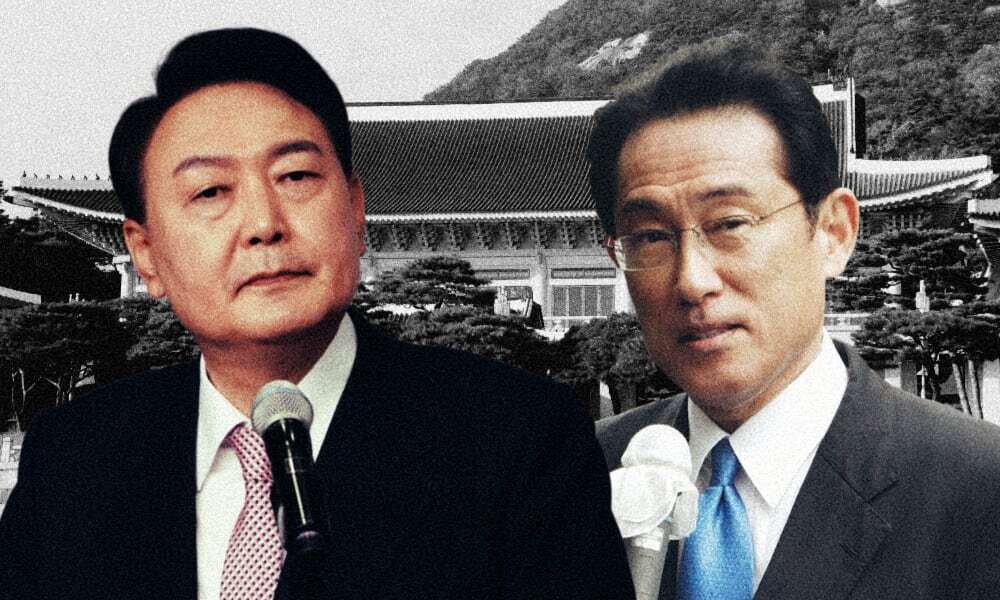

Conservatives in Japan and South Korea heaved a sigh in March upon the news of Yoon Suk-yeol’s election as South Korea’s next president, hoping that a conservative victory would restore Japan-South Korean relations from what has been their lowest point since normalization in 1965. The incoming Yoon administration seems committed to improving bilateral ties, as demonstrated by his sending of a policy consultation delegation to Tokyo for a five-day visit ahead of his inauguration, but history-related diplomatic spats will continue to flare up despite promises on both sides to make efforts because Japan and South Korea see the issue in a fundamentally different way – for Japan, it is a legal issue, with the 1965 agreement settling all disputes, while for South Korea, the issue is normative and cuts to their sense of self-identity.

The incoming Yoon administration seems committed to improving the situation. Relations between the two U.S. allies hit rock bottom in 2019 and 2020 because of a confluence of factors, beginning with the South Korean Supreme Court rulings in 2018 ordering Japanese companies to compensate forced laborers during colonization, followed by Japan’s removal of South Korea in 2019 from its list of favored trade partners. The situation deteriorated from there, as South Korea threatened to resume the process of terminating the intelligence pact it has with Tokyo, followed by both governments suspending the visa-waiver program for visitors from the other country, ostensibly a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but arguably more of a tit-for-tat move that turned a government-level squabble into an issue affecting people-to-people exchanges between the two countries.

Yoon had blamed Moon Jae-in and his administration for using historical issues for domestic politics, at the expense of ties with Tokyo. Yoon has instead promised a more pragmatic approach that decenters history and emphasizes the importance of Japan-South Korea relations in addressing more practical issues, such as security threats from North Korea. Yoon had presented a “grand bargain” deal with Japan as a solution to South Korea-Japan diplomatic conundrum during his campaign. What this deal looks like is uncertain, but the 1998 Kim-Obuchi joint declaration, which he mentioned he would reaffirm on the campaign trail, could be the model he has in mind. This declaration is considered a landmark agreement between Japan and South Korea that comprehensively opened a new chapter of relations. During the visit of Yoon’s delegation to Japan in April, his representatives delivered a handwritten letter from Yoon to Fumio Kishida; the latter also recognizing the need to improve bilateral relations as soon as possible.

For Japan, its dispute with South Korea is a legal issue, while for South Korea, the dispute cuts to their sense of self-identity

Yoon could be overrating his chances – simply changing the diplomatic tenor will not be enough to significantly improve Japan-South Korea relations because the problems are more fundamental than simply a question of tenor. The issue with Yoon’s approach is that he has misdiagnosed the outgoing Moon administration as the problem in Japan-South Korea relations. Moon’s administration had already proposed in late 2020 a declaration between Moon Jae-in and Suga Yoshihide modeled after the Kim-Obuchi declaration, but was rejected by Tokyo, citing the forced labor compensation ruling. If Yoon seeks a breakthrough with Japan, his administration would have to stop the seizing of Mitsubishi Heavy assets, but the domestic repercussions of this move within South Korea would be considerable. Yoon would be heavily criticized not only by the victims of forced labor and surviving “comfort women,” but by South Korean liberals who continue to hold a majority of seats in the National Assembly. As a political novice who has already wasted considerable political capital over a plan to relocate the presidential executive office and residence, any attempted solution that bypasses the victims is likely to cost Yoon significantly – indeed, the failure to adequately consult the victims themselves was one of the key reasons for the Moon government questioning the validity of the 2015 comfort women agreement with Japan and dissolving the fund for survivors established by that agreement.

