Welcome to the first installment of Sino-Japanese Review, a monthly column on major developments in Sino-Japanese relations that provides a running commentary on the evolution of this important relationship and helps to put current events in perspective. Previous installments may be found here.

The end of 2018 saw China and Japan working together to preserve the positive momentum out of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to China in October. The first such visit since 2011 had marked the culmination of four years of slow but steady rapprochement following an intense confrontation surrounding the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. This rapprochement is rooted in China and Japan’s common desire to bring back some stability to a crucial relationship, but the protectionist turn of the United States has served to greatly accelerate it by uniting the two countries in defense of the free trade based international order upon which their economies depend. There are ample signs, though, that underlying sources of tensions in the relationship remain potent.

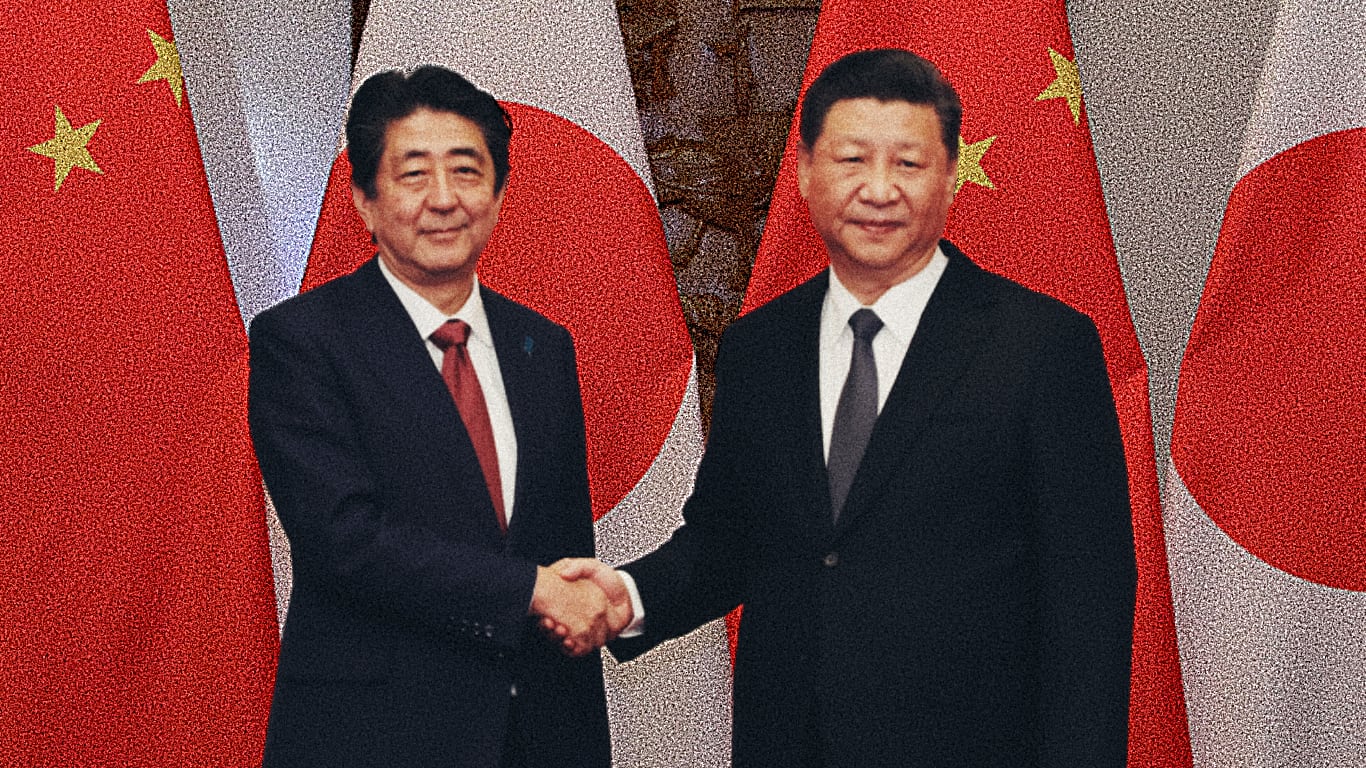

PM Abe and Chinese President Xi Jinping met again at the G20 summit in Buenos Aires in late November, reaffirming their commitment to strengthen communication and mutual understanding and to deepen economic ties. The eagerness of both sides to pose as advocates of free trade continued to provide common ground, as both Tokyo and Beijing reiterated their support for a swift conclusion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and of a trilateral free trade agreement between Japan, China and South Korea.

The East China Sea remains the most potent source of tension in Sino-Japanese relations

These pledges of friendship and cooperation stood in contrast with developments in the security sphere. Japan released new National Defense Program Guidelines that did not shy away from accusing China (and Russia) of seeking to alter the international and regional order. China was singled out for the lack of transparency in its defense build-up, for its expansionary activities in the South China Sea, and for seeking to change the status quo by force in the East China Sea through increased military activities and regular dispatches of Chinese vessels to the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.

