Welcome to the July 2019 installment of “Sino-Japanese Review”, a monthly column that provides a running commentary on the evolution of the important relationship between China and Japan, and helps to put current events in perspective. Previous installments may be found here.

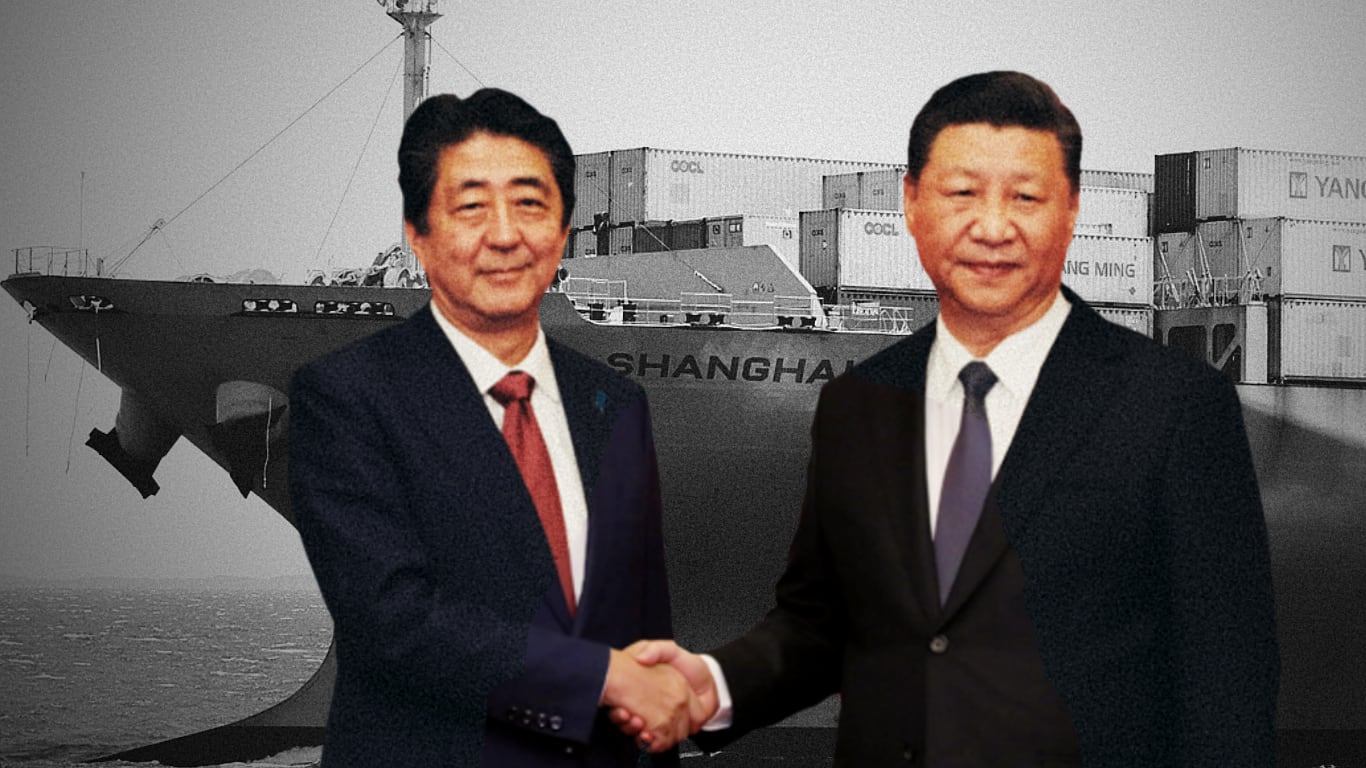

The G20 summit held in Osaka in the final days of June saw little progress in redesigning the global economic architecture, and few signs that the Trump administration is willing to ease its attack on the international order. In this unsettled context, China and Japan held their own summit meeting the day before the international gathering. This was a continuation of efforts by the two countries’ leaderships to develop their bilateral ties despite unresolved disputes around historical memories and territorial issues. In a not-so-subtle rebuke to U.S. policy, declarations of support for free trade and multilateralism figured prominently in the discussion between Abe Shinzo and Xi Jinping. This facade of unity, however, hides some quite different understandings of what is needed to improve the international economic climate.

