Among the many consequences of the coronavirus outbreak in China may be the deferment of Xi Jinping’s state visit to Japan, which was due to take place in early April. Preparatory talks planned for this month have already been delayed. In fact, the timing of the visit is not the only uncertainty and holding these talks will be necessary to hash out the remaining points of contention. In Japan, voices within the ruling party are questioning the wisdom of inviting Xi in the first place, considering China’s growing challenge to Japan’s control of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and ongoing concerns about human rights violations in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. Why, they ask, should the Chinese head of state be welcomed as a honored guest when his party is taking a direction inimical to Japanese interests and values? Even the Japanese Communist Party, traditionally friendly to Beijing, recently adopted a new party platform condemning Chinese “hegemonism.”

Tokyo nevertheless remains committed to the state visit – as of February 28 the Japanese government insists the visit will proceed as originally planned – and there is little doubt that it will happen at some point this year. Yet Prime Minister Abe Shinzo has also emphasized how forcefully he raised Japanese concerns about the Senkaku/Diaoyu, human rights, and the detention of several Japanese citizens on charges of espionage, during a visit to Beijing in late December. His government is thus blowing hot and cold at the same time, showing little restraint in its criticism of Chinese behavior while also stressing the importance of fostering dialogue between the two sides and of working together on issues of common concerns. This ambivalent attitude is part of what a Nikkei journalist calls the “mind games” played by Tokyo to wrangle concessions out of Beijing in order to ensure a smooth visit for Xi.

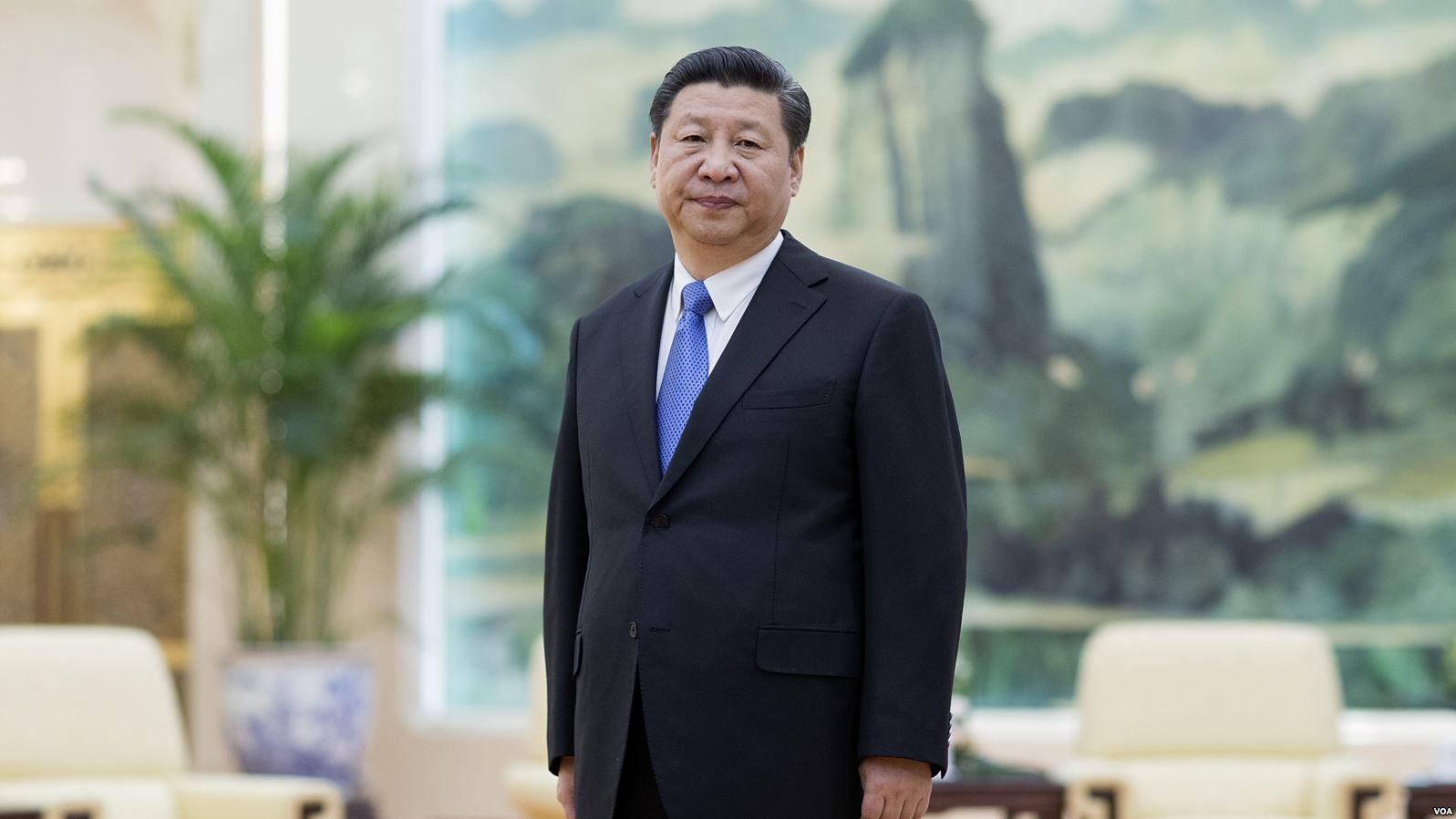

Abe is showing little restraint in his criticism of Chinese behavior while also stressing the importance of working together

