The Special Strategic and Global Partnership between Tokyo and New Delhi has established itself as a noteworthy example of a successful and mutually beneficial bilateral. As 2022 marks the 70th year of India-Japan diplomatic ties, the new joint statement, titled “Partnership for a Peaceful, Stable and Prosperous Post-COVID World,” signals important narratives for the hallmark anniversary. Yet certain cracks in the ties are beginning to show: Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s recent state visit to India – marking the first by a sitting Japanese prime minister since the onset of the pandemic in 2020 – signaled a deeper resolve by Tokyo to address emergent issues threatening opinions potentially divided. Yet questions remain as to the possible challenges that the India-Japan bilateral face and whether Kishida can maneuver the same to maintain positive and holistic growth that allows the Tokyo-Delhi bilateral to reach its true potential of its “global” partnership.

Conflicting national interest in the way?

Japan and India are traditional partners, driven by factors such as a strong personal camaraderie between national leaders, common regional challenges vis-à-vis an assertive China, and the goal to ensure continued presence of the United States in the region. Annual state-visits of national leaders between Japan and India being common practice for years, so the visit by Kishida is not uncharacteristic. However, the timing of the trip is critical, highlighting Tokyo’s uneasiness with Delhi’s foreign policy maneuvering, arriving in India as a “Samaritan of the Eleventh Hour” to address what U.S. President Joe Biden has called India’s “shaky” response by Delhi to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Indeed, India’s “strategic silence” on Ukraine was a key topic on the agenda, especially as India – and China – remain two notable international powers that have not condemned Moscow.

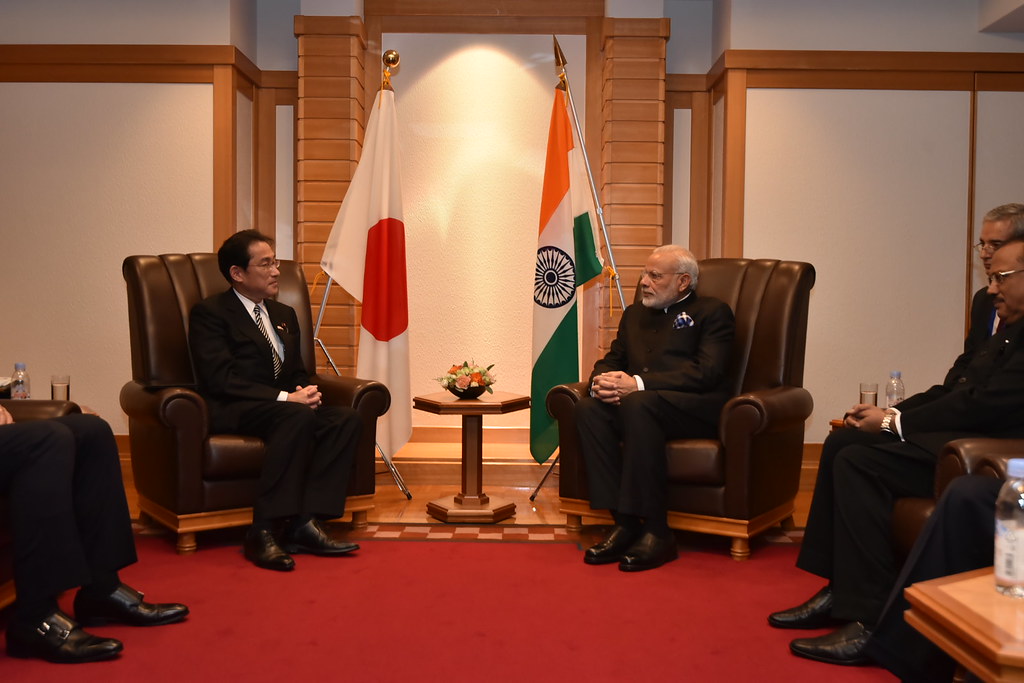

While Tokyo has adopted a hard line on the invasion of Ukraine and has sought to stand along its Western allies and seek to lead a strong Asian anti-Putin response to the crisis, New Delhi has abstained in all United Nations forums on sanctions pertaining to Russia. Herein, Kishida’s state visit aimed to urge India to take a similar tough stand against Delhi’s traditional defense partner Russia, yet his efforts fell short of convincing India’s Narendra Modi to move away from his non-aligned Russia-Ukraine approach. The joint statement that followed the meeting referenced Ukraine only by reiterating India’s diplomatic stand for an “immediate cessation of violence” and promotion of “dialogue and diplomacy” without condemning Moscow. Hence, while Delhi would have preferred a more nuanced understanding of its limitations by its partners, it has managed to maintain neutrality.

