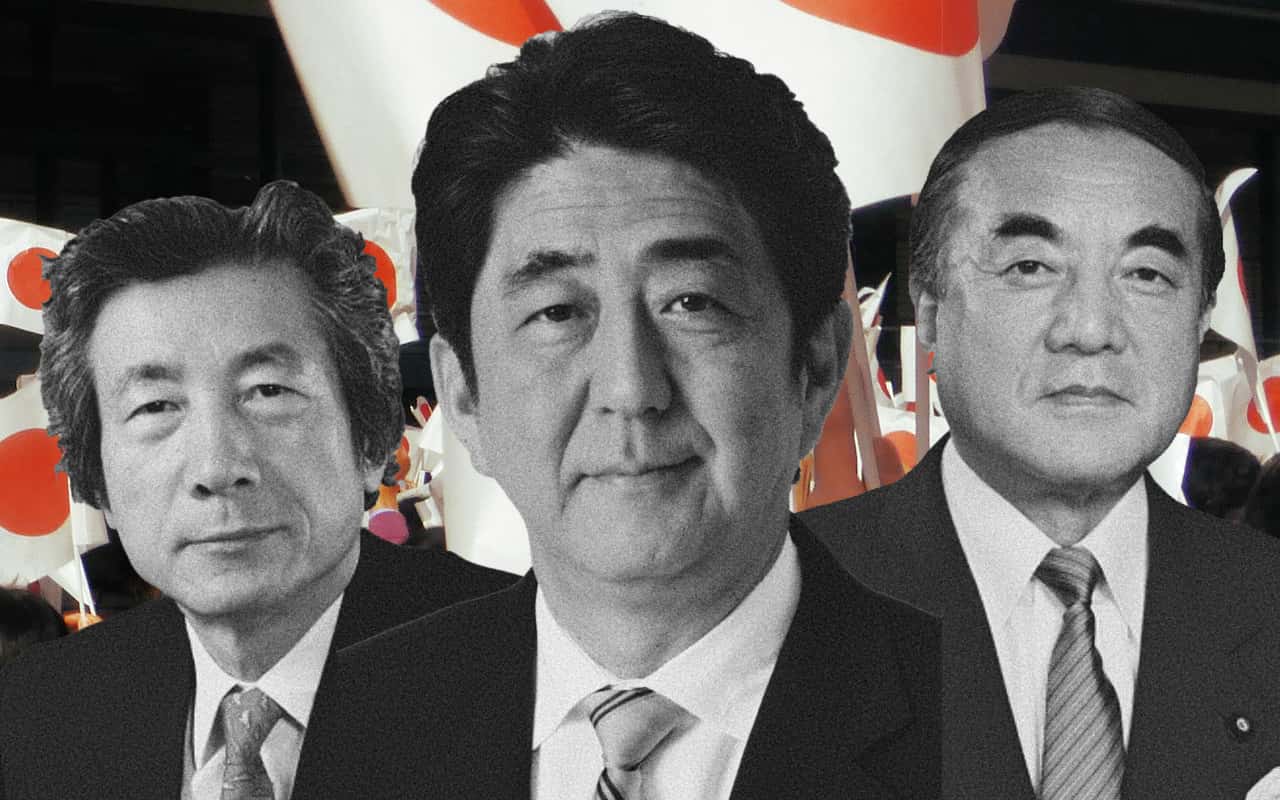

Describing Japan’s neoconservatives – figures like Koizumi Junichiro and Abe Shinzo who want Japan to be unfettered by its postwar experience – to a Western audience is tricky. The word “neoconservative” itself immediately conjures up Bush-era American decision makers like Dick Cheney, Paul Wolfowitz or John Bolton who took the lead in pushing for war in Iraq to overthrow Saddam Hussein and remake the country with American political traditions. The influence of these individuals was so great and their work so infamous that the word is now toxic, such that applying it to political actors in another context like Japan is immediately controversial. Moreover, for all that Japanese and American neocons have in common, there are important differences – including the fact that Japan’s neocons have been restrained in their efforts in ways that would have made their American counterparts chafe. As a result, Japan’s neocons have made a lot of noise but have accomplished far less than those in the United States.

