In recent weeks the relationship between Japan and South Korea has worsened significantly as Japan has removed South Korea from its “whitelist” of trusted export partners for certain chemicals that are vital to Korea’s high-tech industries. Japan says this move was driven by security concerns over South Korea’s enforcement of sanctions on North Korea, but South Korea (and much of the international press) views it as an escalatory retaliation for a recent court ruling forcing Mitsubishi Heavy Industries to pay compensation to Korean victims of wartime forced labor policies.

This article is an edited transcript of the Tokyo Review editors and contributors’ Slack conversation about the reasons for the sanctions – and whether there is any clear path to avoiding further escalation and repairing the relationship between two of East Asia’s most important advanced democratic nations.

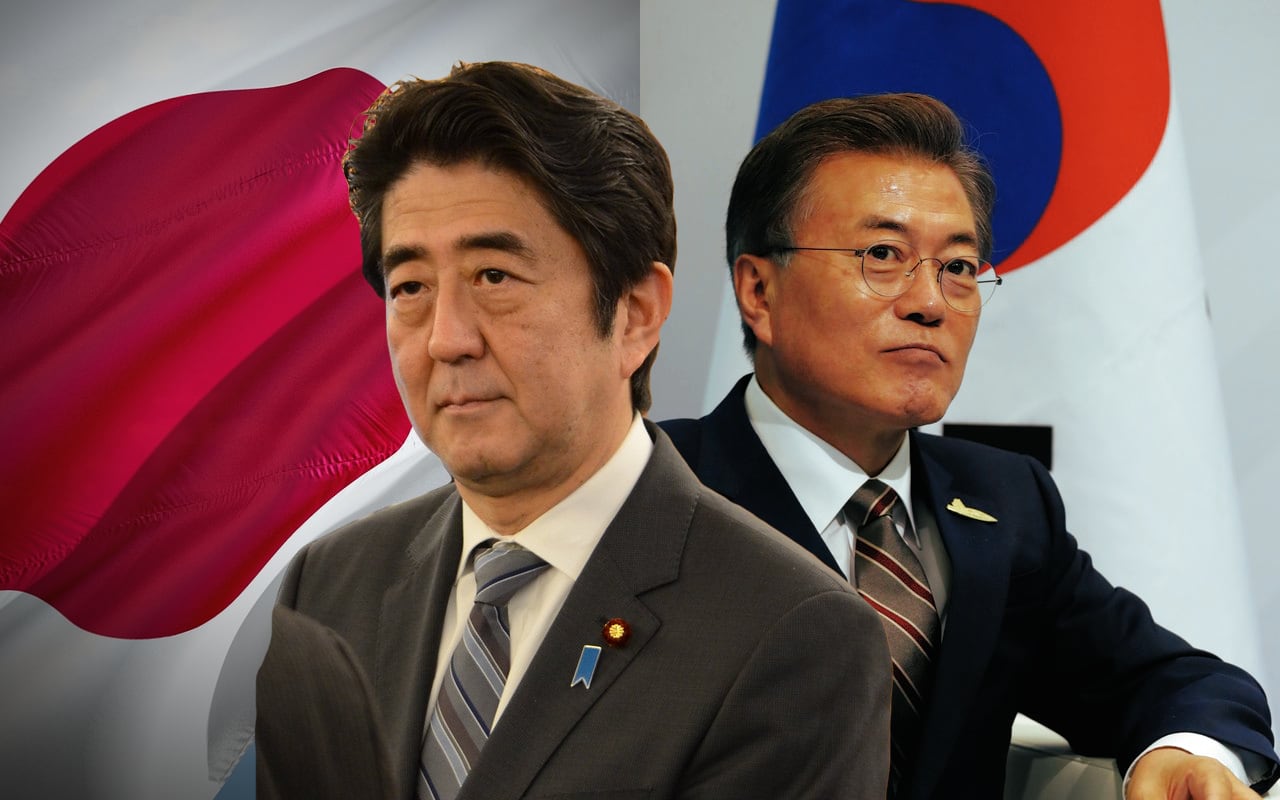

Paul Nadeau: Alright let’s get this started: Why do we think [Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō] Abe has put sanctions on Korea and why now?

Rob Fahey: I’ll bite… I think “why” and “why now” have different answers, and “why now” is arguably easier – for a start, it was ahead of an election where the only other substantive issues were pensions and consumption tax (neither of which play especially well for the LDP right now), and feelings are running high in parts of the LDP base over the forced labor court rulings so it was a good opportunity to take a hardline stance. Also, the past decade or more of formal and informal structural changes within the government and bureaucracy mean that the decision could be dictated largely from the Kantei (the Prime Minister’s office) because any concerns the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) might have over this kind of decision can now be easily overridden.

The actual “why” is more complex – the “security concerns” line being pushed by the Japanese side is being treated by the international media as entirely confected, but that’s not the case. The chemicals impacted do have military applications (including manufacture of sarin gas, which Japan is pretty touchy about for obvious reasons) and there are ministry officials in Tokyo who genuinely think South Korea is being naïve and incautious in the way it’s handling the relationship with North Korea right now, and may not be a reliable partner in enforcing sanctions on this kind of material.