But the problem is bigger and more nuanced than a disagreement on responding to Russia’s invasion. India’s position on Ukraine should more clearly reveal how it can balance its national interests against international expectations. India’s ties with Russia as a traditional defense partner are no secret, and Delhi has for long maintained a careful balance between the United States and Russia. Meanwhile Russia-Japan ties have had strains stemming from territorial disputes; even as attempts at deepening engagement have been made since the time of former prime minister Shinzo Abe, there remains nominal dependence by either side on the other. This allows Japan, unlike India, to condemn Russian actions with much more confidence while staying true to its national interest. Differences on Ukraine are a key reminder to both countries that even in their successful bilateral, there remain areas of difference largely stemming from varying national interests.

India’s position, then, would not exactly be a surprise to a seasoned foreign policy specialist like Kishida whose hope was to build on his expertise as Japan’s longest serving foreign minister –who last visited India in 2015 in a successful trip that furthered the “Special Partnership for the Era of the Indo-Pacific.” However, what emerges as a challenge for Tokyo is that this marks the second time in three years that India has strongly refused Japan on a major topic, reflecting the increasingly nationalist and strengthened place Delhi is commanding for itself in Asia. India’s refusal in 2019 to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) marked a major setback for Japan, which fears the venture will become China-dominated in the absence of Delhi. Citing that “there will be no compromise on core interests,” Delhi has maintained its aversion to the partnership, refusing to review its decision despite multiple attempts by Tokyo to convince it otherwise.

Arguably, Japan has also picked its national interest over Delhi in the bilateral relationship. India, South Korea, and Australia’s invitation to the 2021 meeting of the Group of 7 (G7) industrialized democracies –in which Japan remains the only Asian member –received pushback from Tokyo, stemming from Japan’s concerns over how the move would look anti-China, prevailing domestic turmoil under Suga, and a fear that it would diminish Tokyo’s own power projection as the only Asian voice in the grouping. While South Korea and Japan have historic animosity, the reluctance on Tokyo’s part to have Delhi and Canberra – both Quad and trilateral partners – as possible additions to the G7 was surprising, especially within Indian strategic circles. Japan has always promoted economic multilateralism, and is a member of the Group of Four (G4) with India. Hence, both India and Japan have deferred to national interests, signaling the need for regrouping between the two invaluable partners to rebuild trust.

Looking at the future: Kishida right man for the job?

Standing tall in —or outside of— Abe’s shadow has proved to be a daunting task for each of his successors. Suga Yoshihide’s brief one year stint at the job threatened the return of “revolving door” leadership style in Japan. Meanwhile, Kishida’s approval ratings have remained relatively high, despite some low periods, drawing mostly from his government’s perceived success in handling COVID-19 outbreaks. Regardless, Suga’s and Kishida’s insistence on largely continuing Abe’s foreign policy direction has resulted in stability regarding Tokyo’s global posturing. But on Russia, Kishida has dropped Abe’s conciliatory approach with a strong response that serves as a landmark moment for Japanese foreign policy.

Meanwhile, ties with India have largely maintained their upward trajectory with the signing of agreements ranging from better mobility for skilled workers to deeper cooperation in the information and communications technology (ICT) sector. Nonetheless, the bilateral relationship has missed the personal camaraderie that was a hallmark of Abe’s diplomacy with Prime Minister Modi. The absence of such a connection is evident as differences on national interests come into sharper relief in post-Abe times — while under Abe, Japan had gone so far as to state that it would not join RCEP without India, but the current differences on the G7 and Russia reveal a significant shift.

Rejuvenating these bilateral meetings will be critical to the partnership moving forward. As the pandemic subsides, state-visits and in-person direct engagements between top leadership must be revitalized, especially among top leadership. As the target of ¥3.5 trillion in public and private investments in India has been achieved, the signing of the new ¥5 trillion yen (USD 42 billion) investment in India over the next five years is a welcome move by Kishida, particularly with a continued focus on the Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (EPQI) in Northeast India. Potential growth of the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI) along with strengthening cooperation in the field of science, technology, trade and third country would also be ideal areas for the bilateral to focus on in the coming months. Finally, while the visit saw a fruitful discussion on China, future talks should try to provide a much needed push for both countries to reinvigorate their initiatives like the Platform for Asia-Africa Business Cooperation, especially amidst a growing Chinese footprint in Africa.

Japan-India ties have for long served as a hallmark of positive diplomacy, and their growth is critical to both parties. Kishida’s skills as an erstwhile foreign minister can prove to be the catalyst that drives home Japan’s diplomatic outreach and domestic political balancing, with the Tokyo-Delhi bilateral emerging as a deserving victor.

Eerishika Pankaj is the director of the Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA), a New Delhi based think-tank which focuses on decoding domestic Chinese politics and its impact on Beijing's foreign policymaking. She is also an editorial and research assistant to the series editor for Routledge Series on Think Asia; a young leader in the 2020 cohort of the Pacific Forum’s Young Leaders Program; a commissioning editor with E-International Relations for their Political Economy section; a member of the Indo-Pacific Circle and a council member of the WICCI’s India-EU Business Council.