiple titles; for example, Mitsuhiro Miyakoshi currently serves as the Minister for Ocean Policy, the Minister for Okinawa and Northern Territories, the Minister for Consumer Affairs and Food Safety, and five other titles. It is safe to assume that Miyakoshi is not an expert in every single one of those widely disparate issues.

Hence, that the Minister for Cybersecurity does not use a computer is no indicator that Japan’s cybersecurity policy is in peril. By naming a Minister for Cybersecurity, Prime Minister Abe gave cybersecurity issues budget and policy priority – and by appointing a minister who had no experience or insight, and hence no interest or ability to influence decision making, he effectively created a figurehead and entrusting the actual creation and execution of cybersecurity policy to the bureaucracy. Speeches, public statements, and answers offered in the Diet are all prepared by bureaucrats. Legislation is drafted by party and government officials (not by congressional staffers, like in the U.S.). Cybersecurity policy decisions are coordinated by the well-staffed and operated National Security Secretariat.

The real issue with Sakurada is not his computer illiteracy or lack of insight into cybersecurity issues; it is his failure to present a confident and competent face in Diet questioning and the resulting risk he poses to confidence in Abe’s cabinet. If the ridicule surrounding Sakurada leads to a dip in public opinion of the cabinet it will result in diminished political capital for Abe. Abe will try to hold together this “All Hands Baseball Team” Cabinet3Tokyo Review, 4 Oct 2018, “Abe’s 2018 Cabinet Reshuffle, Explained (Part II)“ until after the House of Councillors election next summer, at which point he will be free to conduct another cabinet reshuffle. However, if Sakurada’s gaffes seem to be causing a problem in the polls, it’s likely that Abe will leverage Nikai to force Sakurada out of the cabinet.

Observers and analysts of Japan might ask themselves a broader question – whether the domestic and international opprobrium for Sakurada’s gaffes might force the LDP to break with precedent and begin to take ministerial qualifications for their roles more seriously. The fact that Sakurada was nowhere near the first underqualified LDP Minister to come under fire, however, suggests that he is also far from the last.

Michael MacArthur Bosack is the special advisor for government relations at the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies. He previously served in the Japanese government as a Mansfield Fellow.