However, that matter is something that would in the past have been handled quietly, possibly in a trilateral way involving the United States. A combination of the United States being pretty much out of the picture in current geopolitical developments here, plus the “why now” factors above, have instead turned the whole thing into a giant, messy public squabble with serious potential economic and security implications.

“Having the U.S. out of the picture has helped turn the whole thing into a giant, messy public squabble with serious potential economic and security implications”

PN: I’m not totally sold on the election angle… The gains to a hardline approach on this issue are marginal compared to the foot-stomping that would come out of the business community. I also would have imagined that Abe’s approach would have included an off-ramp to defuse the crisis once the election was over.

Obviously that would have been nakedly opportunistic but also basically in character. And maybe they had envisioned an off-ramp but (South Korean President) Moon Jae-in was more stubborn than they expected which caught them off guard. I don’t usually give Abe much credit on issues with Korea but I can’t imagine him being obtuse enough to fail to imagine that Korea might react strongly to something Japan would do on something like this.

The METI role is curious though – the Nikkei piece on the dispute said that METI took an active role in drafting the proposals when most of what I’ve heard (and we’ve discussed at least) is that METI is furious at being sidelined by the Kantei… so I wonder if there’s a backstory here.

That said, I could imagine the government of Japan thinking that there are legit national security concerns with ROK’s handling of the chemicals and wanting to sanction them accordingly and then being taken aback when South Korea doesn’t see the sanctioning as simply a narrow technical issue.

RF: I think there are probably mixed messages coming out of the business community on this – sure, some of them especially in semiconductor-related fields are angry at the potential for lost business and at potentially facing new competitors in a few years as the South Korean government supports companies building up supply chains that bypass Japan, but I don’t know how loudly that message would reach the top of the government compared to the white-hot fury of the big old keiretsu at the prospect of the South Korean government seizing and liquidating their assets over wartime-era labor claims.

PN: That’s a good point – the claims could be huge.

RF: And the companies affected are not nimble – most have physical assets in South Korea that they can’t move or liquidate easily. If the courts there decide to start awarding judgements en masse, it could be absolutely drastic for them

Jonathan Soble: Apparently Japan had been pushing the Koreans to address the security concerns for a couple of years. So it didn’t just pull that stuff out off a hat. Definitely more of a “why now” question, I’d say.

PN: Maybe it’s a confluence – concern about reparations and irritation at ROK behavior (radar lock, court cases, withdrawing from Comfort Women agreement)?

RF: As for the METI role in drafting, I can imagine a hypothetical where this is a case of “we drew up a set of options for handling the security issues if they came to a head – we didn’t expect the Kantei to come in, grab a particularly drastic option, implement it and then say it was our idea.”

“It’s likely Abe has had more than one golf game with a senior executive from a big industrial firm who pointed out a list of assets Korea could seize if the court cases proceed”

As Jonathan says the security issues (and probably these proposals) predate the current political situation but all those things (Comfort Women deal, reparations etc., plus a general sense of South Korea decoupling from allies in its dealings with NK) help to explain the “why now.”

I imagine Abe had more than one golf game with a senior executive from a big industrial firm who pointed out a laundry list of assets Korea could seize and liquidate if the reparations court cases proceed – so yes, the election may be one factor but pressure from business to “do something” was likely a bigger one.

PN: That makes sense since it bridges Abe’s nationalist instincts with the practical concerns of keeping business happy. That said… I wonder what kind of reaction Abe was expecting from ROK. They had to know it wouldn’t be good, but I could still see the Japanese government being taken aback by the massive boycotts and self-immolation. It’s not as dramatic as opening fire on a nuclear superpower over a disputed territory, but still.

If I wanted to be cynical, I’d say Moon saw an opportunity to leverage domestic nationalism to boost his support – and it’s worked.

RF: If the Japanese government is taken aback by this, the Japanese government hasn’t been paying attention… more likely they simply don’t care much about the reaction. That should come as a surprise to precisely nobody; it’s a big part of the reason why they’re often bad at handling these issues.

PN: So we’ve got the unstoppable force of Japanese keiretsu terrified of asset seizures against the immovable object of Korean historical grievances… I’m skeptical there’s an off-ramp to that.

RF: I agree. I think the only off-ramp here has to start with a (very unlikely) Japanese climb-down, because what they’re asking South Korea to do is actually pretty enormous politically – spitballing a little here, but the legislature would probably have to draft and pass a new law effectively protecting Japanese companies’ assets from court seizure in these cases. Given the domestic climate right now that would cost more political capital than anyone, including Moon, actually has, even if they wanted to do it in the first place. Relations have to normalize to the point of being downright cozy before that even becomes an option for Korea – further escalation will only be matched from the other side, because Moon and his administration don’t really have a move they can play that effectively backs down from this.

JS: This is one area where the United States could have helped if the Trump administration weren’t so disengaged. Not solving the problem, or even necessarily playing an active role – just being there to give the two sides a face-saving way out. “We wanted to fight, but the Americans forced us to make nice.” Generally, having the United States in the picture allows Japan and Korea to say nasty things to each other without having to follow through in ways that cause serious damage. That’s not exactly an ideal relationship – it would be better, arguably, if Japan and Korea had to take full responsibility for their rhetoric in the first place. But for now, at least, U.S. disengagement is removing the guardrails before the drivers have learned to drive more carefully.

