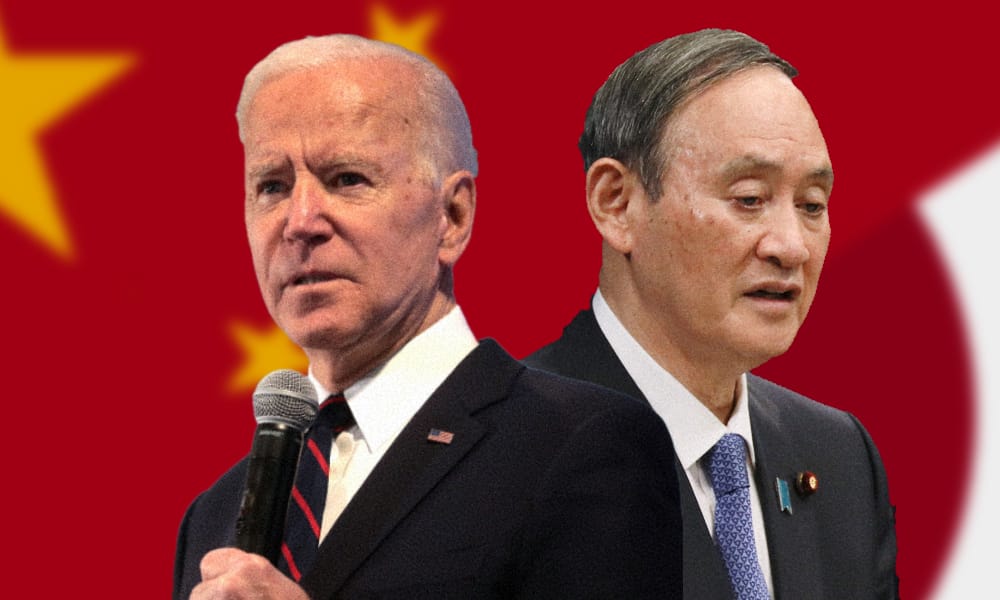

Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide will meet with U.S. President Joe Biden in Washington, DC on April 16, the first meeting between these heads of state – each of whom succeeds a predecessor who left a mark in their own way. One of the most important differences between the Biden administration and the Trump administration is on China, with Biden’s administration desiring a multifaceted relationship – cooperating in some spaces and confronting on others – rather than competition across all fronts. His administration needs to think carefully about how to achieve that: these issues aren’t always siloed, and Xi Jinping’s administration may not even be interested in cooperation. To that end, learning from Japan’s example might be the best option for the United States. The combination of cooperation and confrontation which has defined much of Japan’s relationship with China suggests that a useful goal for U.S. strategy, leveraging its geopolitical heft in ways Japan and other states cannot, is to create an environment based on coordinating on common interests and building a common purpose where countries are not forced to pick sides in a pseudo-Cold War.

Just because Japan doesn’t want to “choose” between the United States and China doesn’t mean its concerns about the security threat from China are not very real and very profound. Japan is indeed recalibrating its approach to China – merely without the usual sturm und drang that accompanies such shifts in the United States. Japan is a veteran in terms of China’s coercive diplomacy – it has already seen its citizens detained, violations of its airspace, territorial incursions, and economic coercion. Japan was well aware of supply chain issues related to its economic relations with China before the U.S. Department of Defense announced its own task force to address those issues earlier this year. Once notoriously reluctant to speak out against human rights abuses, there is a bipartisan caucus of lawmakers in the Japanese Diet focusing on human rights violations in China and the group has issued statements condemning China’s actions in Hong Kong and Xinjiang.

In other words, there shouldn’t be any doubt that Japan acutely feels a sense of threat from China – as Inoue Ichiro of Kwansei Gakuin University put it, “The more China rises, the more vigilant Japan becomes.” Too much analysis, however, has emphasized Japan’s constitutional constraints on its military, assuming that Japan is content to freeride off its alliance with the United States – but this can only explain so much of Japan’s response to its security environment. Japan’s most opportune moment to remove those constraints may have just passed: with Chinese territorial incursions becoming very real, public opinion increasingly identifying China as a threat, and in Abe Shinzō a prime minister who had unprecedented political capital to revise Japan’s constitution to become a more “normal” military state (and the stated ambition to do so), there should have never been a wider window for Japan’s remilitarization.

