Editor’s Note: this is the first of a new series of articles related to the imperial abdication and ascension scheduled for late April/early May 2019.

There are fewer than five months left before Japan’s Heisei Emperor abdicates and his son, Crown Prince Naruhito, accedes the throne. When that happens, the Heisei era ends, and a new one will begin. What that era will be called is still unclear, but at least we now know when the new era name will be announced – the government recently ended significant speculation over the timing of the announcement by revealing that it will announce the name on April 1st. The debate over when to announce the era name highlighted a potential administrative problem that could affect the government, private sector, and ordinary residents of Japan.

While Japan also uses the internationally recognized common era system based on the Gregorian calendar, the imperial era name system predominates forms and records across the public and private sectors. This imperial era naming convention is known as gengo (“era name”), and it means dates are written as the year of a particular imperial reign: for example, “2018” was “Heisei 30 nen,” the “30th year of Heisei.” While it can be confusing for those who don’t know the system, it is a part of everyday life in Japan. When residents visit hospitals, the forms ask for birthdates in gengo; when government staffers keep official records, they use the imperial naming convention; even Self-Defense Force exercises use gengo, so 2017’s Joint Exercise Rescue (JXR) was called 29 JXR after “Heisei 29.” Importantly, these records are not usually dual-labeled; they are stored digitally or physically by common era or gengo but not both. The fact that gengo is so widely used means that all documents, calendars, and records (and the systems recording them) created after May 1, 2019 will need to be updated with the new imperial era name.

That process will take time, hence the debate over when it would be appropriate to announce the new era name. Pragmatists argued that the new name should be decided upon and announced as early as possible before the imperial abdication and ascension to allow for systems, forms, and products to be updated. Conservatives, especially those with ties to Japan’s right-wing special interests, argued that traditions be respected by withholding announcement of the new era name until a formal proclamation is signed by the new emperor. This debate raised four questions:

- Why not just use the common era for official records and gengo for ceremonial purposes?

The short answer is that it is the law. The former Japan Socialist Party raised this question in the Diet in the late 1970s, and the ruling LDP’s response was to formalize the gengo system in the 1979 Era Name Law. It happens to be the shortest law in effect today with only two provisions (first, the government decides the era name, and second, there will only be one era name per imperial reign) so the lack of clarity opens the door to debates such as the one that took place last year.

The long answer is that enough of the Japanese public continues to support the use of gengo. In a recent Yomiuri poll, 50 percent of those surveyed said they want to use gengo in their daily lives, while 48 percent said they do not. For some Japanese, it is a matter of tradition; for others, a way of marking important periods of history. For still others, it comes down to the status quo. Certainly, converting old records filed under gengo would be a massive administrative undertaking, and it may be easier simply to do things the way they have been done for decades. Ultimately, the reality is that there is not enough public demand to warrant challenging the existing system.

- Who makes the decision on the era name?

By law, the final authority for decision of the era name is the cabinet, with the new emperor proclaiming their chosen name by written order on the day of his ascension.

