Welcome to instalment XLI (June 2022) of Sino-Japanese Review, a monthly column on major developments in relations between China and Japan that provides a running commentary on the evolution of this important relationship and helps to put current events in perspective.

When Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party pledged, in its manifesto for the October 2021 election, to raise Japan’s defense spending toward 2% of GDP, many doubted that this goal would be reached any time soon. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has changed that. The party has recommitted to the target, and this time opinion polls suggest a majority of the public is ready to support higher defense spending. The same goes for the acquisition of “counterattack capabilities”, another long talked-about proposal that has recently gathered momentum. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has been conducting a very active diplomacy, culminating in a summit with the US and the other members of the Quad at which concerns about China figured prominently. Unsurprisingly, Beijing sees such developments with alarm – and has been increasingly vocal about its concerns.

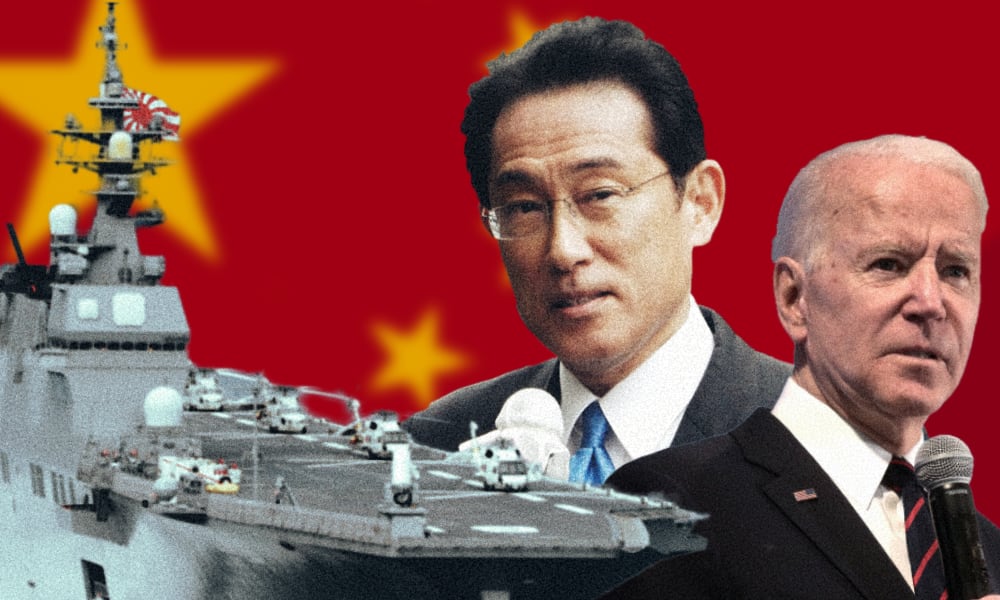

Japan’s annual Diplomatic Bluebook, published in late April, had a lot to say about relations with China. It sought to present a balanced picture, highlighting areas of cooperation and stressing the need to maintain a “healthy and stable relationship” even as it expressed deep concerns about China’s activities around the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, its broader attempts to “unilaterally change the status quo by force” in its nearby seas, and the growing pressure it is putting on Taiwan. Those expressions of concern have taken on additional urgency in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which explains the renewed push to significantly increase Japan’s defense budget. Although the pace of increase and its modalities are set to be a topic of intense political and bureaucratic debate, the slow defense build-up of recent years is undoubtedly set to accelerate. Kishida ensured as much when he made a public commitment in that sense to visiting U.S. President Joe Biden.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has given fresh urgency to Japan’s concerns about China’s activities in neighbouring seas

Biden’s visit and the ensuing Quad summit came at the end of a period of intense diplomatic activities that saw Kishida tour several Southeast Asian and European countries before welcoming the top two European Union officials in Tokyo. Ukraine of course figured prominently on the agenda of all those meetings, but so did China. In his tours of both regions and in his meeting with EU leaders, Kishida promoted defense cooperation and sought to emphasize joint opposition to attempts to change the status quo by force in Asian waters. The Quad summit endorsed similar language. The joint statement adopted by Kishida and Biden was more direct in its criticism of China and evoked the need to “strengthen deterrence to maintain peace and stability” in the Indo-Pacific.

Needless to say, this flurry of meetings didn’t go unnoticed in Beijing. A Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson denounced both Kishida’s tours of Southeast Asia and Europe and the Japan-EU summit for undermining peace and stability. The harshest worlds were reserved for the Japan-U.S. and Quad summits, which were accused of “building small cliques” and stoking confrontation. Additionally, Tokyo’s diplomatic activism and plans for a defense build-up were the target of a major commentary in the People’s Daily, which accused Japan of “letting wolves into the house” and escalating tensions to justify expanding its military capabilities. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi also directly warned his Japanese counterpart that “negative moves” regarding Taiwan and joint action with the U.S. were creating a “foul atmosphere” in the bilateral relations. The Chinese reaction was not limited to words either, as Beijing and Moscow staged a joint military exercise over the East China Sea to coincide with Biden’s visit to Tokyo, sending a clear signal that they would counter the U.S. and Japan’s activism with enhanced cooperation of their own.

A Chinese/Russian joint military exercise sent a clear signal that they would counter U.S.-Japan activism with enhanced cooperation of their own

A more elaborate picture of China’s understanding of recent developments in Japanese foreign and security policy can be gleaned from newspapers and academic analyses published in China. Along with the usual diagnosis that Tokyo is a willing “pawn” and “vassal” in Washington’s grand designs to contain China, commentators point out what they see as Japan’s deep sense of vulnerability that leads it to “meddle” in the Taiwan issue, its growing ideological alignment with the West, and the success of conservative forces in using the Ukraine crisis to shift public debate to the right and reconcile Japanese citizens with the idea of a more “normal” military unconstrained by the country’s traditional pacifism.

What is striking about this diagnosis is how closely it mirrors Japan’s own perception of China. Each considers the other in league with a disruptive great power (Russia in Japanese eyes, the U.S. in Chinese ones); each accuses the other of abandoning pragmatism for the pursuit of ideological purity; each sees the other increasingly driven by militant nationalism; each condemns the other for fueling tensions in the Taiwan strait. One retired Chinese navy officer even recently argued that Japan was taking incremental steps to strengthen its actual control of the Senkaku/Diaoyu, echoing Japan’s own account of the growing challenge from China’s navy and coastguard.

These mirroring narratives recall an earlier episode where China and Japan accused each other of undermining regional stability and international order following Japan’s nationalization of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in 2012. Although the Ukraine crisis, and the geopolitical shockwaves it has unleashed, is an external shock to Sino-Japanese relations rather than an internal one, it seems to have caused yet another escalation in mutual mistrust and threat perception.

Andrea A. Fischetti is a government scholar conducting research on Asia-Pacific Affairs and East Asian Security at the University of Tokyo and at the Asia Pacific Initiative. He was a visiting student at the Hiroshima Peace Institute of Hiroshima City University, and a research assistant at the House of Commons in the British Parliament. Mr. Fischetti earned his MA in War Studies from King’s College London, following a BA with First Class Honours in International Relations, Peace and Conflict Studies.

Antoine Roth is assistant professor at the Faculty of Law of Tohoku University, working on Sino-Japanese relations, China's foreign relations, and East Asian international affairs. He holds a PhD in International Politics from the University of Tokyo and a MA in Asian Studies from the George Washington University and a BA in International Relations from the University of Geneva. He has previously worked at the Swiss Embassy in Tokyo and has been a visiting student at Fudan University in Shanghai.