The similarities in the worldviews of these two groups, however, merit the application of a common label. Just as America’s neocons originated as a reaction to rising liberalism at home and a sense that “dovishness” had overtaken American foreign policy after the end of the Vietnam War, those in Japan originated as a reaction against Japan’s own political liberalism and demilitarization. Both American and Japanese neocons believe that “strong will” is the critical factor to answering security challenges and both believe that loss of purpose and weakened moral fiber have made such challenges exponentially worse, to the point of putting their country at risk.

There are also significant differences. American neocons are civic nationalists and marry their idealism with a consequentialism that permits just about anything – not least of all military force – towards achieving their messianic vision of American values as the only acceptable order in the world. Strictly speaking, the word has often been misapplied – historically the term referred to those in the 1960s and 1970s who became disillusioned with the Democratic Party’s apparent pacifism and accommodation with the communist bloc and preferred a more muscular, hawkish, and uncompromising approach to dealing with the Soviet threat. This distinguishes orthodox intellectual neocons like Jeanne Kirkpatrick and Richard Perle from more conventional hawks like Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld who were never strictly part of the movement but still glad to use their ideas as an intellectual patina.

Japan’s neocons, like Britain’s “High Tories”, seek to restore the country’s standing by resurrecting traditions from an imagined past.

Japan’s neocons, on the other hand, are restorationists, closer to Britain’s traditionalist “High Tories,” resurrecting former traditions from an imagined past. They are determined to restore Japan’s national standing, end its chastised military posture, restore “traditional” values, and so on. Their disputes over historical issues with China and Korea become clearer as a result – accusations of military and colonial atrocities aren’t just uncomfortable, but directly deny neocons’ idealized image of Japan’s past prior to the American occupation.

American neocons are agnostic about traditional morality and even towards the role of state nationalism (aside from military power and republican ideals), both of which Japanese neocons value highly. American neocons are opportunists, willing to work with either party that’s willing to put their ambitions into force. Japanese neocons are defined by their antagonism towards Japan’s pacifist left and see it as an existential threat to the country.

Functionally, the differences are even greater. While to American neoconservatives international institutions and international law are only capital to be exploited towards their moral ends, discarding them as soon as they begin to constrain U.S. ambitions, Abe has consistently relied on both in situations such as Japan’s response to the dispute with China over the Senkaku Islands in 2012, the response to Trump’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and World Trade Organization disputes with Japan’s trading partners – for Abe, presenting Japan as democratic and law-abiding still matters. John Nilsson-Wright and Fujiwara Kiichi have gone so far as to describe the Abe Doctrine as a “major change in Japan’s foreign policy priorities….Abe’s astute stress on [liberal] values has the advantage of placing Japan firmly in the camp of internationalist legitimacy.” Where American neocons and their intellectual partisans among America’s current China hawks seek to counter China’s rise through tariffs and military buildup, Abe has aimed to provide political support and legitimacy to the liberal international order – hardly a means or an end that American neocons would endorse.

A combination of public sentiment and institutional pressure significantly tempers the ambitions of Japan’s neocons.

For Japanese decision makers, ideological impulses are almost always ancillary to solving policy problems. That’s not to say that ideologues don’t exist among Japan’s decision makers – they do – but a combination of public sentiment, institutional pressure, and self-restraint usually tempers their boldest ambitions, including their desire for constitutional revision. Like Nakasone Yasuhiro, another conservative whose ambitions included Japan’s remilitarization, Abe’s political program has been far more modest than his ambitions would indicate. Like Abe’s approach of legitimizing Japan’s status as a global power through international law, Nakasone attempted to use legal and technical means to legitimize his visits to Yasukuni Shrine, arguing that by going in a personal capacity rather than making official visits as prime minister he was both maintaining the spirit of Article 20 of Japan’s constitution (separating religion from the state) and depoliticizing the visit. Koizumi and Abe, meanwhile, have been Japan’s longest serving prime ministers since the end of the Cold War and held significant political capital, but neither has succeeded in endearing any aspect of the neoconservative program – whether it be revision, a more active military, or traditionalist morality – among the general public – who in fact, may even be increasingly progressive.