At the center of discussions is the content of the so-called “fifth political document” that the two leaders are expected to unveil during the upcoming visit. It is supposed to succeed four previous ones – agreed upon in 1972, 1978, 1998 and 2008 – and to lay the foundation for the next decade of Sino-Japanese relations. Both sides attach great importance to such documents, which are meant to characterize the state of their relationship at any given time and to serve as a guide for the future, pointing out areas of cooperation and attempting to solve – or at least neutralize – contentious issues. However, Tokyo and Beijing are not yet in agreement on the content of the proposed declaration.

For Japan, two questions loom large. First, Xi’s visit is an unmissable occasion to move toward a solution to the Senkaku/Diaoyu issue, or at least to put a floor under the dispute. It would be very challenging for the government to try to sell to domestic audiences on a “fifth political document” that does not take any step in that direction. Yet the Chinese side has shown little flexibility or willingness to compromise.

Secondly, Japan wants to make sure the new document does not present a setback compared to the previous one negotiated during Abe’s first term as prime minister (and by his successor Fukuda Yasuo) and then-President Hu Jintao more than a decade ago. At the time, the two sides agreed to forge a “strategic relationship of mutual benefit,” a formula that underlined the two sides’ equality and mutual acknowledgment of each’s great power status. Now that the size of China’s economy has eclipsed that of Japan and with Beijing seeking to firmly establish its position as the center of Asian life, Tokyo is keen to preserve the gains of 2008. This means finding a formulation that reaffirms the equal status of the two sides and emphasizes the important role they need to play on the world stage. Abe’s government apparently favors a “global partnership” modeled on the one Japan had concluded with the United States back in 1992, but it remains to be seen whether this would satisfy China.

For Japan, the key is to reach an agreement that affirms the equal status of the two countries even as China’s rise continues

Beijing’s priority indeed seems to be first and foremost to use the state visit to Japan to further enhance Xi’s prestige and position as supreme political leader of the People’s Republic. It is for that purpose that agreeing on a “fifth political document” is considered crucial to begin with. If Jiang Zemin produced one such document in 1998 and Hu Jintao in 2008, it would be unthinkable for Xi, who delights in being called the most powerful Chinese leader at least since Deng Xiaoping, to not unveil his own. For the same reason, the Chinese side is keen to include in the fifth document mentions of Xi’s favorite terms like the “new era” he says China is now in, and the “Belt and Road” – an initiative that Japan has not rejected outright but remains ambivalent about.

China would probably prefer to have Japan accept a document that fits neatly into the network of partnerships that it has been steadily building over the last two decades, and contains some of the typical terms and topics associated with them. One key issue here is the “One China principle” – a reference to the status of Taiwan – that Japan has acknowledged in previous documents and in practice by not maintaining any official ties with the island, but never explicitly endorsed. One can doubt that Tokyo would be willing to go beyond a reiteration of its previously stated position.

Despite those various points of contention, it is highly likely that the two countries will eventually agree on a document and unveil it in time for Xi’s visit. After all, both sides are keen to show that their deepening diplomatic dialogue can produce concrete results and know that cooperation on issues of common concern could be very beneficial regardless of bilateral security tensions. Still, it will be interesting to see what language will end up in the “fifth political document.”

Andrea A. Fischetti is a government scholar conducting research on Asia-Pacific Affairs and East Asian Security at the University of Tokyo and at the Asia Pacific Initiative. He was a visiting student at the Hiroshima Peace Institute of Hiroshima City University, and a research assistant at the House of Commons in the British Parliament. Mr. Fischetti earned his MA in War Studies from King’s College London, following a BA with First Class Honours in International Relations, Peace and Conflict Studies.

Antoine Roth is assistant professor at the Faculty of Law of Tohoku University, working on Sino-Japanese relations, China's foreign relations, and East Asian international affairs. He holds a PhD in International Politics from the University of Tokyo and a MA in Asian Studies from the George Washington University and a BA in International Relations from the University of Geneva. He has previously worked at the Swiss Embassy in Tokyo and has been a visiting student at Fudan University in Shanghai.