Welcome to installment XLII (July 2022) of Sino-Japanese Review, a monthly column on major developments in relations between China and Japan that provides a running commentary on the evolution of this important relationship and helps to put current events in perspective.

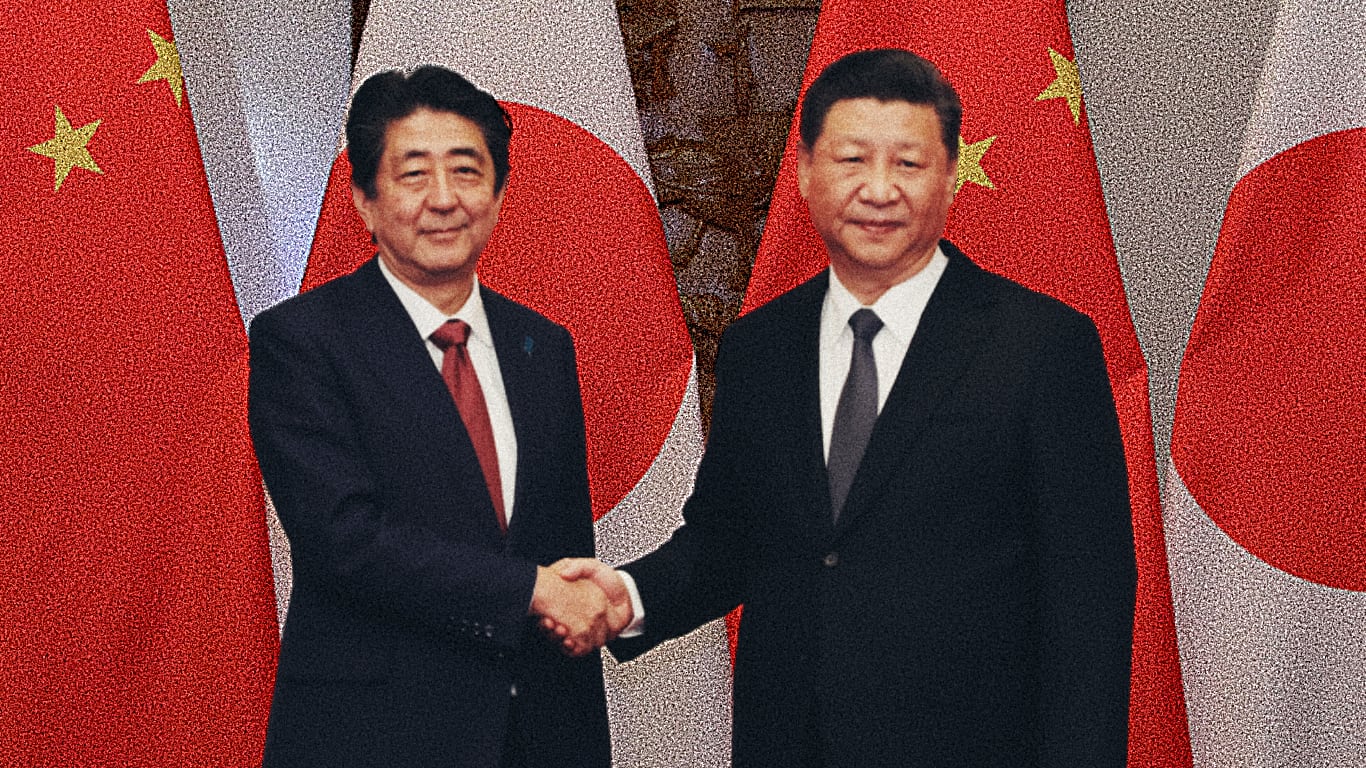

When Abe Shinzo, tragically assassinated on the campaign trail on July 8, took office as prime minister for the second time in December 2012, Sino-Japanese relations were at their lowest point since diplomatic normalization in 1972. In reaction to the nationalization of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, China had cut all bridges and was regularly sending maritime vessels to challenge Japan in the waters surrounding the islands. By the time Abe abruptly left office in September 2020 due to health issues, China’s pressure around the Senkaku/Diaoyu had continued to intensify, but normal diplomatic relations had been reestablished and only the covid-19 pandemic had prevented Xi Jinping from crossing the East China Sea for a planned state visit to Japan. This is despite the fact that, in the intervening years, Abe had relaxed the restrictions on the activities of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, increased defense spending, strengthened Japan’s alliance with the United States and security ties with Australia, India and Southeast Asian states, and repeatedly and vocally warned the international community about the challenge posed by an assertive rising China. His China policy therefore cannot be considered anything else than a success.

How was Abe able to manage the feat of stabilizing relations while also working diligently to build an international coalition able to push back against China’s excesses? The answer starts with his consistent focus and political acumen. Kevin Rudd is right to call responding to the rise of China the “organizing principle” of Abe’s prime ministership. This is what he pledged to do when campaigning for the top job, and he oriented his whole foreign policy toward that objective, which also partly informed his unsuccessful attempts to build a partnership with Russia and to draw a line under the “comfort women” issue with South Korea. Yet he could not have conducted such a proactive foreign and security policy without political stability at home. His success in strengthening the authority of the office of the prime minister and durably establishing a dominant position within the notoriously regicidal Liberal Democratic Party allowed him to negotiate with Beijing from a position of strength. Chinese leaders recognized this, and understood they had no choice but to deal with Abe.

