On Wednesday, October 11, the Hamamatsu Branch of the Shizuoka Family Court ruled in favor of allowing 48-year-old Suzuki Gen to change his gender in Japan’s family registry. The man told the press he was pleasantly surprised and had trouble believing this ruling was made. Celebrated as a landmark decision, the court’s ruling was exceptional because it allowed Suzuki to change his legal gender without fulfilling one of the requirements demanded by the so-called “Act on Special Cases in Handling Gender Status for Persons with Gender Identity Disorder”. The reason the decision was so much cause for celebration is because the courts are the only option for Japan’s trans people to change what they describe as onerous burdens to identify as who they are – and without greater political engagement, any decisions in these areas by Japan’s courts are disproportionately consequential for those seeking change.

The GID law, which was passed by the Diet in June 2003 and came into force a year later, stipulates a number of requirements people need to satisfy if they want their request for a change of legal gender to be recognized. The law’s second article states that one needs to be diagnosed with ‘Gender Identity Disorder’ (GID) by two or more physicians deemed to possess adequate knowledge and expertise. If this is indeed the case, there are five more clauses that need to be satisfied:

- be older than 20 years old.

- be unmarried at present.

- be without children who are legal minors.

- be without functioning reproductive glands.

- have body parts that appear to resemble the genitalia associated with the gender you seek to register.

In recent years, the law’s harshness has been the subject of much international scrutiny, but at the time when it was drawn up and enacted, these clauses, apart from the one demanding childlessness, were not completely out of the ordinary compared to similar laws in other countries. Nevertheless, it was certainly controversial among those it was supposed to help. For some, it meant a big step forward — an opportunity to participate in society as their true selves without being held back by what had been recorded in the family register when they were born. But for many others, these strict requirements meant they either had to make big personal sacrifices, give up on legally transitioning, or continue to advocate for further legal changes.

The clause about childlessness particularly caused an uproar within Japan’s trans community. Even before the GID Law passed the Diet, an advocacy group was launched specifically to lobby for the removal of this clause from the planned bill given that the original form of the law banned parents from changing their legal gender regardless of their child(ren)’s age. It was only in 2008 that an amendment changed the requirement to what it looks like now.

For Suzuki Gen, it was the fourth requirement that created a big obstacle. Hormone therapy and top surgery had already relieved him of the discomfort he once felt towards his body, and he had been living as a man for a number of years. As much as Suzuki wanted to see this lived reality reflected in the family register, he did not want to undergo an unnecessary, financially and physically demanding surgery that would render him sterile. In October of 2021, less than three years since the Japanese Supreme Court had upheld the constitutionality of the sterilization clause of the GID Law in a different case, Suzuki decided to file for a change of legal gender at a family court. Not only did this court end up ruling in his favor, it also deemed the requirement to be unconstitutional, citing Article 13 of Japan’s constitution, which states:

“All of the people shall be respected as individuals. Their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness shall, to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare, be the supreme consideration in legislation and in other governmental affairs.”

The decision was a major win for Suzuki, and a spark of hope for many others who are frustrated by the harsh demands of this law.

But while the Shizuoka Family Court set an important precedent, a different ruling, expected to be delivered on October 25, has the potential to either diminish or expand it. In this case, justices of the Supreme Court are reviewing this same topic again in a case launched by a transgender woman. On top of challenging the constitutionality of the sterilization clause, the woman and her team also object to the GID Law’s requirement regarding petitioners’ genitals.

Even though four Supreme Court justices unanimously ruled in favor of the law in early 2019, there is a very real possibility for a different ruling this time. Two of the presiding supreme court justices in the 2019 case released a supplementary statement where they remarked that the law should perhaps be reviewed again as societal values change, and further that requiring surgery was potentially in violation of Article 13 of the Constitution. Unlike the 2019 case, the current case has been sent to the Supreme Court’s “Grand Bench”, consisting of all fifteen justices, so that the constitutionality can be properly examined.

