The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of The Asia Group.

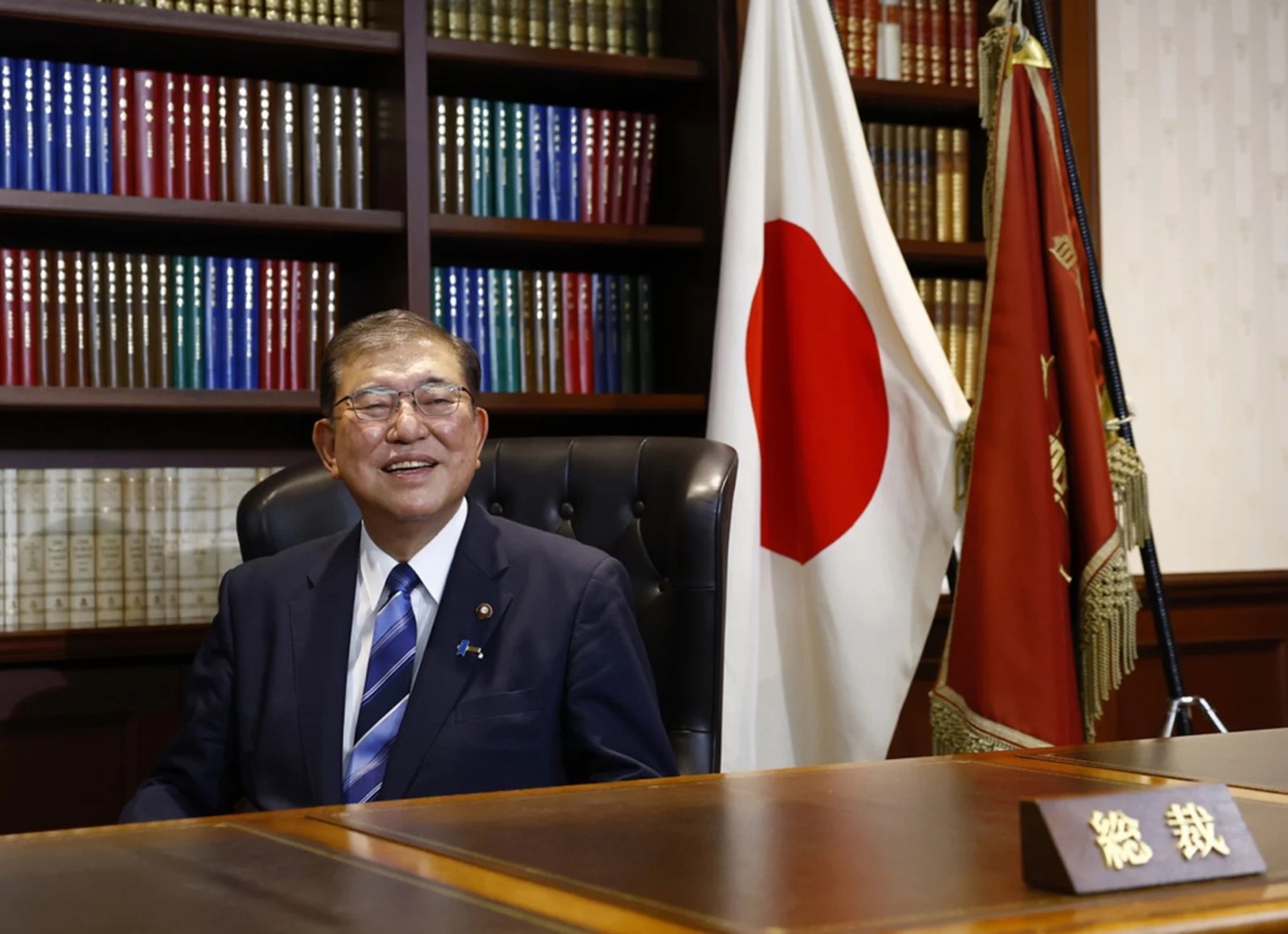

The inauguration of Ishiba Shigeru as the 112th prime minister of Japan signals the end of what can be described as the “Abe era” of Japanese politics — the decades-long dominance by the conservative wing of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Though the influence of the Abe wing of the LDP began to wane long before Ishiba’s election, the ascent of Abe’s rival to the top turns a new leaf in the party’s history, ushering in the replacement of the conservative wing by the moderate liberal wing of the party as the epicenter of power.

