The opening of a research commission on Japan’s constitution during the ongoing special Diet session has once again raised the question of the opposition’s role in such discussions. So far, major opposition parties have stuck to their existing line, advising prudence, conservatism, and the need for more discussion before any proposal can be put before the people. But is this the most effective role the opposition can play in the process? The question may not be whether the opposition can successfully defend against a push to revise the constitution, but rather whether it has an opportunity to seize upon the revision debate as a way to make good on some of its rhetoric and make tangible progress for its constituents.

To date, the debate on revision has given the opposition bargaining power that they usually lack in the Diet, with the result being that they have played a defensive and reactive role throughout much of the current Abe administration. While that has produced some limited successes in recent years, what the opposition needs most of all – especially if it is to remain relevant beyond the Abe administration – is to show political leadership.

For this, it must strive for concrete results, especially on issues important to its supporters such as civil rights and the curtailment of executive power. Same-sex marriage and other demands from the LGBTQ community, for example, featured prominently in opposition campaign rhetoric in recent year but has had little overall effect on the ruling parties’ views, and Abe’s characteristic heavy-handedness point to structural potholes that could be filled by parties more concerned with constitutional issues. The progressive opposition parties have drawn stable but middling support from citizens concerned with such issues, but it is time they built trust in both their character and competence to grow their base more substantially. Active participation in the revision debate could allow the opposition to move beyond rhetoric and start delivering results.

If the opposition is to remain relevant beyond the Abe administration, it will need to show political leadership

The referendum law which was one of the only legislative accomplishments of Abe Shinzo’s 2007 administration means that any proposal that passes through the Diet (requiring a two-thirds majority in both houses) must be put to a referendum within six months. The difficulty for passing the requisite public referendum on a topic still so skewed against Abe’s preferable outcome places the opposition in an ideal spot for taking a chance on seeking true bipartisan agreement. Granted, it is not unimaginable that the LDP would try to go it alone, devising its own revision bill and relying only on votes from the ruling coalition and its allies to pass it through the Diet. Such an approach would arguably undermine its chances in a referendum, however, as opposition parties would rally against it to deny Abe his victory – and there are good reasons to suspect that the opposition line would command a plurality of votes in such a case. The need for some degree of bipartisanship to ensure success in the referendum, then, gives the opposition significant power to dictate the terms of the debate.