A certain sympathy

Tokyo must certainly feel some degree of sympathy for its neighbor in its economic confrontation with Washington. To begin with, Japan itself is currently under pressure from the White House, which is demanding trade concessions and threatening to impose harmful tariffs on car imports. The much broader trade war launched by the Trump administration against China also evokes in Tokyo bad memories of the 1980s, when Japan became the target in the U.S. of the same kind of resentment and anxieties now aimed at its neighbor. The concessions Tokyo then had to make under American pressure – along with the ill-advised measures of adaptation Japanese authorities took domestically – laid the ground for the economic malaise of the following decades. This experience still smarts today.

The China Daily may thus have indeed spoken for both sides when it proclaimed, following the Osaka summit, that “as the world’s second- and third-largest economies, China’s and Japan’s pledge to safeguard multilateralism and free trade is a strong note promoting economic globalization at a time when the world is on the verge of being hijacked by the unilateralism and protectionism of the United States”. Yet even if both countries are united in their desire to defend the global open economic architecture – and to expand it further in Asia by concluding negotiations for the proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and for a prospective trilateral free trade deal with South Korea – this broad consensus masks different opinions of what is actually needed to advance economic cooperation.

Apparent consensus, hidden differences

Nothing exemplifies the difference between the two parties better than the agreement reached by Abe and Xi to create a “fair, non-discriminatory, and predictable business environment” in both countries. The Chinese side’s insistence on non-discrimination refers to demands for market access for Huawei and other technology companies, which the Japanese government has de facto decided to ban from participation in the construction of the archipelago’s 5G network. Japan’s emphasis on fairness, on the other hand, reflects the concerns it shares with other developed economies regarding forced technology transfers, poor intellectual property protection, and other problems affecting foreign companies operating in China. Adopting such a broad formulation was therefore the only way to reach some form of consensus between the two sides.

In economics as in other fields, then, the two neighbors have to tread a thin line to avoid letting various issues in dispute ruin the cooperative atmosphere that they are trying so hard to maintain. A change in external circumstances – chief among them a policy shift in the U.S. – could quickly spoil the mood. If a new American administration were to change tack and work with allies to form a united front demanding that China reform its objectionable economic practices, Tokyo would likely be more than happy to follow Washington’s lead, even at the cost of incurring Beijing’s displeasure. The Sino-Japanese entente on economic matters is thus circumstantial rather than fundamental. A desire to reap the fruits of bilateral trade and investment will continue to be one of the forces pushing the two countries to manage their differences and maintain a modicum of stability in their ties no matter what. It is, however, a long way from that shared desire to a joint economic vision that could form the basis of a more durable partnership.

Andrea A. Fischetti is a government scholar conducting research on Asia-Pacific Affairs and East Asian Security at the University of Tokyo and at the Asia Pacific Initiative. He was a visiting student at the Hiroshima Peace Institute of Hiroshima City University, and a research assistant at the House of Commons in the British Parliament. Mr. Fischetti earned his MA in War Studies from King’s College London, following a BA with First Class Honours in International Relations, Peace and Conflict Studies.

Antoine Roth is assistant professor at the Faculty of Law of Tohoku University, working on Sino-Japanese relations, China's foreign relations, and East Asian international affairs. He holds a PhD in International Politics from the University of Tokyo and a MA in Asian Studies from the George Washington University and a BA in International Relations from the University of Geneva. He has previously worked at the Swiss Embassy in Tokyo and has been a visiting student at Fudan University in Shanghai.