Recent Chinese behavior confirms that the East China Sea remains the most potent source of tension in Sino-Japanese relations. Beijing conducted new exploration activities in gas fields close to the median line between the two countries’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). China in fact claims an EEZ that goes well beyond this line, basing its claims on its continental shelf, which extends up close to the Japanese archipelago. However, in this case – as in previous such occurrences – Chinese vessels remained on the PRC’s side of the median line.

Tokyo nevertheless condemns those activities, both for contravening the spirit of a 2008 agreement on joint exploration that remains unimplemented and because the gas fields in question straddle the median line. Japan’s reaction this time round, however, was more muted than in previous years, with criticism limited to comments by Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga during a scheduled press conference. Suga tempered his criticism by emphasizing Japan’s intention to resume talks and negotiations with China to resolve the issue. Similar statements in previous years (dating back to 2013) over gas developments in the East China Sea were not only more stern, but they were also reinforced by PM Abe, and by threats to take the issue to international courts. This shift to a dialogue-focused orientation, despite the continuation of Chinese activities, is a notable change.

On the Chinese side, too, the attitude toward potential disputes was more moderate in 2018. In late November, the Japanese Ministry of Defense announced plans to upgrade its two Izumo-class helicopter carriers to serve as aircraft carriers. In response, the Chinese Global Times quoted a military expert warning that this upgrade could endanger the improvement in Sino-Japanese ties and unpleasantly echoed Japan’s militaristic past. Another expert told the People’s Daily that this development threatened Japan’s “exclusive defense” posture, which a Foreign Ministry spokesman urged Japan to maintain.

China has also moderated its tone; the response to incidents in 2013 was far more alarmist

A comparison with Chinese reactions to the launch of the first Izumo carrier in August 2013 is instructive here. The concerns expressed then – use of the carrier for offensive purpose, signs of militaristic tendencies, raising of international tensions – may have been similar, but the tone adopted by both the Global Times and the People’s Daily were significantly more alarmist. The unveiling of the Izumo was linked with the country’s “political right-wing shift” and ostensible nostalgia for its imperial past. A defense ministry official expressed concerns and urged “high vigilance” regarding Japan’s expansion of its military equipment.

A toning down of Chinese rhetoric can be seen with regards to important anniversaries related to World War II history as well. Take the 15th of August, the day of Japan’s surrender. The anniversaries in 2013 and 2014 were the occasion of long accounts in the People’s Daily of Japanese war crimes and claims of insufficient repentance in the decades after. 2018’s anniversary saw the party mouthpiece instead limiting itself to a summary of various commemorative events held around the country and even noting the expression of remorse offered by the Japanese emperor in a speech on the same day. A similar tone of moderation prevailed around the December 13 memorial held yearly since 2014 in memory of the Nanjing massacre, Japan’s most infamous wartime atrocity. Xi Jinping attended the inaugural event, and attended again in 2017, with the People’s Daily dedicating parts of its first page to the occasion every year. In December 2018, no senior leader attended, and the memorial was relegated to page four of the newspaper.

These examples remind us that, although security, territorial and historical issues remain important friction points – each and any of them capable of causing a return to Sino-Japanese confrontation in case of unforeseen incident or provocative action by either side – the way they are handled and managed by the two governments is not fixed and depends on the overall health of the relationship. Indeed, the link between underlying sources of tension and general stability in the relationship runs both ways. An accumulation of small incidents can certainly wear down and frustrate senior officials, making it harder to keep Sino-Japanese relations on an even keel, but determination at the top to maintain stability can also mitigate some of the negative impact of the lingering unresolved issues that keep China and Japan apart.

“Sino-Japanese Review” provides a monthly analysis of major developments in Japan’s relations with China, as well as background and insights on their broader implications on international relations.

Andrea A. Fischetti is a government scholar conducting research on Asia-Pacific Affairs and East Asian Security at the University of Tokyo and at the Asia Pacific Initiative. He was a visiting student at the Hiroshima Peace Institute of Hiroshima City University, and a research assistant at the House of Commons in the British Parliament. Mr. Fischetti earned his MA in War Studies from King’s College London, following a BA with First Class Honours in International Relations, Peace and Conflict Studies.

Antoine Roth is assistant professor at the Faculty of Law of Tohoku University, working on Sino-Japanese relations, China's foreign relations, and East Asian international affairs. He holds a PhD in International Politics from the University of Tokyo and a MA in Asian Studies from the George Washington University and a BA in International Relations from the University of Geneva. He has previously worked at the Swiss Embassy in Tokyo and has been a visiting student at Fudan University in Shanghai.