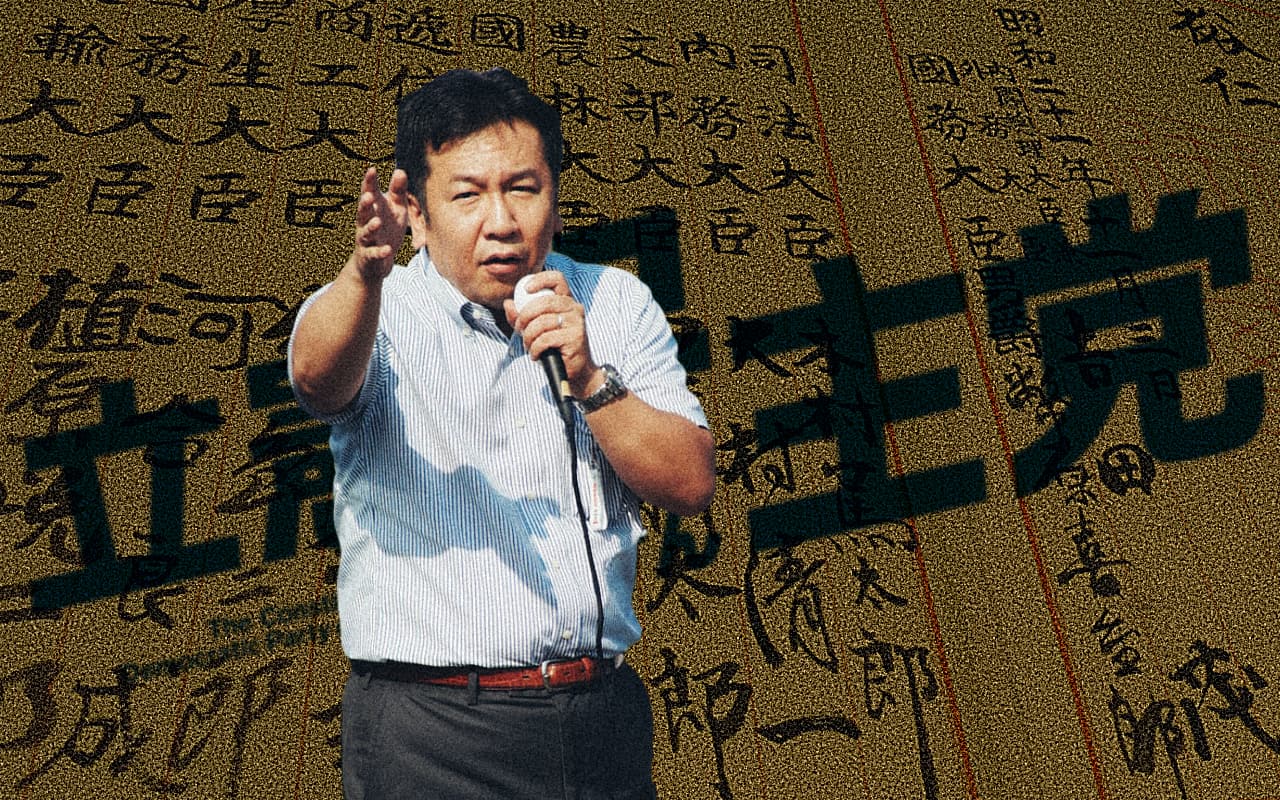

Why then have they not made use of that power to push through their own policies? When pressed on this in an interview with scholar and essayist Nakajima Takeshi, Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ) leader Edano Yukio implied that the opposition’s concern is currently related less to the sanctity of the constitution and is more about a lack of trust in the current government – especially in terms of its lack of clear procedural rigor and the unsatisfactory answers given during Diet questioning. In contrast, Edano pointed to his involvement in the 2005 report on the Nakayama constitutional research commission which he noted as an exemplary display of how dissenting viewpoints from different parties ought to be taken into account.

There are indeed practical reasons for the opposition’s conservatism on revision, but it also cannot be ignored that stonewalling on the debate pushes the LDP further into a partisan-driven approach. A vehemently anti-Abe stance galvanized the opposition to look past many of its differences at the cost of immobility in the face of a proactive government. Their gambit has sustained them so far but it is unclear if their defiance of Abe will continue to pay off dividends after he’s gone. There is no way to know in advance, but it’s a difficult bet to wager so much on someone who will shortly be off the stage when new routes can be embarked upon in the present.

The opposition would be better served by finding a proactive and unified stance rather than continued defiance of a lame duck prime minister

Rather than blindly hoping that things will turn out for the best once Abe is gone, the opposition would be better served by finding a proactive and unified stance that can help their image and cooperative strategies right now. Firstly, the opposition has prided itself in recent years on representing diversity, at least in its rhetoric and proposed policies. Soon the steady gains being made through local action regarding same-sex partnerships across the country will desperately need the kind of national backing that only a change to the constitution could ultimately realize. If the opposition takes up battles such as this in such a way as to link themselves with their realization in the near future, it will help them to break through apathy and build a more robust voting coalition.

This kind of approach need not conflict with the opposition’s policy to protect the pacifist Article 9. Not every change to this article is necessarily considered anathema; there are ways to go about it that could suit the needs of different parties. A limited revision, simply confirming the constitutionality of the Self Defense Force, for example, could be palatable to opposition supporters while also suiting Abe and more moderate pro-reform groups within the LDP. In short, the space for maneuvering without endangering the opposition parties’ core values may be much larger than it appears.

This can still be a successful strategy even if revision does not happen immediately if the opposition’s engagement with the issue now will keep them from being sidelined in future discussions. Currently, the LDP has full reign to discuss which particular version of revision to pursue, and it is heavily skewed towards whatever the prime minister deems most preferable. A vision with more diverse ideas would change the discourse well into the future and lay the groundwork for the opposition to actively protect constitutionality (as distinct from sanctifying the document of the constitution itself) if and when another push towards revision occurs.

Whether Prime Minister Abe’s last-minute rush for revision happens or not, the ball is already rolling – and a large number of the representatives of Japan’s voters remain on the sidelines. Far from being a concession, injecting a progressive voice into the debate and using the opposition’s position as a bargaining chip will start to rebuild cross-party ties and give opposition parties the opportunity to put their vision to the test. It is not without risks, but considering what can be won on priorities like civil rights and limitations on executive power, the opposition must carefully consider to what extent its current conservatism is really the best position to take when so many voters are depending on them to secure their futures.

Romeo Marcantuoni is a PhD student at the Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies at Waseda University. He earned his MA and BA in Japanese Studies at KU Leuven, Belgium. His research centers on Japan's progressive parties.