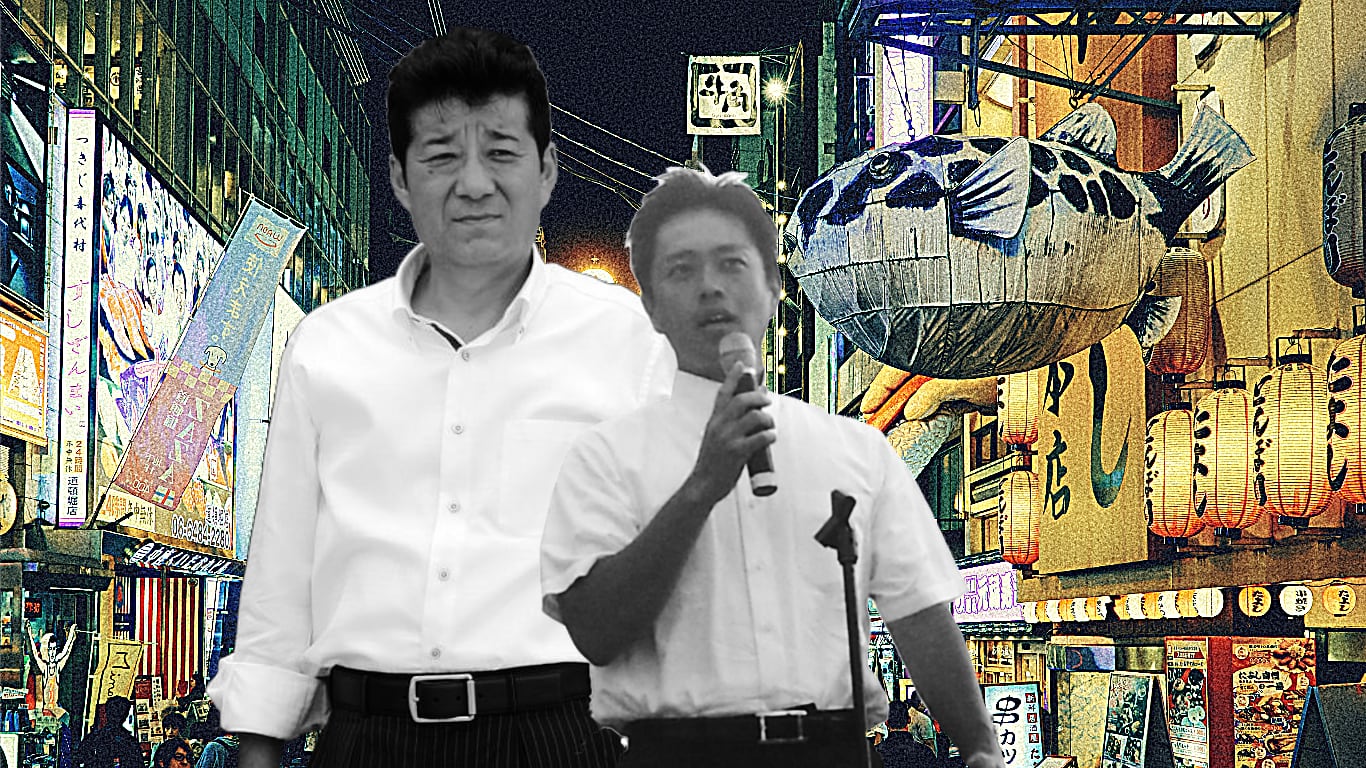

Japan is one of the world’s most heavily urban nations – 37 million people live in the densely populated designated cities and Tokyo’s special wards alone, while the World Bank estimates that 92 percent of the Japanese population live in an urban district of some kind – which makes the question of how those cities are governed an important political question. When much of the country goes to the polls for the last election of the Heisei Era on April 7, voting for 11 prefectural governors and six city mayors along with 41 prefectural assemblies and 17 city councils, the question of urban governance will dominate the contest in Japan’s second largest city. The races for mayor of Osaka City and governor of Osaka Prefecture were originally scheduled for November, but a pair of resignations has resulted in what’s being called a “cross-election:” the current mayor, Hirofumi Yoshimura, is resigning to run for governor, while the current governor, Ichirō Matsui, is resigning to run for the mayor’s office.

The motivation for this unusual strategy is the Osaka Metropolitan Plan – the crown jewel in the policy plans of One Osaka (also known as the Osaka Restoration Association, Ōsaka Ishin no Kai), the political party to which both men belong. The plan, which would unify Osaka Prefecture as a metropolis divided up into special wards similar to the current administration of Tokyo, was originally proposed by One Osaka founder Tōru Hashimoto and has been a central and divisive part of the region’s politics ever since. Hashimoto resigned from front-line politics (at least for the time being) after the plan was narrowly defeated in a referendum in Osaka City in 2015; new party leader Matsui has carried the flag for the plan since then. One Osaka claims that its plan would allow for significant cost savings and would make Osaka more competitive by centralizing planning, but the appeal of the plan also rests heavily on the symbolism of Osaka being recognized as a metropolis equal to those Edo upstarts in Tokyo and a form of regional populist rhetoric that appeals to any sense of wounded local pride.

There’s a practical reason for One Osaka to field its best-known candidates in April – its grasp on the local assemblies is tenuous.

