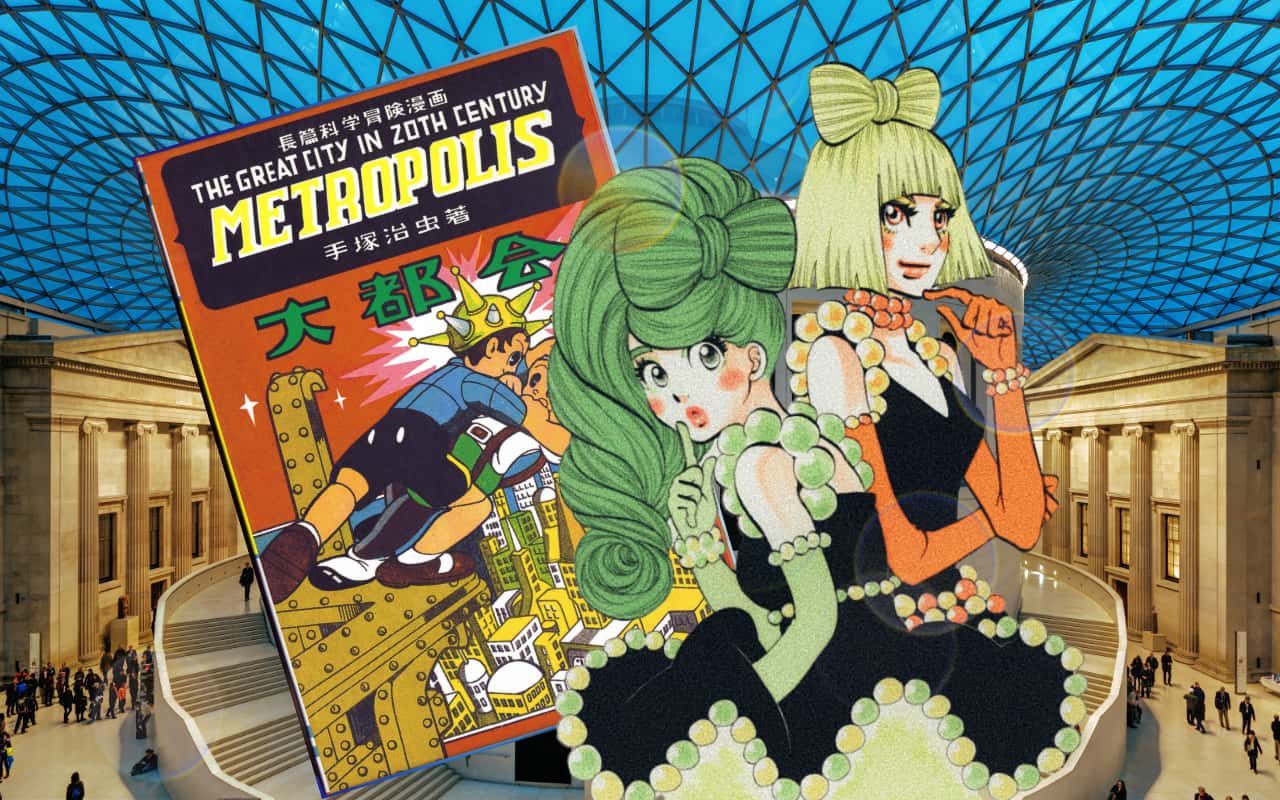

The British Museum, best known for the Rosetta Stone and recent criticism for its colonial-era acquisitions, is now temporarily home to a rotund Pikachu and Dragon Ball characters. They are visiting London as part of the Citi exhibition Manga – the largest exhibition of manga ever held outside of Japan.

The exhibit – held in the massive Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery, the museum’s largest temporary exhibition space – features stunning examples of artists such as Tezuka Osamu (Astro Boy and Princess Knight) and Oda Eiichirō, author of ONE PIECE, the highest-selling manga of all time. The show also illustrates the history and ecosystem that underpin manga, from artistic precursors to the genre, publishers, and Japan’s most important comics market and symbol of otaku culture, Comiket.

Of course, manga has been shown at other major museums before as part of other exhibits. The enormous and thoughtfully curated exhibition at the British Museum, however, should put to rest any doubts – either from people in Japan or elsewhere – about manga’s status as an art form.

The content may not be “representative”, but it highlights manga’s pushing forward of taboo topics

What is also notable about this exhibition is that there are no Japanese sponsors. The main sponsor is Citi, as part of a five-year program of support for major exhibitions at the British Museum. That is not to say there was not significant Japanese input; all of Japan’s major manga publishing houses are featured (something which the British Museum’s stance as a non-Japanese, neutral institution allowed it to achieve), and Sainsbury Institute Research Director and British Museum Japanese arts curator Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere solicited feedback from the industry in Japan on numerous occasions.

Given the international nature of its sponsors, it’s perhaps not surprising that the exhibit is presented through a modern, British/Western lens that celebrates diversity and inclusiveness. There is a 50/50 split between female and male artists and a focus on works that celebrate diversity of sexual orientation, ethnicity, and culture, along with a celebration of the Japanese art’s comfort with gender-bending themes. Given that the biggest weekly manga magazine for boys sells more than four times more than the highest selling one for girls, the content is perhaps not “representative” of the market but does serve to highlight manga’s ability to explore and push forward taboo topics.

The exhibit raises questions about Cool Japan; Japanese pop culture is well-known enough overseas to be celebrated independently

There is no graphic content – a deliberate decision, says Rousmaniere, based on weighing both considerations about the audience (the museum would have had to put graphic content in a separate room) with concerns about censorship, considering its use in silencing manga artists in the past. This decision appears to have been well-founded, especially considering that one of the largest audiences for the exhibit are children and teens. “What is so cool is that the children are teaching their parents and grandparents,” says Rousmaniere. “They are empowered.”

The unique sponsorship structure of the exhibit also raises questions over bumbling Japanese government efforts to sell Japanese pop culture overseas such as Cool Japan. Manga and Japanese pop culture are now well-known enough overseas that institutions are celebrating and innovating on them independently, just like many non-Japanese artists are also now putting their own spin on manga. It goes both ways; Japan has a lengthy and storied history of adapting, refining, and blending foreign influences into something unique, and the exhibit itself rightly highlights the satirical magazine Japan Punch (created for foreign audiences in Meiji-era Japan) and the impact of Disney on Osamu Tezuka.

“Manga is a language of the future,” says Rousmaniere. “It’s a visual language that started and developed in Japan, obviously with influences from Europe, America, and other places, but it’s a Japanese visual language, that is rapidly becoming an international language just like sushi. It’s transforming as it’s coming here, morphing into other things, but we wanted to show it in its Japanese flavor as it is now.”

The exhibition runs until August 26.

Eleanor worked for five years as a correspondent in the Tokyo bureau of The Wall Street Journal covering economy, finance and Japan's butter shortage. She is a graduate of Georgetown University, and her favorite animal is a capybara.