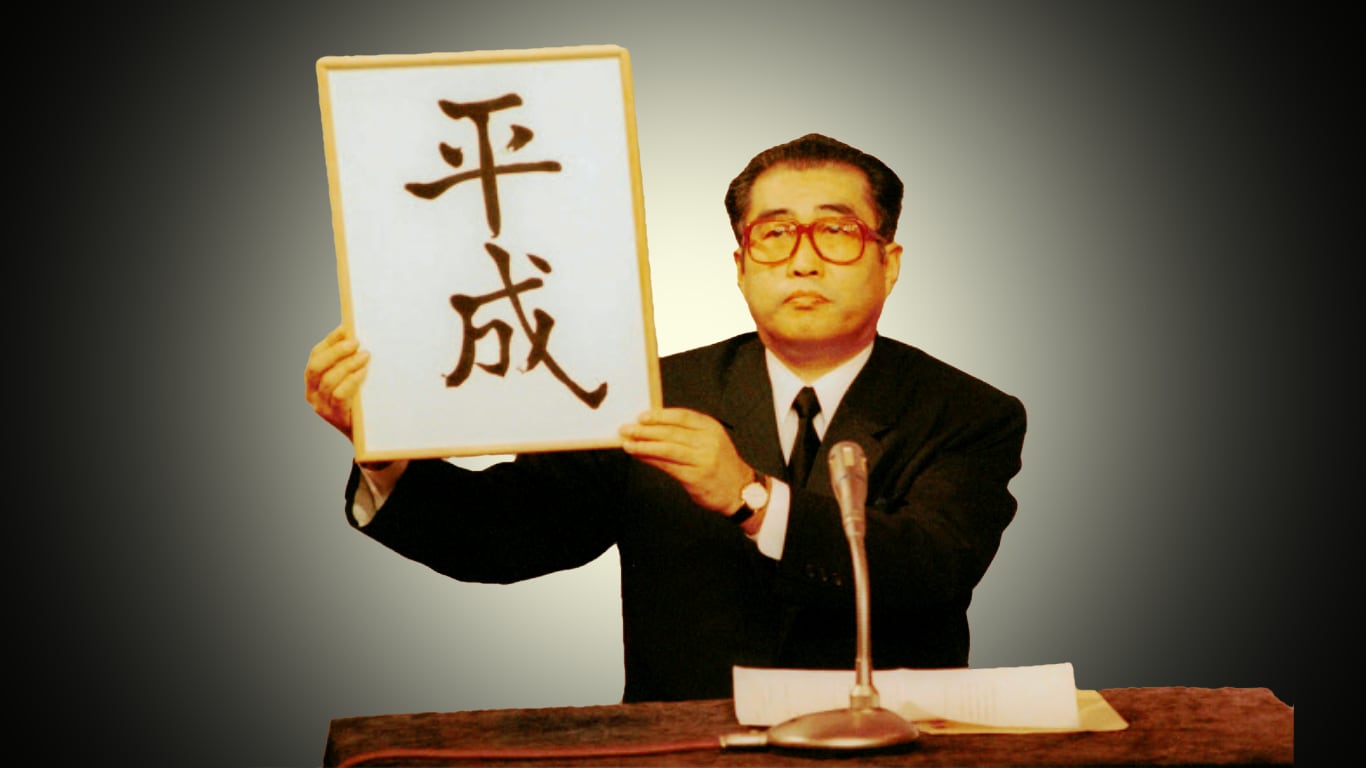

In practice, the responsibility is left to cabinet-appointed bureaucrats and specialists who sift through candidate names and pick a short list for approval. The kanji characters are traditionally selected from ancient Chinese texts and are meant to carry significance for the expectations of the new era. For example, Meiji meant “enlightened rule,” a signal to the restoration of imperial rule; Heisei means “achieving peace,” alluding to a Japan that was moving beyond its wartime legacy.

Once the list of about three options is compiled, those are forwarded to the cabinet for a final decision. Through it all, the emperor (and by extension, the imperial family) is prohibited from influencing the process. Based on the Japanese constitution, the role of the emperor is strictly ceremonial and any attempt to influence decision-making could be seen as political in nature and in violation of Japan’s highest law. This contrasts with pre-1947 constitutional practices, where the emperor had veto authority over era name selection.

- Is it really that egregious to announce the era name early?

The answer to this question highlights a prevalent theme in Japanese conservative positions: logical incongruity. The conservatives who argued that the era name should not be announced early based their assertions on the precedent set forth in previous eras and the tradition of only ever having one era name during an emperor’s reign. They couched this argument in the assertion that the Japanese imperial line has remained unbroken since time immemorial. But in reality, era names were only formalized by the “one reign, one era name” government ordinance in 1868, following the Meiji Restoration. Prior to that, era names were subject to few fixed rules and changed often, with Emperors often choosing to declare a new era after a natural disaster or inauspicious event – for example the Emperor Komei had six era names within his reign.

Like many other “traditions” that conservatives now hold dear, the current system of imperial era names is really a product of the late 1800s, when a large number of national “traditions” were formalized (or in some cases, invented) as part of the “restoration” of imperial power. However, it is important to note that the Meiji Emperor was 15 at the time, and thus held little actual “power”. Since the Meiji Emperor, there have only been three era changes: Taisho (1912), Showa (1926), and Heisei (1989). The current transition also represents the first abdication in over two hundred years. There is not much precedent to employ and no lengthy tradition to rest upon as justification for withholding an announcement, whether formal or informal.

Logical incongruities such as this are a common issue associated with the conservative policies towards the Imperial household. These are the same people that argue that imperial succession must only include male heirs, even though all emperors are supposedly descended from Amaterasu, a female deity. They ascribe divine significance to the royal family but lash out against members of that same family who disagree with their own prescribed version of the imperial way. In sum, they can create friction in situations which may be wholly unwarranted.

- Why would the Japanese government allow an issue that relates to the imperial throne (which is supposed to be apolitical) threaten smooth governance?

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s political connections to Japan’s right-wing elements are well-documented, so it is no surprise that the government showed some deference to the crowd arguing against early announcement of the new era name. The issue was not Abe’s alone, however, as right-wing members within the LDP were staunchly opposed to the early announcement and took steps to block any policy supporting it.

In the end, Prime Minister Abe sought a middle ground between the pragmatic and conservative positions – as he has on several other policy issues. The new era name will be informally announced on April 1st – late enough to placate the conservatives somewhat, but not so late that it completely leaves business and government sectors high and dry. Nevertheless, it appears the ten-day Golden Week holiday meant to mark the introduction of a new emperor will be filled with workers rushing to update records and systems to usher in the new era.

Michael MacArthur Bosack is the special advisor for government relations at the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies. He previously served in the Japanese government as a Mansfield Fellow.