The Japan-South Korea reconciliation process continues to be hindered by the same three mistakes: a lack of victims’ voices, a lack of ambition, and a lack of long-term commitment. Several agreements, the first dating back to 1965, have failed to sustain positive relations between the two democracies. Only half a year ago, Japan and South Korea entered a costly trade war and considered ending the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA). According to a poll conducted before this latest spat, of those holding a negative view of the other side, approximately half of Japanese and three-quarters of Koreans do so because of the “history issue.”

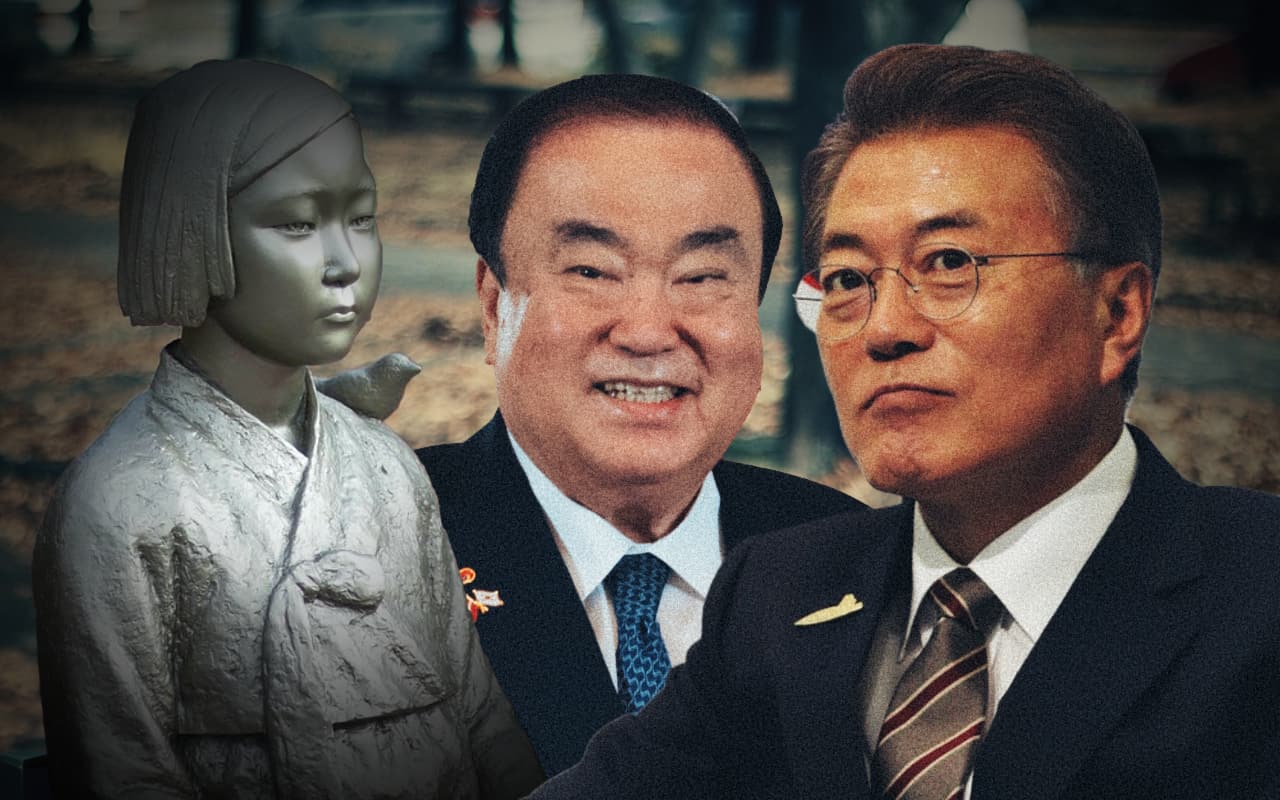

The “Memory ⋅ Reconciliation ⋅ Future Foundation Act” proposed by South Korea’s National Assembly Speaker Moon Hee-sang – the same Moon who was forced to apologize for demanding the Japanese emperor apologize to comfort women – is the most recent attempt to settle the legacy of Japanese colonization. The bill proposes that private corporations in South Korea and Japan would contribute to a foundation to pay victims of forced labor in accordance with the November 2018 South Korea Supreme Court rulings. It is likely to do little to improve relations between Japan and South Korea, far less settle the legacy of WWII finally or irreversibly.

