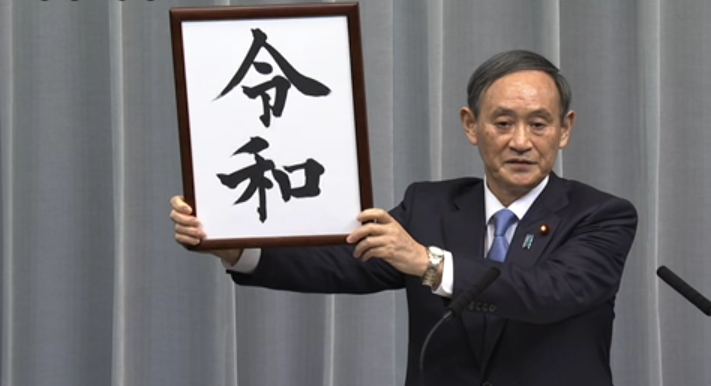

At 11.30am on April 1st, the Japanese government announced the name of Japan’s new era. In one month’s time, the Heisei era will end with the abdication of the current Emperor, Akihito, and the country will enter the 令和 reiwa era.

The new name is taken from classical Japanese literature – it appears in the Man’yōshū, the oldest known collection of Japanese poetry which dates back to the late 700s. The first character 令 rei means “command” or “decree” and has never previously been used in an era name, while the second character 和 wa meaning “harmony” or “peace” (and often used as a shorthand for Japan itself) is among the most commonly used characters in historical era names.

The meaning and intention behind the new era name will likely be a topic of discussion for scholars for some time. Prime Minister Abe focused on the Man’yōshū poem from which it is drawn in his explanation, noting that a 令月 reigetsu in this classical context referred to a fine early spring month, while 和 was used as in 和らぐ yawaragu, “to soften or abate”, referring to mild spring winds. The era name, Abe explained, expresses hope that the new era will be one in which the Japanese people thrive following a period of coldness. The inclusion of 令 rei is likely to be divisive, however, as the character is commonly found in words such as 命令 meirei (order / command) or 法令 hōrei (law, ordinance). One other possible interpretation is that the name is a nod to Japan’s constitution – “a decree for peace” – which the present administration hopes to amend in the coming years.

The importance of a new era name can be hard to grasp for those more familiar with using the Western-style CE calendar. Japan uses both calendars interchangeably – so this year is both 2019 and Heisei 31 – with many official documents in particular using the era name style. People define themselves to some extent by the era in which they were born and the change in era brings with it a sense of an end and a beginning not dissimilar to the turn of the millennium. Endless television shows and newspaper column inches have been devoted to retrospectives on the Heisei Era – a complex period of Japanese history that saw everything from major natural disasters and terror attacks by religious cults to economic stagnation and significant social change.

This is the first time that Japan has announced a new era name in advance of the beginning of that era – a practical decision which was made to allow businesses and government departments time to prepare for the change but which nonetheless stoked controversy among conservatives. The one-month delay has seemingly caused at least some confusion among citizens, with topics related to the “end of Heisei” or the “last day of Heisei” trending on social media in Japan on March 31st – though those topics were largely filled with replies pointing out that today’s event is merely an announcement, with a month of the Heisei Era still remaining.

The panel of experts charged with choosing a new era name generally delve into classical Chinese literature for their choices, but the involvement of experts in Japanese literature and history this time raised the possibility of a name drawn from a Japanese classical work. Their decision is made within a number of restrictions. Some are obvious: an era name must be two kanji characters, can not be a repeat of any previous name and should convey an auspicious, positive sense to the nation’s people. The era name also needs to be easy to read and write – no unusual character readings or obscure, complex kanji (the Asahi Shimbun reported last week that kanji with more than 12 to 15 strokes had been ruled out).

Less obvious restrictions include one related to the English version of the new era name, which should not start with M, T, S or H – the first initials of the modern era names so far (Meiji, Taisho, Showa and Heisei). Repeating one of those letters would have caused confusion as these are commonly used as shorthand for years, especially birth years – a 25-year-old might describe themselves as born in “H6”, while a 50-year-old was born in “S44” (and anyone celebrating their hundredth birthday this year was born in “T8”). The panel also needed to avoid picking kanji combinations which are already in use by companies or which are popular as given names.

In the run-up to the announcement many rumors about the new era name circulated, some of which concerned entire names – 永光 eikō (“perpetual, light”) and 安久 ankyū (“peaceful, long-lasting”, though wags were quick to point out that it could also be interpreted as “cheap forever” – perhaps not the most auspicious message for deflation-hit Japan) were both suggested in recent weeks. More credible were suggestions from experts of specific kanji characters that might find their way into an era name, with 安 an (“peaceful”) being commonly mentioned as a likely inclusion. This stoked a certain degree of controversy as it is also the first character of Prime Minister Abe’s surname, but its connection with era naming far predates his premiership, having first appeared in an era name over a thousand years ago and used as such 17 times in total.

With the new name publicly announced, attention will now turn to the accession of the new Emperor, Naruhito, which will take place on May 1st and will be celebrated in Japan with an unusually long set of Golden Week public holidays. Following a lengthy transition period, Naruhito’s actual enthronement will then take place on October 22nd.

Rob Fahey is an Assistant Professor at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study (WIAS) in Tokyo, and an Adjunct Professor at Aoyama Gakuin University's School of International Politics, Economics, and Communication. He was formerly a Visiting Professor at the University of Milan's School of Social and Political Sciences, and a Research Associate at the Waseda Institute for Political Economy (WINPEC). His research focuses on populism and polarisation, the impact of conspiracy theory beliefs on political behaviour, domestic Japanese politics, and the use of text mining and network analysis techniques for political and social analysis. He received his Masters and Ph.D from Waseda University, and his undergraduate degree from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.