Another important reason for Abe’s success was his pragmatism. He was an unabashedly nationalist figure with a strong inclination to downplay Japan’s imperial era atrocities. He visited the controversial Yasukuni Shrine one year into his tenure, attracting much criticism from China and elsewhere. Yet he knew enough to subordinate his passions in pursuit of the bigger picture. This can be seen for instance in the moderate tone of his speech on the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II in August 2015.

Despite his unabashed nationalism, he knew enough to subordinate his passions in pursuit of the bigger picture

In relations with China, the Abe administration clearly stated its position that attempts to change the status quo by force in the East China Sea were unacceptable, but that Sino-Japanese relations were too important for both countries and for international peace and stability writ large to let issues in dispute disrupt normal inter-governmental interactions. Abe’s team worked hard to repair the relationship, leading to a “four points unterstanding” on the need to improve ties and to a first – brief and not exactly friendly – meeting between Abe and Xi in late 2014, opening the way for a progressive resumption of diplomatic dialogue. In the following years, hawkish voices critical of China’s pressure tactics around the Senkaku/Diaoyu and human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong came to fully dominate Japan’s ruling circles, but Abe stayed the course, based on his assessment of the need to continue engaging China even as he sought to compete with it geopolitically.

In this geopolitical competition, Abe also successfully leveraged Japan’s diplomacy to help align regional interests in favor of a rules-based order. Already during his first term in office in 2006-2007, he had sensed that a diplomatic network on Asia’s rim could prove an effective counterweight to a rising China. He advanced the idea of a “confluence” of the Indian and Pacific Ocean and of a “democratic security diamond” with the United States, Australia and India – precursors of the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” and “Quad” respectively. With this, he laid the groundwork for what has now become the main alternative to China’s vision for a Sinocentric international order in Eurasia.

His instincts also allowed him to push Sino-Japanese relations in a positive direction at two key moments. First, the aforementioned “four points understanding” was only made possible by the acknowledgment, both on the Chinese and Japanese sides, that they would have to “agree to disagree” to move forward. Abe did not abandon Japan’s official rejection of the very notion that there is a territorial dispute around the Senkaku/Diaoyu, but accepted that China would release its own version of the document, speaking of different “positions” (zhuzhang) rather than “views” (kenkai) and suggesting that Japan had acknowledged China’s claim to the islands. The other turning point was Abe’s declaration of support for Xi’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative in May 2017, which allowed high level exchanges to significantly gather pace. In both cases, Abe understood that small, symbolic gestures of respect for China’s position and status could go a long way in improving bilateral ties even in the absence of more concrete concessions. More broadly, he knew that “normal” diplomatic relations needed to be actively maintained through engagement at the top in order to prevent security tensions from spilling over.

Despite Abe’s achievements in improving Sino-Japanese relations, he left much undone

Abe consequently left Sino-Japanese relations in a much better place than he found them. Yet his achievements should not be overestimated either. Japan still does not have an effective way to counter the constant ratcheting up of Chinese pressure surrounding the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. It has not solved the dilemma between growing economic dependence on China and growing geopolitical tensions either. Nor has it reconciled its desire to maintain both a very close alignment with the United States and stable relations with China at a time of worsening tensions between the two superpowers. And then there is Taiwan. After he left office, Abe became much more vocal in his support for the island’s continued autonomy and for greater Japanese involvement in the maintenance of cross-strait stability along with the United States. Yet although he emphasized the duty of politicians to lead and shape public opinion, he did little to sensitize the Japanese public to the fact that assuming a greater role in the Taiwan issue would mean a greater risk of being involved in a devastating conflict with China.

At the root of all these issues may lie a dearth of strategic thinking. Abe had a clear sense of the direction he wanted to take Sino-Japanese relations but was unable to foster a healthy debate in Japan about the choices facing the country, its ultimate objectives, and the means necessary to achieve them. This task will fall on Abe’s successors, and only time will tell if they will be able to build on what he achieved. The fact that Abe’s leadership and character have left a profound mark on Sino-Japanese relations will in any case remain certain.

Antoine Roth is assistant professor at the Faculty of Law of Tohoku University, working on Sino-Japanese relations, China's foreign relations, and East Asian international affairs. He holds a PhD in International Politics from the University of Tokyo and a MA in Asian Studies from the George Washington University and a BA in International Relations from the University of Geneva. He has previously worked at the Swiss Embassy in Tokyo and has been a visiting student at Fudan University in Shanghai.

Andrea A. Fischetti is a government scholar conducting research on Asia-Pacific Affairs and East Asian Security at the University of Tokyo and at the Asia Pacific Initiative. He was a visiting student at the Hiroshima Peace Institute of Hiroshima City University, and a research assistant at the House of Commons in the British Parliament. Mr. Fischetti earned his MA in War Studies from King’s College London, following a BA with First Class Honours in International Relations, Peace and Conflict Studies.