One Osaka had originally hoped to hold another referendum on the issue by the end of 2018, but was stymied by its lack of working majorities in either the municipal assembly of Osaka City or the prefectural assembly of Osaka Prefecture. One Osaka is the largest party in both assemblies but only holds a majority with the assistance of Komeito – which opposes the Metropolitan Plan, as do every other party in the assembly. Matsui and Yoshimura have claimed that Komeito promised to support a new referendum nonetheless (Komeito denies this); they say that their resignations to seek fresh mandates from the people of Osaka are a response to Komeito’s duplicity over this supposed promise.

There’s no doubt that winning fresh terms in both the governor’s and mayor’s offices would reassert One Osaka’s political position – but there’s an even more practical reason why the party would want its two heaviest hitters (Hashimoto aside) on the field for this year’s local elections. One Osaka’s grip on the assemblies is tenuous; in both the municipal and prefectural assemblies, the LDP and Komeito need to pick up only three seats to command a majority between them. The party will be hoping that by putting the mayoral and gubernatorial elections in play, it encourages its voters to turn out in large numbers to support Matsui and Yoshimura, thus securing its positions in the assembly chambers.

It’s a calculated risk. Losing either of the major offices would be catastrophic for One Osaka’s plans – but Matsui is almost certainly a shoo-in for the mayoral race, where he’ll face LDP former assemblyman Akira Yanagimoto (who had originally been slated to run for his uncle’s House of Councillors seat in July). Yoshimura will face a more experienced candidate in former vice governor Tadakazu Konishi but remains a comfortable favourite in the gubernatorial race. On the assembly side of things, much will hinge on voters’ perception of One Osaka’s performance since it took over the governance of both the city and prefecture – and while the Osaka Metropolitan Plan will be part of that assessment, so too will the day to day running of the city under a belt-tightening financial regime that has slashed thousands of public jobs but, critics claim, done little or nothing to fix Osaka’s serious public debt burden or its shrinking business tax revenues.

The hurdle to converting Osaka into a metropolis will remain very high even if One Osaka does well in the elections.

Even if One Osaka manages to retain its position in all of the upcoming elections – retaking the mayor’s office and governorship and holding or even increasing its share of the seats in both assemblies – the Osaka Metropolitan Plan faces an uphill struggle. It’s unclear what has changed since 2015 that might result in a different result in a new Osaka City referendum and even if a new referendum could be held and won, the resulting Osaka Metropolis would be a cut-back version of Hashimoto’s original vision because Osaka Prefecture’s other major city, Sakai City, has comprehensively rejected the plan. The Metropolitan Plan may offer effective, somewhat populist rhetoric to One Osaka politicians locally – the demand that Osaka be treated equally to Tokyo has never been a vote-loser in Kansai – but its rejection by Sakai residents (who have consistently elected Metropolitan Plan opponent Osami Takeyama as mayor since 2009) hints at underlying concerns that also spill over into Osaka City. Sceptics claim that it would actually result in more tax revenues from the prefecture’s central cities being used to subsidise outlying wards, while its advantages in terms of cost savings and improving Osaka’s declining business environment remain uncertain.

Those concerns are a problem, because the hurdle One Osaka must clear to implement its plans is fairly high. Legislation passed in 2012 sets out the criteria for major cities (with over 2 million inhabitants) to effectively dissolve and merge their governance with the surrounding prefecture, creating a Tokyo-style metropolis made up of special wards; doing so requires the approval by both assembly and referendum of every participating municipality. Thus far, even after excluding Sakai City from the plan (the practical implications of which raise many question marks over implementation), One Osaka has failed to achieve majorities with either of the required assemblies or with the public. If the party wins a fresh mandate in the April 7 elections, its next step will likely be to push for a new referendum in the hope that winning a public vote will allow it to strong-arm other parties in the assembly to support “the will of the people,” a populist move that will no doubt give Brexit-watchers a sense of déjà vu.

Other major cities which are pondering changes to their legal status have been watching Osaka closely. Nagoya mayor Takashi Kawamura and Aichi governor Hideaki Ōmura floated the notion of merging the city and prefecture into a new “Central Metropolis”, Chūkyōto (中京都) in the early 2010s but the concept has barely been mentioned since Osaka’s referendum was defeated. Yokohama, meanwhile, is pushing in the other direction entirely – lobbying the central government to pass new legislation which would allow it to become a “Special Autonomous City”, with its functions entirely devolved and separated from the surrounding Kanagawa Prefecture. There’s as much emotion and symbolism involved in these drives as there is serious consideration of how best to structure local governance; but which, if any, of these efforts actually succeeds is likely to set the course for the future governance structure of an ever more urbanised Japan.

Rob Fahey is the CTO of VETA K.K., a Tokyo-based data science and survey technology startup, and an Adjunct Researcher at the Waseda University Institute for Advanced Study (WIAS). He formerly held academic roles including Assistant Professor at WIAS, Adjunct Professor at Aoyama Gakuin University's School of International Politics, Economics, and Communication, Visiting Professor at the University of Milan's School of Social and Political Sciences, and Research Associate at the Waseda Institute for Political Economy (WINPEC). He received his Ph.D from Waseda University.