“Having the United States in the picture allows Japan and Korea to say nasty things to each other without having to follow through in ways that cause serious damage”

PN: And Japan will never consider an update or replacement for the 1965 treaty because they (fair or not) don’t trust Korea to respect any agreement given how they feel the existing agreement (and others) have been treated by Korea.

RF: Thing is, I think that’s a position a lot of international opinion would be sympathetic to – “look, we did a treaty that included a form of reparations back in 1965, now they’re saying 54 years later that it’s not sufficient; but when we tried to do something extra in 2015, they tore that up within a few years too.” Japan’s actually got a pretty solid public opinion case on the fundamentals here – making it a next-level bit of diplomatic incompetence that they’ve managed to treat the whole thing so heavy-handedly that to most of the world they presently look like a straight-up villain that’s taking a leaf from the Trump playbook on trade. They’re not either of those things – they’re not the black-and-white villain of the piece, nor are they really copying Trump’s strategies – but that’s exactly the simplified picture the rest of the world is getting, and much of the blame for that lies with Japan’s poor management of the narrative.

If there’s a route through this it’s going to have to start with a Japanese climb-down over the export restrictions etc., some dull procedural business-as-usual working group stuff on security concerns (addressing Japan’s claimed concerns and starting to restore the allies-working-together image of the whole relationship), and some kind of tacit agreement to make best efforts on both sides to maintain the previous status quo.

But honestly, I think the genie is out of the bottle at this point, because the Korean court proceedings are going to keep rolling inexorably onwards and Japan is never going to be willing to tolerate what it views as illegal appropriation of Japanese industries’ assets.

“The genie is out of the bottle at this point”

PN: Right – but Japan already lost its case when the headlines started screaming about embargoes and using trade policy as a political weapon when what removal from the whitelist actually means is that they have concerns about the relevant party’s export controls and those processes are under review. It’s nowhere near as dramatic as Trump’s demand that auto imports are a national security threat and it shouldn’t (on its own) have the same implications. But the Kantei began its relationship with the Moon Jae-in administration with some built-in biases about the Korean left, thought that those biases were confirmed with the withdrawal from the Comfort Women Agreement, radar lock debacle, and others, and decided to push back using a narrow technical tool.

That’s basically that paradox for Japan – objectively they may be right about their concerns over exports and the Korean government’s handling of past agreements, but it’s impossible to consider the Kantei’s steps separate from their biases toward Korea and their belief that they’re finally going to put them in their place. There’s some legitimacy to their objective case but they have absolutely no credibility because they’ve overreacted so ham-fistedly to every noise coming out of the Korean government that so much as touches on history.

“It’s impossible to consider the Kantei’s steps separate from their belief that they’re finally going to put Korea in its place”

I also don’t think people realize how dramatic the implications might be for the Korean courts to demand redress to the former laborers. If there’s a precedent that individuals can make claims for harm during colonial occupation, then… Let’s just say Brexit will be the least of Britain’s problems.

There’s also the fact that successor regimes usually inherit the treaty agreements of their predecessors unless they explicitly say otherwise, so while Park Chung-hee might have been a collaborationist authoritarian [redacted], modern ROK is still stuck with the treaty unless they agree with Japan to negotiate a new one.

RF: The part about Japan completely losing the headlines despite having significant validity in their claims is basically the cliff’s notes for thirty years of incompetent management of the public relations and narrative side of this whole issue. On the one hand you’ve got Japan’s insistence that despite all the emotive and political issues, on the core decision they’re technically right which is the best kind of right, and no other considerations should be entertained – a brutally unsympathetic position for a powerful nation to take – and on the other hand you have their inability to manage any kind of relationship with the international press, which South Korea has become very, very good at.

The fact that there are still senior decision makers in Japan – both politicians and bureaucrats – who cut their teeth when Korea was an autocratic basket case of little international relevance probably doesn’t help. They seem to lack the mental flexibility to adapt to strategies in a world where much of the international audience sees South Korea both as Japan’s contemporary equal and former victim – everything they come up with is condescending, dismissive or worse, which weakens Japan’s position even in cases where South Korea is the party stoking anger and provoking incidents. This kind of attitude isn’t exactly unusual in former colonial relationships – see the absolute conviction of many parts of the UK establishment that Ireland should/would just “get in line” over Brexit, and their dumbfounded outrage at Ireland instead continuing to act in its own best interests – almost like some kind of independent country! – the political situation is completely different of course, but the parallels in terms of attitudes are clear.

Paul Nadeau is an adjunct assistant professor at Temple University's Japan campus, a visiting research fellow at the Institute of Geoeconomics, and an adjunct fellow with the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He was previously a private secretary with the Japanese Diet and as a member of the foreign affairs and trade staff of Senator Olympia Snowe. He holds a B.A. from the George Washington University, an M.A. in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University, and a PhD from the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Public Policy. He should be general manager of the Montreal Canadiens.