While some notable American neocons have opportunistically worked their way into the Trump administration, Japan’s neocons may be facing an expiry date to their influence in government. In the short term, there is no one viable to carry the neoconservative nationalist banner after Abe steps down at the end of his current term. Abe himself has left no apparent successor to carry on his legacy, with all of the floated possibilities being either discredited (Inada Tomomi), not quite right for the task (Suga Yoshihide, Seko Hiroshige), or lacking political capital (Hagiuda Koichi). Motegi Toshimitsu, minister of foreign affairs, may yet demonstrate his credentials, but for now still ranks far behind succession possibilities from the rest of the LDP field like Kishida Fumio or Kono Taro. None of the viable successors to Abe match his ideological background or ambition; Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko would come closest, but she’s no longer in the LDP and highly unlikely to return. In the long run, the neoconservative failure may not just be its inability to achieve constitutional revision, but that it made absolutely no progress in growing the audience for their ideas. It would seem that Japan’s neoconservative moment was only passing.

That very failure, however, may yet be how this movement survives – and regains its force. Koizumi and Abe, as Japan’s two most unabashedly neoconservative prime ministers, were able to keep the country’s nationalists placated and at bay. They either had no need to demonstrate their nationalist credentials or were able to offer just enough, either through cabinet appointments or promises of constitutional revision, to keep more extreme elements of their base on side. As Michael Cucek has pointed out, Japan’s nationalists remain committed to Abe despite how little he has actually given them – while constitutional revision is almost completely off the table, every time Abe promises it the reaction is “Fool me once, shame on me; fool me 378 times, maybe conditions will finally be right for the 379th time” (a mistake that many of Abe’s critics also fall for, unintentionally allowing him to burnish his conservative credentials by suggesting to the nationalist base that he’s standing up to the opposition even as he gives that base nothing concrete).

Abe has placated his nationalist base despite accomplishing little on their behalf; his successor may not have that luxury.

Whoever succeeds Abe may not have that luxury with Japan’s far right. One effect of the Democratic Party of Japan’s rule from 2009-2012 was that conservative nationalists like Japan’s neocons trained their fire at the ruling party for being “too weak” on China during the Senkaku Islands crisis – which in turn created a political opportunity for Ishihara Shintaro, Tokyo’s nationalist governor, to purchase the islands, creating a cascading effect that intensified the crisis. If any successor to Abe demonstrates “weakness” towards China or North Korea, it will create ideal conditions for Japan’s neocons to find their voice and seek agency.

Whether they can actually find that agency is an open question. On one hand, the centralization of decision-making authority in the prime minister’s office has reduced the potential for bureaucrats and other stakeholders to constrain a future prime minister who has hawkish attitudes and the initiative to follow through. On the other hand, it’s hard to imagine where such a figure might emerge from. No such politician seems likely to succeed Abe and there are few rising stars in the LDP or elsewhere with similar instincts. Meanwhile Japanese voters reward competence and punish incompetence, voting on valence issues rather than along the ideological lines that might propel future neocons to office – Koizumi and Abe rose to office because of “pocketbook concerns,” rather than because of public belief in their foreign policy program. While the Japanese public is clearly unsettled by China, if not outright worried, this concern is translated into greater concern for self-defense rather than aggression. Most Japanese, especially younger ones, also don’t share the neocons’ reverence for traditional values or exaltation of the state. Politically, Japan’s neocons – despite their noise – are becoming as much of an historical artefact as their ideas.

Paul Nadeau is an adjunct assistant professor at Temple University's Japan campus, a visiting research fellow at the Institute of Geoeconomics, and an adjunct fellow with the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He was previously a private secretary with the Japanese Diet and as a member of the foreign affairs and trade staff of Senator Olympia Snowe. He holds a B.A. from the George Washington University, an M.A. in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University, and a PhD from the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Public Policy. He should be general manager of the Montreal Canadiens.