Instead, the facts that Japan’s military spending remained mostly flat in real terms and that constitutional revision was never achieved mean, firstly, that the ceiling for a prime minister’s power may be lower than was thought. The issue isn’t completely frozen – if anything drives Japanese decision makers to adapt its defense policies, it is China. Despite his failure to revise the constitution itself, Abe was still able to pass legislation reinterpreting the constitution to allow the SDF to participate in collective self-defense, a long-time ambition that got added impetus following China’s incursions around the Senkaku Islands. Further expansions of Japan’s defense capabilities within the existing constitutional bounds are worth taking seriously as well. While an SDF contribution to Taiwan’s defense probably isn’t imminent, it is worth remembering that the 1996 Taiwan Straits crisis provoked meaningful change to Japan’s defense guidelines.

Secondly, the challenge presented by China has driven Japan to double down on the rules-based order – building agreements and deepening partnerships with India, ASEAN, and Australia. With their varied threat perceptions, getting these partners aligned means selling them on the value of economic cooperation and democratic governance. The framework of the rules-based order is important and has buy-in among decision makers across regional capitals – but most importantly allows the United States and its partners to stand for something rather than simply being a China containment brigade and gives a positive ambition for China to attain as a global leader. The order needs to be attainable rather than an exclusive club. The challenge is how much heterogeneity is acceptable and where lines can be drawn – the violent Hindu nationalism in Modi’s India and Duterte’s bloody drug war in the Philippines deserve their place among threats to liberalism in the region, and this may also give the United States additional motivation to address its antidemocratic spasms at home.

China’s economic promise is still a powerful draw and cultural connections are deep and fundamental, and neither should be dismissed. The United States and most other Western economies can look back at the idea that economic engagement was a fanciful opportunity to mollify China’s authoritarian tendencies with the unstated assumption that economic relations are an option that can be calibrated, even down to zero if need be. Yet for most every economy in East Asia the idea that economic relations are somehow optional would be approaching insanity, and all recognize that Chinese raw materials are essential for economic growth and its consumers are an essential market. According to JETRO’s 2020 polling of Japanese firms, only 7.1 percent said that they would downsize or withdraw their operations from China.

Demanding that Japan (and other regional partners) accept Washington’s framing of China, as the Trump administration seemed to do, risked alienating to U.S. partners in East Asia – they depend on China economically, don’t want to alienate China completely, and all have different problems and goals with China and the United States. Every country in the region has its own equities and interests, especially in their relationship with China and accepting – and living with – disagreements among regional partners is essential. As Ryan Haas of the Brookings Institution points out, this will even build political space for the United States as countries “will feel more comfortable working with the United States on issues relating to China when doing so is not perceived as an expression of hostility towards China.”

The most valuable lesson the United States could take from Japan is to accept China’s rise as inevitable. Norms of human rights and rules must be insisted upon and military incursions can be deterred, but if China, with a population three times that of the United States, wants to achieve a similar level of per capita wealth, that means China’s economy would eventually become three times larger than that of the United States. This does not mean accommodation or acceptance of a G2 arrangement (which may even represent the nightmare scenario for Japan and other states) but confront and cooperate as necessary and avoid essentialist talk. The United States could learn from Japan’s experience.

Paul Nadeau is an adjunct assistant professor at Temple University's Japan campus, a visiting research fellow at the Institute of Geoeconomics, and an adjunct fellow with the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He was previously a private secretary with the Japanese Diet and as a member of the foreign affairs and trade staff of Senator Olympia Snowe. He holds a B.A. from the George Washington University, an M.A. in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University, and a PhD from the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Public Policy. He should be general manager of the Montreal Canadiens.