However, not all is set in stone for this transition of power, which has been characterized by some as a de facto “change in government.” The presence of Takaichi Sanae, a self-proclaimed Abe successor, coupled with Ishiba’s strategic exclusion of Abe’s friends and political allies, makes for a turbulent transition of power that may threaten to destabilize the LDP’s grip on power.

Ishiba Looks to “Purge” Abe’s Influence

One of the first moves Ishiba made as new LDP president was to systematically exclude Abe’s friends and political allies.

First, he decided not to appoint any Abe faction members in his Cabinet or party leadership (with the exception of Fukuda Tatsuo, a member of the faction who is not a close ally of Abe). This was explained as a reflection of public discontent with the Abe faction, which played a central role in the slush fund scandal that ultimately resulted in former Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s effective ouster.

Ishiba did offer rival presidential candidates Takaichi and former Economic Security Minister Kobayashi Takayuki party leadership positions; however, both likely saw the positions as unworthy of their election performance and declined, instead requesting that their supporters be appointed to senior positions.

Ishiba also took it a step further and decided not to extend endorsements to twelve LDP candidates — mostly former members of the Abe faction — in the upcoming general election. Though the official reasoning was that these candidates were either heavily involved in the slush fund scandal or did not fulfil their responsibility to explain their involvement in said scandal, the abrupt decision and subsequent announcement that the party would deny proportional representation listings (an insurance card for candidates to be ‘resurrected’ if they lose in single member districts) to forty-three candidates led to accusations that Ishiba was using the election to “purge” Abe allies.

Conservatives resent Ishiba, contending that’s he’s a backstabber who unsuccessfully challenged Abe in the 2012 and 2018 presidential elections and continued to criticize the Abe administration, despite serving as party secretary general during the Abe years. They believe that this criticism in turn motivated Ishiba to pursue the elimination of the Abe faction. However, the abrupt decision is thought to have been a choice made by the new party leadership determining that these candidates faced a real possibility of losing their re-election bids.

The perception that he is using the election as a way to achieve personal retribution will stick regardless of Ishiba’s actual intentions. Media reports suggest that the actual decision to not extend endorsements to Abe faction candidates was made by Secretary General Moriyama Hiroshi and Election Strategy HQ Chair Koizumi Shinjiro, while Ishiba himself struggled to determine where to draw the line between candidates to support and those to exclude from party support.

Second, Ishiba was able to both intentionally and unintentionally remove Abe’s key political allies from positions of influence. LDP Vice President Aso Taro, a long-time Abe ally who voted for Takaichi, was stripped of his title and placed in an honorary “senior advisor” role. The veteran former prime minister was regarded as a “kingmaker,” supporting Suga Yoshihide and Kishida Fumio as prime minister following Abe’s resignation in 2020. Ishiba also removed former Executive Secretary to Prime Minister Imai Takaya, Abe’s trusted aide, from his role as special advisor to the Cabinet for energy policy that he continued to hold under the Kishida administration.

One unintentional result from Kishida’s tenure as leader was the retirement of Nikai Toshihiro, the longest-serving party secretary general who held the position under then-President Abe, which effectively removed two of Abe’s most influential political allies.

Party Unity or Popular Support?

The fall of the conservative wing has ushered in the emergence of the more moderate, liberal wing of the party as the central force in party politics. Led by former prime ministers Kishida and Suga, this wing of the party has a different view on the future direction of the party, including on contentious issues for conservatives like same-sex marriage and fiscal policy.