History issues have worsened over the past few years for two major reasons: the role of the 1965 normalization treaty and the increasing politicization of the relationship in both Japan and South Korea. At the core of the perennial bilateral disputes over history is the 1965 normalization treaty between South Korea and Japan. Under this agreement, Japan extended USD 500 million in grants and loans that included wages of requisitioned Koreans and compensation for damages. The divergence in the legal interpretation of this treaty has widened notably since the 1990s, when South Korea consolidated its transition from the authoritarian regime that negotiated the treaty and after more revelations about Japan’s colonial occupation were made public, particularly the first public testimony by a former South Korean “comfort woman.” For Japan, all bilateral issues pertaining to colonial rule have been, and would retroactively be, settled by the treaty, including any new testimonies such as those from Korean “comfort women.” Consequently, from Japan’s perspective, South Korea is to blame for exploiting historical issues for domestic political purposes and undermining international agreements between two sovereign states. As former foreign minister Kono Taro wrote, at the heart of the historical disputes is a matter of bilateral trust, and Seoul is the irresponsible signatory.

For South Korea, the 1965 treaty is more complex. South Korean leaders, both left and right, have also politicized the relationship with Japan and especially the court rulings, reflecting South Korea’s insistence that the dispute is a question of transitional justice centering victims, while reframing and politicizing the issue as an unfinished business. The South Korean Supreme Court in the early 1990s had ruled that the South Korean state had already received reparations from Japan through the 1965 agreement, meaning that any individual seeking reparations beyond what was covered in the treaty would need to sue the Japanese government directly. During the Roh Moo-hyun administration (2003-2007), the government took the matter into its own hands by interpreting the 1965 agreement as having excluded three specific issues related to colonial rule: the “comfort women” issue, the displacement of Koreans to Sakhalin Island, and atomic bomb victims. In the following years, the South Korean Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional for the South Korean government to not seek remedy or provide recourse for the victims. However, Seoul’s hands were tied as bilateral ties took a turn for the worse during Lee Myung-bak’s term (2008-2012). Seoul’s emphasis on human rights and democracy became at odds with the 1965 treaty and its intergovernmental focus.

History issues between the two countries have worsened as both countries have politicized the relationship

Just as they accused South Korea of reneging on their agreement, key decision makers in the Abe administration took a tougher stance against South Korea, reflecting a frustration among much of the Japanese public but particularly giving voice to conservative nationalists who saw the Moon administration as fundamentally untrustworthy. More broadly, the Japanese public, especially the younger generation, was generally supportive of Tokyo’s tough stance toward South Korea in 2019 after the Moon administration effectively annulled the agreement with the dissolution of the survivors’ fund. Yet public opinion polling in 2020 showed cautious optimism in Japanese perceptions towards South Korea, putting the onus on decision makers in both Japan and South Korea to frame the bilateral relationship in ways that avoid essentializing the other’s perspective.

Diplomatically, Kishida is known to follow the foreign policy tradition that prioritizes relations with countries in the Asia-Pacific region, but his foreign policy stance vis-à-vis South Korea is questionable. As the foreign minister who negotiated the now-dissolved 2015 comfort women agreement, Kishida has also generally hewed to the idea that South Korea is primarily responsible for the breakdown in ties. Equally doubtful is the support within the LDP towards Kishida’s view towards relations with South Korea. For instance, Masahisa Sato, head of the LDP’s Foreign Affairs Division, disagreed with Kishida meeting with Yoon’s delegation, given that Japan’s apparent dispute with South Korea is ongoing. An impending upper house election in July 2022 could make the Kishida administration reluctant to concede too much until after the election.

Put differently, the issue between Japan and South Korea is deeper than just a question of finding the right approach. The structural nature of the historical disputes between Japan and South Korea is rooted in the tension between Japan’s focus on state-centered international law and South Korea’s emphasis on transitional justice. Each country’s attempt to fit the dispute within their preferred framework has meant antagonizing the other in the international sphere and domestically giving space to those who seek to essentialize the relationship and see the worst in the other’s maneuvers. For a foreign policy novice like Yoon, this problem is too formidable to be resolved within his term.

Minseon Ku is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the Ohio State University. Her dissertation explores the effects of summitry on public perception of security