The assassination of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō was a shocking event that rocked Japan and reverberated across the globe. There is no doubt about the impact or influence that Japan’s longest serving prime minister had on the nation’s politics, but acknowledging what an important figure Abe was also opens the door to much speculation about what may follow now that he is gone. There is no modern precedent for something like this, making it difficult for anyone to assess the true effects of Abe’s assassination; absent that, it is necessary to focus first on the practical issues that have been created by his demise.

Abe’s death created three vacancies, formal or informal, that the ruling Liberal Democratic Party must fill. The first is in his own LDP faction – Abe was the head of his party’s largest bloc, the Seiwa Seisaku Kenkyūkai (or simply the Abe Faction, formerly the Hosoda Faction), a position that he took over in November last year. Inheriting the leadership of the faction allowed him to wield direct influence in picking the party president, setting the policy agenda, negotiating cabinet appointments, and election-related decision making.

With Abe now gone, who will take over this role is an open question. It is reasonable to assume that the faction will not name a new leader until after all funeral proceedings are complete, with the traditional 49 day mourning period and the arrangements for September’s state funeral giving the faction some time to make its choice. Once that is over, however, the faction will have little time to waste before formalizing its next leader. Abe had long been the central pillar of this faction, even under former faction leader Hosoda Hiroyuki, and had a loyal group of followers in its ranks, but none of the remaining faction members can match either the political prowess or the dynastic advantages of Abe or other LDP heavyweights. That will not, of course, stop many of them from vying for the top spot anyway.

Of the many who might aspire to the post, the one who will fight the hardest is former Education Minister Shimomura Hakubun. Shimomura is now the acting chairperson of the faction, and he had already tried to throw his hat into the ring for the prime minister’s office last October (before being convinced otherwise by resigning incumbent Suga Yoshihide). His interest in the faction leadership is almost certainly rooted in the understanding that being a faction head is essentially a prerequisite to becoming prime minister.

Shimomura will have competition though, as he is just one of seven individuals serving on a council which the faction established to exercise collective leadership in the immediate aftermath of Abe’s death. The others include former LDP General Affairs Chairperson Shionoya Ryū, former Minister of the Economy Seko Hiroshige, former Ministers for Revitalization Takagi Tsuyoshi and Nishimura Yasutoshi, current Chief Cabinet Secretary Matsuno Hirokazu, and current Minister of Economy Hagiuda Kōichi. Each comes with their own strengths and weaknesses; Seko, for example, was close to Abe and padded his portfolio with key cabinet postings from 2012 to 2020, but being an Upper House politician all but eliminates his chances of becoming prime minister. Matsuno, meanwhile, has been building his political stature as the Chief Cabinet Secretary, but lacks sway over the broader conservative base inside the LDP.

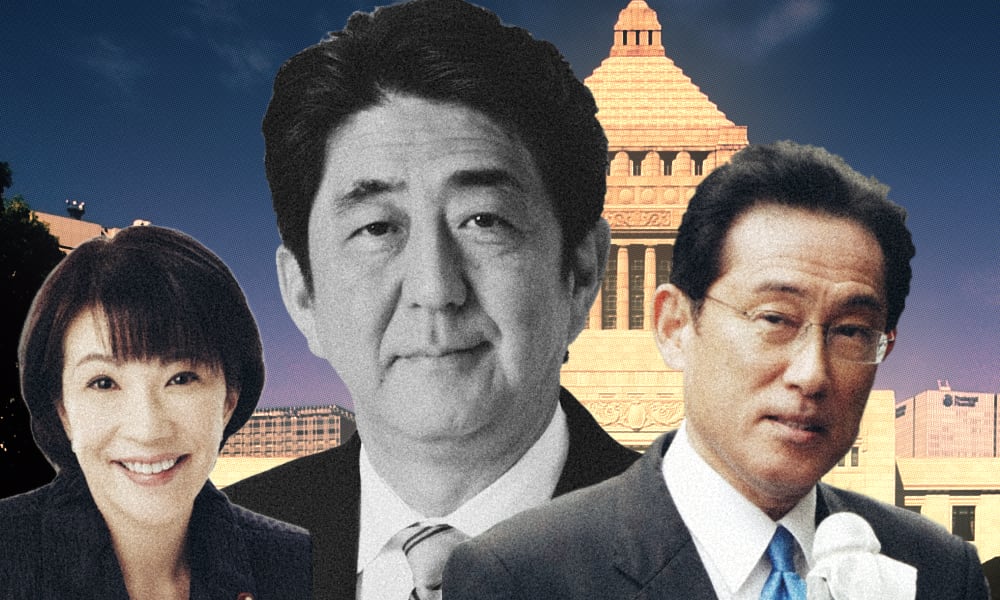

The Abe Faction is now ruled by an interim council of seven powerful lawmakers, many of whom may see themselves as future faction leaders

In other words, there is no obvious replacement for Abe within his faction – which means that things could get turbulent as its members fight for power. It is even possible that this conflict could split up the current Abe faction, following the path of the Koga faction, which broke apart into the Kishida faction and the Tanigaki group based on disagreements over its leadership back in the early 2010s. Inevitably, someone will inherit the Abe faction – or at least parts of it – but for now there is simply no way of predicting who will win and who might split off.