January 2019 might seem fairly recent, but much has happened in Japan since then. Through activism and increased media attention, trans people and other members of the LGBTQ+ community have made significant gains in terms of visibility. In contrast to the national government’s general inability — or unwillingness — to implement LGBTQ+-friendly policies, local governments at both the municipal and prefectural level across the country are increasingly doing their best to spread awareness, improve situations, and solve issues for the LGBTQ+ community.

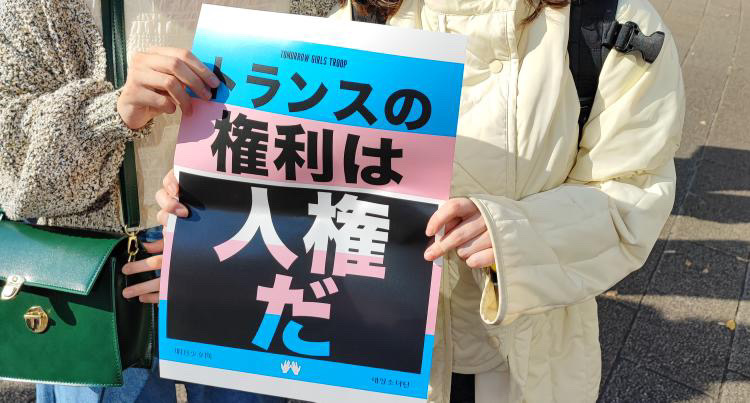

At the same time, transphobic discourses and moral panics have also gained much ground. Following similar trends in other countries, there has been an increase in transphobic fear mongering and even hate speech towards trans people on television, in newspapers and especially on social media. Such fear mongering and misinformation is perhaps not as widespread and persistent as it has become in the United Kingdom or the United States, but it has already led to harassment and even death threats in some cases in Japan. On October 21, a protest of about 20 people was held in Shinjuku chanting slogans such as “protect children!” while holding up signs asking the Supreme Court to refrain from impeding “women’s safety and dignity” in its upcoming ruling. Much of these anti-trans discourses in Japan are focused on trans women in particular and the threat they supposedly pose towards so-called “female spaces”, such as women’s onsen.

How the Court rules could have significant implications for the lives of Japan’s trans population. One potential ruling from the Court could say that demanding sterilization is in violation of Article 13 while on the other hand upholding the constitutionality of the need to have something between your legs resembling the “right genitals” because of the need to prevent “interference with the public welfare”, in line with the fears raised by anti-trans groups. Because the effects of testosterone can bring about changes regarding one’s genitals that satisfy the GID Law’s fifth requirement, people who seek to change their legal gender from male to female would in the vast majority of cases continue to have to undergo bottom surgery, while most people requesting to change from female to male wouldn’t.

The Court may also rule that requiring surgery is completely unconstitutional, and allow the woman who brought the case to change her legal gender. While this would be good news for many trans people in Japan, the other stringent requirements of the law would continue to exist and there would still be no legal gender option to reflect the identities of Japanese citizens with nonbinary gender identities. Furthermore, some trans people in Japan have also expressed fear about the potential backlash such a ruling could bring.

Finally, the Court may also fail to render any part of the law unconstitutional. Such an outcome would certainly be a setback, diminishing the precedent created by the Shizuoka Family Court two weeks earlier. In this scenario, it will almost definitely take at least several years—and probably even longer—before an eventual loosening of the law is achieved. Court cases such as these will likely be advocates’ best bet for achieving important changes on this front so long as the ruling Liberal Democratic Party remains mostly ambivalent about the issue with some members having even joined a recently formed anti-trans parliamentary group. Despite criticism from international organizations such as Human Rights Watch and The World Professional Association for Transgender Health, as well as UN rapporteurs, no one within the LDP seems concerned about the suffering resulting from a law that is increasingly at odds with international norms. Until that changes, the Supreme Court remains the best – and maybe only – option for those seeking change.

Emily Boon is a researcher at the LeidenAsiaCentre. She has a BA Japanese Studies and an MA Asian Studies from Leiden University, and spent a year as an exchange student at Waseda University's Graduate School of Political Science. Her research focuses primarily on Japanese local politics and LGBTQ+ politics.