This was initially viewed as a boost for Ishiba, who himself stands in contrast with Abe and the conservative wing on these issues. Ishiba’s popularity with the public in large part stemmed from not being part of the so-called establishment forces, characterized by political corruption and backwardness toward accepting societal change.

Yet, Ishiba has been finding it difficult to implement his policy ideas in the early days of his administration, in large part due to resistance from conservative forces within the party. Ishiba has already toned down his openness to separate surnames for married couples — one of the most talked about issues during the presidential election — stating in the Diet on October 8 that there must be careful deliberation as it is an “issue at the core of how families are structured.” This reflects his desire to avoid unnecessary internal conflict ahead of a general election in which the LDP already facing headwinds due to the political scandal.

While Ishiba will now be supported by moderate liberals who align more closely with his policy ideals than the conservatives, he faces the dilemma of being stuck between managing intra-party dynamics and appeasing the public ahead of a major national election. Though the conservatives are now disjointed without Abe at the helm, they still constitute a critical mass within the party capable of making life difficult for the prime minister. There have been cases in the recent past where conservatives, despite not being a closely knit group, were able to water down policies like the LGBT bill last year in what became a heated debate within the party.

Such resistance, though not strong enough to outright veto Ishiba’s policies, will remain as a reminder that the prime minister will not get his way simply by freezing out conservatives from positions of power.

Rumblings of Discontent

A victory in the upcoming election — deemed to mean that the LDP holds a majority of seats and maintains hold of government — will likely be insufficient to calm voices of discontent with Ishiba.

The existence of Takaichi, a conservative candidate who surprisingly outperformed Ishiba in the first round of the presidential election among local party members, is a sliver of hope for conservative Diet members to regain power in a post-Ishiba LDP. Even though she may not be every conservative member’s desired leader, she is more likely to succeed Abe’s policies and reinstate ousted members into positions of power.

The exclusion of influential political figures like Aso and former Secretary General Motegi Toshimitsu also raises the possibility of a “grand coalition” forming to remove Ishiba from power should the LDP underperform in the upcoming Lower House and Upper House elections to come within the first year of Ishiba’s leadership. Despite having different political positions, the main figures in this hypothetical coalition stand united in their discontent with Ishiba — some for his betrayal of Abe and others for personal grudges going back decades.

Ishiba will need strong electoral performances, much like Abe and Kishida who lasted longer than others, to hold onto power. The new prime minister needs the popular mandate more than other leaders without a strong foundation of power within the party. While Kishida and Suga backed him this time, it was more out of necessity rather than choice. The new “kingmakers” could turn their back on Ishiba in no time if the public turns its back on him.

To make matters worse, Ishiba’s decision to leave a lifeline for the Abe faction candidates — bringing them back to the party should they win re-election as independents — may come to haunt him, as they will return with a vengeance rather than gratitude toward the leader.

The new era of Japanese politics is one of turbulence, as the LDP struggles to leave behind an era dominated by Abe and his uncanny ability to manage relations with powerbrokers leading political factions.

For Ishiba, this is a consequential election not just because it’s his first, but because the results will be an early indicator of longevity as leader and whether he has survived the worst or faces a continued crisis due to opposition from within his party going forward.

Rintaro Nishimura is a Tokyo-based Senior Associate in The Asia Group’s Japan practice, where he researches and analyzes domestic political shifts, economic security, and technology policy developments. He is a co-founder of the U.S.-ROK-Japan Next-Gen Study Group, a platform for young professionals to regularly discuss issues pertaining to the trilateral relationship. He graduated with a MA in Asian Studies (MASIA) at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, focusing his studies on the U.S.-Japan alliance, economic security in the Indo-Pacific, and Japanese domestic politics. He has extensive writing experience, having published in the Georgetown Journal of Asian Affairs, Nikkei Asia, The Interpreter, The Diplomat, The National Interest, Tokyo Review, and Asia Tech Observer. He has also been quoted in BBC, CNN, Reuters, Bloomberg, Nikkei Asia, Voice of America, Al Jazeera, and CNBC. He can be found on Twitter (@RinNishimura) and http://rintaronishimura.com.