Since relations between the two countries were normalized in the 1965 Treaty of Basic Relations, Japan has issued dozens of apologies and several agreements have been passed to address its wartime atrocities, most notably the 1993 Kono Statement, 1995 Asian Women’s Fund (AWF), 1995 Murayama Statement, and 2015 Comfort Women Agreement. The Memory ⋅ Reconciliation ⋅ Future Foundation Act repeats the same mistakes that not only prevented the 1995 AWF and 2015 Comfort Women from settling the “history problem” but will likely lead to the same backlash among both the publics of both nations once it fails.

The primary public complaint about the 2015 agreement was the lack of representation of comfort women; the new proposed bill repeats this mistake

First, the bill does not include forced laborers in the establishment or operation of the foundation. As outlined in a Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs report, the primary complaint of the public concerning the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement was the lack of representation of comfort women at the negotiating table. Immediately after the 2015 Agreement came into force, Koreans took to the streets in protest, and despondent comfort women in media-filled rooms railed at government officials for ignoring their voices. The new proposed bill has similarly been submitted to the Korean parliament without input from civil society. Moreover, the bill seeks to silence the voices of victims, who would give up their right to litigation if they accept a payout from the foundation. The proposed fund effectively splits the voice of around 1,000 victims involved in or planning to take legal action.

Second, like the 1995 AWF, funding for the foundation will be on a voluntary basis from public and private corporations. One of the main criticisms of the 1995 AWF was that it was not financed by Japanese taxes, and thus, could not be considered official compensation. Although donations may be a good reflection of what Japanese society today believes, by allowing and encouraging South Korean corporations and civilians to voluntarily donate as well, the bill removes the direct historical responsibility of the Japanese government and corporations from the reconciliation process.

Third, the Memory ⋅ Reconciliation ⋅ Future Foundation Act is billed as a “catch-all” proposal that will address all the issues concerning Japan’s wartime atrocities through financial compensation. The Korean public was furious at the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement because it sought to settle one single issue “finally” and “irreversibly.” One can expect a stronger reaction when it is the Korean government that is using similar language. In a poll conducted immediately after the act was announced, the majority of the South Korean public opposed the bill in every age group except for respondents over 60. According to a poll run by the Korea Institute of Research (commissioned by Moon Hee-sang’s office), 82.3% of South Korean citizens did not believe that Japanese companies would step up and provide the funds.

From Japan’s side, there is little incentive to reach an agreement that the other side can simply abandon so quickly

Government leaders have failed in the reconciliation process due to a combination of personal failings and circumstances beyond their control. Both governments have inherited decades of failed treaties and ineffectual apologies and face significant pressure to “win,” which may not actually involve an agreement or reconciliation. Yet, their solutions continue to be elite-driven, non-transparent, and short-sighted.

Following the collapse of the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement, “apology fatigue” was at an all-time high in Japan. There are no incentives to come to an agreement if the other side can choose to abandon the resulting agreement after less than a year. The legacies of WWII can only be addressed in an education-based and future-oriented agreement that includes victims at the negotiating table.

Moreover, inter-generational trauma requires solutions that last well beyond the date where foundation funds run dry. Beyond financial compensation, the governments should establish a foundation to educate the public on the decades-long reconciliation process that has been costly for both sides. This would mean Japan should offer a grand gesture to show remorse, possibly a memorial of its own acknowledging the victims – while for South Korea, it requires a reevaluation of the homespun narrative that Japan has never issued a “genuine” apology and an acceptance that it too has played a significant role in failing to come to terms with the past.

Tom Le is an associate professor of politics at Pomona College and research associate at the PRIME Institute at Meiji Gakuin University. Le is the author of Japan’s Aging Peace: Pacifism and Militarism in the Twenty-First Century (Columbia University Press, June 2021). Le received a Ph.D. in political science from the University of California Irvine and BAs in history and political science from the University of California Davis. He is currently a USLP delegate, Mansfield US-Japan Network for the Future fellow, and Mansfield-Luce Asia Scholars fellow.

Daphne is a senior at Pomona College majoring in International Relations with an Economics minor. She studies East Asian security issues with a socioeconomic lens, and has published works in Diplomatic Courier, The Korea Times, and International Policy Digest.