The second vacancy is tied to the first, but is an informal position – who will succeed Abe as the LPD’s top neoconservative? LDP factional membership is not separated along ideological lines, which means that not all members of the Abe faction are on the political right-wing, and not all conservative-leaning LDP members are in the Abe faction. Abe’s long-term success came in part because he was not strictly bound to factional politics and could leverage support from conservative voices across the party to his ends.

His logical successor in that role might be Takaichi Sanae, an unabashed neoconservative and close ally of Abe who currently serves as the chairperson of the party’s powerful Policy Research Council. Takaichi made a strong run for the Party presidency last year, and she has already expressed her intent to succeed Kishida Fumio as Japan’s next prime minister. But Takaichi, who is not a member of any faction, is likely to face stiff competition from ambitious contenders such as Shimomura within the Abe faction. Plenty of Abe protégés aspire to become prime minister one day, which will almost certainly create a showdown – albeit one that will likely play out behind the scenes rather than spilling out into the public realm.

Takaichi Sanae is one logical successor for Abe’s role as neoconservative leader – but many of his other protégés have similar aspirations

The final vacancy to be filled is Abe’s own seat in the Diet. Prior to his death, his home district in Yamaguchi Prefecture was already set to become a battleground in a clash with Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa. Due to redistricting, Hayashi’s Yamaguchi seat was slated to disappear in the Lower House election, forcing him to choose between challenging one of the LDP incumbents in the prefecture or running on the less influential proportional representation ticket. Before Abe’s death, Hayashi’s choices for a Yamaguchi single-member district were to run against Japan’s longest serving prime minister, the country’s current Defense Minister Kishi Nobuō, or the son of former LDP Vice President Komura Masahiko. None of these were encouraging options, but with Abe’s former seat now vacant, Hayashi and his allies can make a play for him to become the candidate in this constituency.

While the necessity of filling each of these vacant positions is clear, which establishes much of the agenda for the coming months, there’s much more that remains unknown. For one, it’s unclear how these crucial vacancies may affect Kishida’s approach to intraparty politics. Will he exploit the fact that the conservative bloc inside the LDP is weakened and seek to erode their internal power base, or will he exercise patience and allow them to regroup in a bid for unity within the party? It’s also unclear how this might influence Kishida’s policy priorities, such as those related to his so-called “New Capitalism” economic agenda. While it’s possible that Kishida will use the next few months until the extraordinary session of the Diet to clear the docket of LDP-prioritized legislation, the agenda that Kishida puts forward and the policies that get resourced in next year’s budget will afford observers a window into his priorities.

Finally, how will these vacancies affect the pecking order in the LDP? The safe assumption is that it will strengthen Kishida and his immediate supporters. However, that remains an assumption, and the moves that take place in the coming weeks and months will impact the power rankings of politicians inside the LDP.

The coming months will offer several important indicators of how Kishida and other party power-brokers are planning to act

Going forward, there are a few key indicators to keep an eye on in order to understand where this is going. One obvious indicator is the upcoming cabinet reshuffle. The Kishida cabinet is due for a reshuffle, and while some media outlets are reporting that it could be as early as August, the window extends anywhere between now and late December. Observers should expect wholesale change of the subcabinet positions (state ministers and parliamentary vice-ministers), as well as many of the cabinet spots and LDP executive posts. Who gets moved out and who stays will offer essential clues into Kishida’s political designs.

The timing of the cabinet reshuffle is also important for understanding Kishida’s future approach as prime minister. If he reshuffles promptly, he can exploit the weakened Abe faction, but if he gives the faction time to pick a new leader and find its footing in negotiations over cabinet positions, that would represent a concession and a bid to maintain party unity. Either way, the timing itself, along with the personnel choices, will offer insight into how Kishida is managing intraparty players and factions.

Finally, the LDP’s approach to resolving the by-election for Abe’s vacant seat in Yamaguchi will offer a deeper glimpse into the behind-the-scenes politicking within the party. There are election laws that could dictate the seat be filled by the end of October, but some extension to that schedule is also possible. No matter when the by-election comes, it will create an important debate inside the LDP as to who should be the candidate in that seat – and who might have to settle for running on the proportional ticket in the next Lower House election. The coming months will, therefore, be pivotal for Kishida and the LDP.

Michael MacArthur Bosack is the special advisor for government relations at the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies. He previously served in the Japanese government as a Mansfield Fellow.